Chapter One: The Shots Heard Round the World

The Shots Heard Round the World

Opening narration from Apocalypse: The Great War, voiced by David Attenborough

Exert from: Invasion of Belgium, an Animated VidHub [2] Documentary

In the decades before the Great War, the Belgian Army had constructed a series of fortifications along its borders with France and Germany. Although the Belgians acknowledged that they would probably not be able to hold off any invasion for long, they also acknowledged the need to prevent the Germans and French from just walking into Belgium in order to outflank the enemy. Countries then, like now, prefer to have their territorial integrity respected.

Although the independence of Belgium had been guaranteed by both nations, the track record of both for respecting treaties when it was not in their interest was not exactly spotless. Both very clearly wanted to kill the other but the fortifications erected on both countries’ borders prevented them from doing that on their own without significant casualties. Switzerland was too mountainous for the timely transportation of troops and that left Belgium as the convenient speed bump between these two speedcars. Building fortifications would also give time for allied forces (chiefly the British) to move into and reinforce Belgium.

On the German-Belgian border, the Belgians constructed a series of modern fortifications. The one directly on the German border, at Liege, had 12 forts on both sides of the river Meuse in a 30 mile radius, along with a citadel constructed around the city itself. These forts were constructed to be impenetrable by all modern artillery, and were manned by 32,000 Belgian troops at the time of war. Leading them was General Leman [3], who was appointed to his post earlier in the year. This led to Liege being considered one of the most heavily fortified spots in all of Europe, and would lead to the Germans and Austrians to develop specialized artillery pieces for the sole purpose of taking Liege. The Austrian Skoda gun had a barrel measuring 12-inches, while the German Krupp (a.k.a. Big Bertha) gun had an even larger barrel of 16.5 inches. The modern fortifications of the day were primarily strengthened by steel-reinforced concrete with earth filled cavities. This required high explosive and high angled artillery shots to destroy. The Krupp and Skoda guns served this exact purpose and allowed for holes to be blown into even the most modern fortifications.

………………

Field Marshall Bulow Second Army would be assigned to take the city of Liege, who promptly handed the task to General Otto von Emmich and 6 brigades numbering 50,000 men to lead the assault on the city. Supporting them was 80 pieces of artillery and a 30,000 man strong cavalry detachment. This so-called “Army of the Meuse” was made of the best units the Germans could muster for the task of taking Liege.

The Germans would need the best troops at their disposal. The Liege was a natural chokepoint for the Germans. To the north was the Dutch border, an obvious no-go unless Germany wanted to go to war with what was intended to be the economy’s lifeline during the British Blockade. To the south was Ardennes Forest, which would limit the ability of the Germans to sustain operations in Belgium and France logistically. Liege was also a railway and transportation hub that would be needed to move and supply the 750 '000 soldiers moving into Belgium. Liege had to be taken.

The Deputy Chief of Staff for the Third Army, one Erich Ludendorff, was attached to the 14th Brigade as an observer. Ludendorff had previously investigated the defenses at Liege, and it was hoped that he would inform the 14th Brigade as it attempted to secure the bridges inside the city before they were destroyed. On the Fifth of August, the commander of the 14th would be killed outside fort, leading to Ludendorff taking command [4]. Ludendorff wouldn’t fare much better, as he would also be shot and killed on the Fifth. With two commanders killed in a single night, the 14th Brigade retreated back to their positions, having made no gains that night.

From Left: Photo of General Erich Ludendorff, killed on August 5th, General Otto von Emmich, commander of the Army of the Meuse, and the Big Bertha Artillery Gun

The guns worked as advertised, cracking open several forts and forcing the garrisons to surrender. This was long and hard work for the Germans however, and they were rightfully fearful that the timetable set forward by the Schlieffen Plan was in danger of being torn to shreds. If Liege itself could not be taken, then the next best course of action would be to cut off the city from reinforcements. On the 12th a 5’000 strong German cavalry force was sent through the Ardennes Forest to encircle Liege. A series of artillery barrages and attacks on the east-facing forts were arranged in hope of drawing Belgian attention away from the south. The plan failed however when civilians spotted the cavalry force and reported it to nearby Fort Boncenes. The news was brought straight to General Leman, who immediately understood the intent of the German flanking maneuver: encirclement. With the eastern fort's perimeter already beginning to break under the full force of the German bombardment, Leman ordered for the forts on the eastern banks of Meuse destroyed and the destruction of all bridges across the Meuse as well as the destruction of all railways running through Liege. It was difficult however for the garrisons to retreat from their forts due to the constant German attack. Surrounded by the German cavalry force, Fort Boncenes would be unable to retreat and would surrender to the Germans on the 15th. An attempt by the three eastern forts not taken or destroyed by the Germans to retreat under cover of darkness on the 13th resulted in a firefight with a German scouting regiment. The skirmish was inconclusive but had the effect of alerting the Germans to the retreat. On the 14th the Germans moved into the interior of the Liege defense perimeter, hot on the heels of the retreating Belgians.

