As darkness falls upon the night sky, ominous clouds gather, their undersides swirling with a menagerie of grays and blacks. A banner, emblazoned with the proud symbol of a horse's tail, flutters and dances in the breeze as a light drizzle starts to fall. In the distance, low and rumbling thunder can be heard, growing steadily louder with each passing moment. The angry waves of the Aegean Sea crash relentlessly into the rocky shoreline, sending plumes of saltwater high into the air in a majestic display of nature's power. A storm is coming, and it promises to be unlike any other.

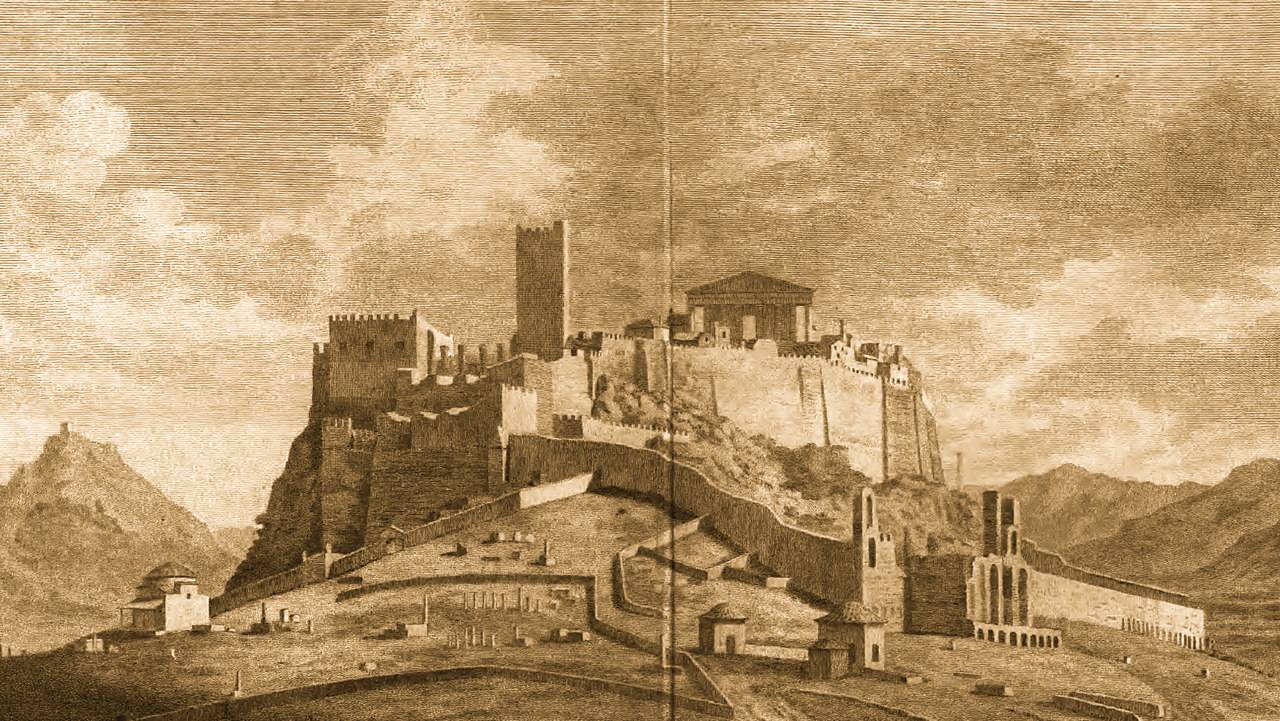

Beneath the banner, a man with powerful figure stands tall and proud, his muscular frame cloaked in a blue tunic adorned with exotic patterns that shimmer in the flickering torchlight. His face, strong and handsome, is a testament to his noble heritage, with prominent features that are highlighted by the dancing flames. His gaze shifts between the churning sea and the cloud-covered sky, finally settling on the blurred shadow of a distant city of Thessaloniki that lies beyond the reach of the torchlight.

"Your Highness," comes a soft voice from behind him, breaking the silence of the night, "the wind is heavy, and the drizzle has dampened your hair. It would be wise to seek shelter from the impending storm."

The young man turns slightly, acknowledging the presence of his grand vizier, Bayezid Pasha, a trusted advisor and friend who has been with him through many trials and tribulations. "I know, my dear friend," he replies, his voice carrying a hint of melancholy that is rare for one so powerful. "But we do not have the luxury to choose the storms of life. We can only endure them and hope to emerge victorious on the other side."

Bayezid nods solemnly, understanding the weight of responsibility that rests upon his Sultan's shoulders. "Your Highness has faced many storms before and has always emerged victorious," he says with conviction in his voice. "This too shall pass, and your reign will continue to prosper."

