Was the Hindenburg-Ludendorff "silent dictatorship" of 1917-18 verging on proto-Nazism in terms of programs, prejudices, intentions for postwar order?

I've read vague allegations, mostly without substantive details, but relying on adjectives like "dictatorial", "authoritarian" for describing its politics and "managed" or "command" to describe its economy to hint the silent dictatorship was a stepping stone toward Nazism.

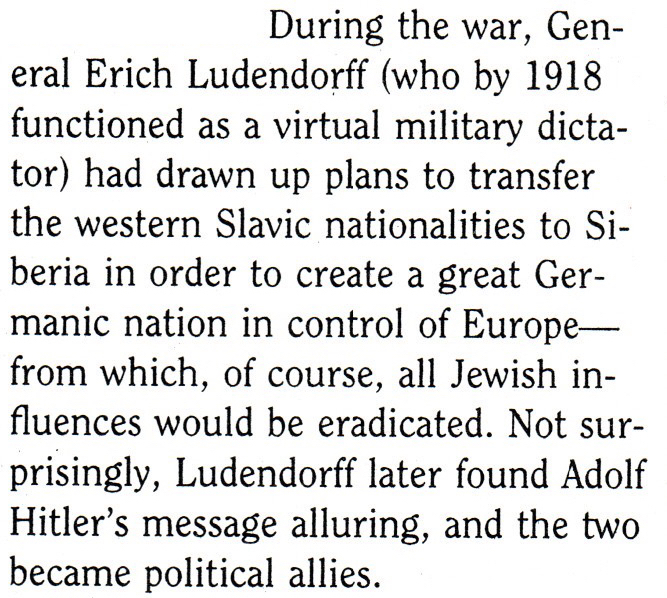

But one historian, Williamson Murray, got a little more specific in an article in Military History Quarterly, saying:

Has anyone else ever seen any account of this type of planning by the WWI German command to deport western Slavs and eradicate Jewish influence one way or the other, a sort of proto-Generalplan Ost and Holocaust? Or was this an author perhaps getting a bit carried away?

The only things I know for sure about Ludendorff is that in wartime he used his bureaucratic command influence to press for maximum munitions production, knocking the economy out of balance, pressed for German imposed victory over negotiated peace (and so grasped at expedients like unrestricted submarine warfare) until nearly the end, when he had a breakdown and told the Kaiser and government they must sue for peace, he belatedly tried to reverse course and argue to keep fighting when he'd convinced everyone to give up hope and the country was on the verge of mutiny and revolution, he fled the country in disguise, and postwar he built up the stab in the back myth, was into fringe right-wing politics, partnered up with Hitler in the Beer Hall putsch, and was personally weirder in his Aryanism-Nordicism than certainly Hindenburg and even the Nazis, openly advocating a German return to paganism, which postwar, kept him a marginal political figure. All the things in this paragraph, I've read in two or more sources, but the idea of racial reengineering of western Russia and anti-semitic action I have only seen in this one place.

Is it attested elsewhere? Would Ludendorff have really tried to press such a program, in the event, somehow, of late German victory after Ludendorff was in a key leading position? Would he have had any chance of carrying it through or would such plans have broken down due to resistance elite and grassroots political forces and logistical impracticalities?

I've read vague allegations, mostly without substantive details, but relying on adjectives like "dictatorial", "authoritarian" for describing its politics and "managed" or "command" to describe its economy to hint the silent dictatorship was a stepping stone toward Nazism.

But one historian, Williamson Murray, got a little more specific in an article in Military History Quarterly, saying:

Has anyone else ever seen any account of this type of planning by the WWI German command to deport western Slavs and eradicate Jewish influence one way or the other, a sort of proto-Generalplan Ost and Holocaust? Or was this an author perhaps getting a bit carried away?

The only things I know for sure about Ludendorff is that in wartime he used his bureaucratic command influence to press for maximum munitions production, knocking the economy out of balance, pressed for German imposed victory over negotiated peace (and so grasped at expedients like unrestricted submarine warfare) until nearly the end, when he had a breakdown and told the Kaiser and government they must sue for peace, he belatedly tried to reverse course and argue to keep fighting when he'd convinced everyone to give up hope and the country was on the verge of mutiny and revolution, he fled the country in disguise, and postwar he built up the stab in the back myth, was into fringe right-wing politics, partnered up with Hitler in the Beer Hall putsch, and was personally weirder in his Aryanism-Nordicism than certainly Hindenburg and even the Nazis, openly advocating a German return to paganism, which postwar, kept him a marginal political figure. All the things in this paragraph, I've read in two or more sources, but the idea of racial reengineering of western Russia and anti-semitic action I have only seen in this one place.

Is it attested elsewhere? Would Ludendorff have really tried to press such a program, in the event, somehow, of late German victory after Ludendorff was in a key leading position? Would he have had any chance of carrying it through or would such plans have broken down due to resistance elite and grassroots political forces and logistical impracticalities?