To cover the retreat of forces from Liege proper, civilians were enlisted to create barricades around entrances to the city. This had the effect of either slowing down the German advance or forcing them into kill zones where the Belgians would ambush them from shop corners. Squads armed with nothing more than rifles, machine guns, and grenades were able to hold off regiments of German soldiers for over two days. This marked one of the first instances of modern urban combat during the Great War. The intent was not to repel the German assault, but to delay, a task which the Belgians would excel at here. Entire families would flee with the Belgian army as well, for stories of war crimes inflicted against civilians in the Liege area were spreading. On the 16th, again under cover of darkness, the final Belgian squads left Liege and for good measure blew the bridges across the Meuse. On the 17th the Germans would move into Liege only to find no way across the Meuse, all the rails blown up, and no Belgian soldiers to kill or capture. The Belgian position on the western side of the Meuse would be untenable however as the full weight of German artillery bore down on the Lemans’ forces. Under pressure from King Albert I, Leman finally retreated from the Fortified Position of Liege on the 20th of August, marking the end of the Battle of Liege. Although the Battle of Liege technically ended with a German victory, the German goal of quickly capturing the city failed. The railways and bridges running through Liege were also destroyed, delaying the Germans from moving and supplying large numbers of troops moving in through Belgium. It would be the first of a number of events that would see the failure of the Schlieffen Plan.

Exert from: AP 10th Grade History Book from the United States of America

German forward units committed numerous atrocities against the Belgian populace, believing that terrorizing the Belgian people would cow them into submission. This only served to galvanize the Belgian people in defense of their homes. It also served to hurt Germany’s reputation internationally, as page after page detailing German atrocities were published in the newspapers. Nations lined up to condemn German atrocities, and much of the world's sympathy for Germany dried up. A famous German atrocity was in Louvain, where German soldiers shot and murdered hundreds of Belgian civilians and set fire to the 14th Century University, along with hundreds of medieval manuscripts. The collective war crimes committed against Belgians became known as the Rape of Belgium, and featured heavily in Entente wartime propaganda.

On the battlefront, the German army suffered a series of delays that slowed the advance into France. At Mons the British Army successfully fended off a German attempt to take their positions by blowing up the bridges across the Sambre. Although unsuccessful at completely stopping the German advance, delays such as these gave the Entente time to reinforce themselves and the defenses around Paris. At the Battle of the Marne, the largest land battle on earth up to that point, the German army attempted to take Paris in the culmination of the Schlieffen Plan. A successful French and British counterattack repulsed the German attack and threatened to encircle the German forces. Fearing this, the Germans retreated to positions in Northern France and Belgium and dug in. Upon charging these positions and suffering appalling casualties, the French and British did the same. This began what was known as Trench Warfare.

Trench warfare is characterized by dug in positions fortified by barbed wire. The depth and style of the trenches differed from army to army and place to place. Some German trenches were dug over 9 feet deep and contained many amenities. Other trenches were essentially foxholes connected by shell craters. These trenches were made in a zig zag pattern so you couldn’t shoot across the trench line. These trenches would grow ever more complex as the war dragged on, and would prevent any large movements on the front without a massive cost being placed on the defenders.

In an attempt to outflank the other, the Entente and Central Powers would extend the trench line all the way up north into Belgium. Between the Germans and the English Channel stood the Belgian Army and Antwerp, the provisional capital. The Race to the Sea had begun.

Exert from: The Great War, A History

On September 7th, 1914, Ludendorff’s funeral would be held in the very capital of Germany: Berlin. Ludendorff was not a famous officer by any measure, with his most well known action being that he died in Liege. Regardless, appearances had to be kept up as he was the highest ranking German officer to have been killed in combat up to that point. Many prominent political and military figures in Germany arrived at the funeral service, including Kaiser Wilhelm II, leader of the Social Democratic Party Friedrich Ebert, Chancellor Bethmann-Hollweg, former Chief of Staff von Moltke the Younger, then-Chief of Staff Falkenhyen, future media mogul Alfred Hugenburg, Field Marshall Paul von Hindenburg of Tannenberg fame, and others. One person who was missing was General Otto von Emmich. For his failure to take Liege, Emmich was forced into retirement by the OHL, which held him responsible for prolonging the battle. As a new addition to the nobility as well as being a mid level officer in the military he was the perfect candidate for a scapegoat. His superior Field Marshall Bulow was too well connected to be of any use for that purpose. And so General Otto von Emmich, former commander of the Army of the Meuse was quietly relieved of his duty and sent home. Shortly after, Emmich would die of arteriosclerosis in his native Hanover. At this time the political unity that had swept over Germany near the start of the war was still very much in force, despite the failure of the Schlieffen Plan and Austrian attacks into Serbia. The demonstration of this political unity was regarded with the utmost importance by most politicians in the Reichstag and a funeral for a high ranking officer was just the occasion for that kind of gesture in support of the war. Attendance was not purely political in nature though as it was a genuine expression of solidarity in the political scene. When SPD Deputy Karl Liebknecht publicly questioned Ebert’s attendance in the funeral and why he was “granting his blessings to an enemy of the proletariat such as Ludendorff,” he was expelled from the party and forced into military service on the eastern front, where he would be wounded on the right shoulder from Russian shrapnel. [5]