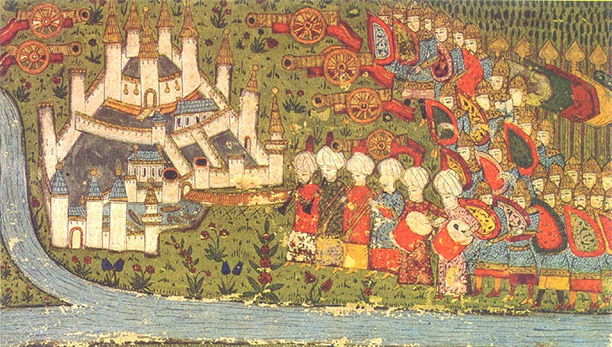

The Sultan turns back to face the sea, his voice hardens and the tiny trace of melancholy disappears with the wind. "Speaking of storms," he begins, "the Venetians have dealt us a heavy blow at Gallipoli, taking many lives and dealing a significant blow to our fleet."

Bayezid frowns, knowing that the loss of their navy at Gallipoli is a serious setback to his Sultan’s new reign. "It is true that we have suffered a setback," he admits, "but the Venetians are not without their own weaknesses. Their fleet may dominate the sea, but they are powerless on land. Their holdings and castles lie bare and open to our arrows and lances. If they choose to challenge us further, they will surely meet their end."

The Sultan nods slightly, his gaze hardening as he considers the future. "Yes, the Venetians may think they have the upper hand now," he says coldly, "but they will soon learn that they have bitten off more than they can chew. Bah, they are but a minor pain… As for my 'dear' cousin Mustafa and that traitor Junayd Bey," he spits the words out with contempt, "they will pay dearly for their treachery."

Bayezid remains silent, he knows the Ottoman crown has weight down on the Sultan. Ever since the disaster at Ankara, where the former Sultan Bayezid the Thunderbolt was captured by the Tamerlane the World Conqueror, the realm of the Ottomans has been tumultuous. The situation only began to stabilize after the ascension of his Sultan to the throne three years ago, yet fortune force his Sultan, the proud Mehmed to ride against challenge after challenge, crisis after crisis, with no end in sight. With a heavy heart, Bayezid turns his attention to the approaching storm, watching as the raindrops grew larger and heavier with each passing moment.

As the storm draws nearer and the rain begins to fall in earnest, the Sultan stand his ground unmoving, allowing the elements to wash over him. It was as if he were trying his will against the challenge of nature. But the Sultan is a man of iron resolve, and he would not be moved.

"When the time comes," after a long silence, the Sultan opens up finally, his voice carrying over the howling wind and crashing waves, "we will strike back at the Venetians with all the force we can muster. And when we do, it will be like a thunderbolt in the night, swift and unexpected. But as of now, we must eliminate the parasite Mustafa, and that wicked man of Bedreddin first and foremost."

Bayezid nods in agreement. The realm faces many threats, compare to the imminent and stubborn disease that is Mustafa and Bedreddin, the Venetians are only a minor discomfort.

The storm rages on around them, but the two men stand firm against the elements, their resolve as strong as ever.

Three days later, a small vessel set sail from the city of Thessaloniki, bound for Constantinople. On board was a messenger carrying a letter

'To my esteemed Basileios,

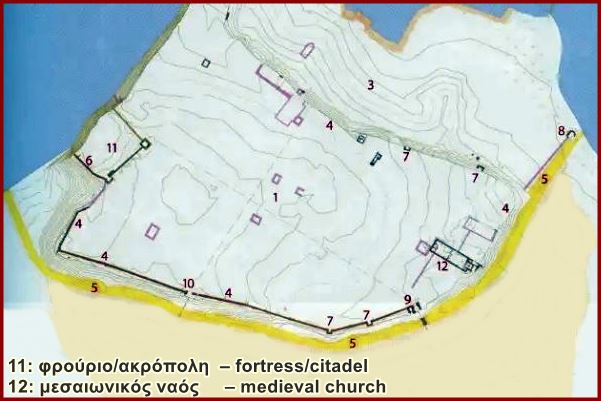

The Ottoman prince, Mustafa, along with the governor of Nicopolis, Junayd Bey, have taken refuge behind the tall walls of Thessaloniki after their humiliating defeat by Sultan Mehmed. The sultan's army pursuits relentlessly and has now encircled our city, demanding their surrender. After three days of delicate negotiations, I have deemed it prudent to apprise my Basileios of the Ottomans' offer through this letter. They propose a sum of one million akces in exchange for the contender to the Ottoman throne .

It is worth noting that during these negotiations, the rebellion in Dobrudja has escalated significantly, to such an extent that it appears to have commandeered Mehmed's complete attention. Despite his illness due to a cold, he abruptly departed with his main force yesterday. Considering the Ottomans' precarious situation, I believe they may be amenable to terms more favorable to us. However, such a negotiation demands a direct line of communication between two heads of state.

Meanwhile, Thessaloniki stands resolute. Our walls are manned by vigilant guards, our people are well-provisioned, and morale is high. The Ottoman navy, having suffered a crippling defeat by the Venetians, is unable to blockade our port. Our city shall endure. Despot Andronikos, having recovered from his recent illness, sends his warm regards to you.

I pray this letter finds my Basileios in good health and high spirits.

Your ever-loyal and devoted servant,

Demetrios Laskaris Leontares'

On the fifth day of June, in the year of our Lord 1416.