It was a closed casket ceremony with a procession through Brandenburg Gate before being marched over to a nearby graveyard. Kaiser Wilhelm II gave a speech praising Ludendorff’s military career and ended with a message on the “necessity of sacrifice for the fatherland”. The public was made aware of the event well in advance, and plenty of journalists and newspapers were present for the event to record the events and write down quotes. Recently appointed chief of staff Falkenhyn was present, although he did not give a speech to the funeral procession and contented himself by being one of the pallbearers.

It would be in the funeral that then-Lieutenant Colonel Wilhelm Groener first met Field Marshall Paul von Hindenburg and his Chief of Staff Hoffman [6]. Groener was the head of the OHL Railway section, an ever more important sector as the war consumed more and more resources. It was not the most prestigious of posts but was well respected by most officers in the German Army. Hindenburg had been called out of retirement to deal with the Russian invasion of Prussia after the commander of the Eighth Army, von Prittwitz panicked and called for a retreat and it was understood that a from East Prussia. Prior to arriving in East Prussia, he had been assigned the chief of staff of the Eighth Army Max Hoffman, who masterminded a counterattack against the advancing Russians. A great victory was won against the invading Russians at the famous Battle of Tannenberg, something that would propel Hindenburg to being a nationally loved figure. The battle had actually been fought near the town of Allenstein, but Hoffman had seen the benefit of casting the battle as revenge for the medieval Battle of Tannenberg and renamed it such.

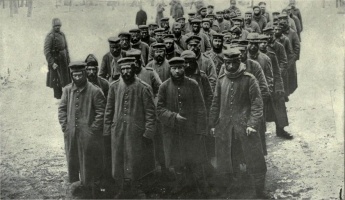

From Left: Leuitenant Colonel Wilhelm Groener, Chief of the Railway Section of the General Staff, General Max Hoffman, Chief of Staff of the German Eighth Army, and General Paul von Hindenburg, Commander of the Eighth Army

__________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

Authors Note: This is my second attempt at a TL. I kind of rushed into my first TL without a plan for what I was doing and made a bunch of mistakes that I do not intend on making now. I've done some research into what I'm trying to do and I have built up a plan on what I intend on doing this TL. If you have a question, comment, or concern for TTL, feel free to post it. Otherwise, I hope you enjoy it. Thank you for your time. I might be slow for a follow up chapter, I'm going to be pretty busy for the next month.

[1] I’m not going to insult your intelligence. We all know how WW1 starts and I feel that it wouldn’t tread on too many toes for me to just speak in generalities here. And yes, that is Sir David Attenborough. I thought it would be fun to have him narrate a WW1 documentary.

[2] TTLs version of Youtube

[3] According to his Wikipedia article, when he was told by a minister that the building up of fortifications along the German border could be construed as an act of aggression against Germany, he reportedly said that it was his job to prevent that, and if the Germans didn’t they could “take away his general stars”

[4] This was an actual event that happened during the OTL Battle of Liege. IOTL he managed to squeeze the 14th Brigade into a gap in the Fortified Position of Liege. This was one of the events that would lead to Ludendorff’s rapid ascent to his position as Hindenburg’s Chief of Staff and later Quartermaster General. It doesn’t turn out too well here though.

[5] During his recovery from his wounding, he would develop an addiction to morphine, kneecapping any potential future political career. Leibknecht did actually serve on the Eastern Front IOTL as a gravedigger. The event which caused this was his voting against the extension of war credits in December 1914. Given that he was willing to pull a stunt like that in December that year, I wouldn’t put it past him to say something like this in September. I do feel kind of bad getting him out of the picture like this.

[6] Do check out his Wikipedia article here, it's pretty interesting. As it turns out it was him that masterminded the victory at Tannenberg, not Ludendorff. Ludendorff and Hindenburg just took all the credit. He was also the guy who gave Tannenberg its name as it turns out.