Beneath the banner, a man with powerful figure stands tall and proud, his muscular frame cloaked in a blue tunic adorned with exotic patterns that shimmer in the flickering torchlight. His face, strong and handsome, is a testament to his noble heritage, with prominent features that are highlighted by the dancing flames. His gaze shifts between the churning sea and the cloud-covered sky, finally settling on the blurred shadow of a distant city of Thessaloniki that lies beyond the reach of the torchlight.

"Your Highness," comes a soft voice from behind him, breaking the silence of the night, "the wind is heavy, and the drizzle has dampened your hair. It would be wise to seek shelter from the impending storm."

The young man turns slightly, acknowledging the presence of his grand vizier, Bayezid Pasha, a trusted advisor and friend who has been with him through many trials and tribulations. "I know, my dear friend," he replies, his voice carrying a hint of melancholy that is rare for one so powerful. "But we do not have the luxury to choose the storms of life. We can only endure them and hope to emerge victorious on the other side."

Bayezid nods solemnly, understanding the weight of responsibility that rests upon his Sultan's shoulders. "Your Highness has faced many storms before and has always emerged victorious," he says with conviction in his voice. "This too shall pass, and your reign will continue to prosper."

The Sultan turns back to face the sea, his voice hardens and the tiny trace of melancholy disappears with the wind. "Speaking of storms," he begins, "the Venetians have dealt us a heavy blow at Gallipoli, taking many lives and dealing a significant blow to our fleet."

Bayezid frowns, knowing that the loss of their navy at Gallipoli is a serious setback to his Sultan’s new reign. "It is true that we have suffered a setback," he admits, "but the Venetians are not without their own weaknesses. Their fleet may dominate the sea, but they are powerless on land. Their holdings and castles lie bare and open to our arrows and lances. If they choose to challenge us further, they will surely meet their end."

The Sultan nods slightly, his gaze hardening as he considers the future. "Yes, the Venetians may think they have the upper hand now," he says coldly, "but they will soon learn that they have bitten off more than they can chew. Bah, they are but a minor pain… As for my 'dear' cousin Mustafa and that traitor Junayd Bey," he spits the words out with contempt, "they will pay dearly for their treachery."

Bayezid remains silent, he knows the Ottoman crown has weight down on the Sultan. Ever since the disaster at Ankara, where the former Sultan Bayezid the Thunderbolt was captured by the Tamerlane the World Conqueror, the realm of the Ottomans has been tumultuous. The situation only began to stabilize after the ascension of his Sultan to the throne three years ago, yet fortune force his Sultan, the proud Mehmed to ride against challenge after challenge, crisis after crisis, with no end in sight. With a heavy heart, Bayezid turns his attention to the approaching storm, watching as the raindrops grew larger and heavier with each passing moment.

As the storm draws nearer and the rain begins to fall in earnest, the Sultan stand his ground unmoving, allowing the elements to wash over him. It was as if he were trying his will against the challenge of nature. But the Sultan is a man of iron resolve, and he would not be moved.

"When the time comes," after a long silence, the Sultan opens up finally, his voice carrying over the howling wind and crashing waves, "we will strike back at the Venetians with all the force we can muster. And when we do, it will be like a thunderbolt in the night, swift and unexpected. But as of now, we must eliminate the parasite Mustafa, and that wicked man of Bedreddin first and foremost."

Bayezid nods in agreement. The realm faces many threats, compare to the imminent and stubborn disease that is Mustafa and Bedreddin, the Venetians are only a minor discomfort.

The storm rages on around them, but the two men stand firm against the elements, their resolve as strong as ever.

Three days later, a small vessel set sail from the city of Thessaloniki, bound for Constantinople. On board was a messenger carrying a letter

'To my esteemed Basileios,

The Ottoman prince, Mustafa, along with the governor of Nicopolis, Junayd Bey, have taken refuge behind the tall walls of Thessaloniki after their humiliating defeat by Sultan Mehmed. The sultan's army pursuits relentlessly and has now encircled our city, demanding their surrender. After three days of delicate negotiations, I have deemed it prudent to apprise my Basileios of the Ottomans' offer through this letter. They propose a sum of one million akces in exchange for the contender to the Ottoman throne .

It is worth noting that during these negotiations, the rebellion in Dobrudja has escalated significantly, to such an extent that it appears to have commandeered Mehmed's complete attention. Despite his illness due to a cold, he abruptly departed with his main force yesterday. Considering the Ottomans' precarious situation, I believe they may be amenable to terms more favorable to us. However, such a negotiation demands a direct line of communication between two heads of state.

Meanwhile, Thessaloniki stands resolute. Our walls are manned by vigilant guards, our people are well-provisioned, and morale is high. The Ottoman navy, having suffered a crippling defeat by the Venetians, is unable to blockade our port. Our city shall endure. Despot Andronikos, having recovered from his recent illness, sends his warm regards to you.

I pray this letter finds my Basileios in good health and high spirits.

Your ever-loyal and devoted servant,

Demetrios Laskaris Leontares'

On the fifth day of June, in the year of our Lord 1416.

Last edited: