Chapter 1: To Light a Fire under Her

"We will wrap the whole world in flames! No power is so remote that she will not feel the fire of our battle and not be burned by our conflagration!" United States Secretary of State William H. Seward as overheard at a diplomatic function by William H. Russell in 1862 during the Trent Crisis.

“So bloody was the march of the revolution, and the impression which it made was the greater as it was one of the first to occur. Later on, one may say, the whole Hellenic world was convulsed; struggles being every, where made by the popular chiefs to bring in the Athenians, and by the oligarchs to introduce the Lacedaemonians. In peace there would have been neither the pretext nor the wish to make such an invitation; but in war, with an alliance always at the command of either faction for the hurt of their adversaries and their own corresponding advantage, opportunities for bringing in the foreigner were never wanting to the revolutionary parties.” - Thucydides, The Peloponnesian War, Chapter X

“The great conflict which erupted across the North American continent in 1861 has gone on to have many names; the Southern Rebellion, the War of Northern Aggression, the War of 1862, the American Civil War, but perhaps the most common name agreed on by all English scholars since Arthur Chambers in his 1919 essay “The Great American War” is the namesake of the essay. Certainly comparisons have been drawn to the great conflict of the later 20th century, and many British observers were equally tempted to liken the conflict waged across North America to the wars against the French from 1792-1815. Perhaps a grandiose comparison, but in terms of the scale of the conflict, the men involved and the cost in blood and treasure, it is not wholly inaccurate.

The war was without a doubt a defining moment in the history of the English speaking world. It has often been said that the 1860s were a decade on which the ideologies of a new age were hammered out upon the anvil of war, certainly an idea which the scholars of the New Men at a later time would happily agree with. The war and its aftermath divided and united nations, forged new alliances, and very much gave rise to the North America and its nations which we know today.

For the beginning of the war itself, few Americans need a lesson on what would divide a nation. The ‘peculiar institution’ of the South had long divided peoples of the industrializing North and the agrarian South. The Founding Fathers unable to find compromise on the matter and assured of its swift demise in a few generations time felt comfortable enough to leave the issue to a perhaps more enlightened generation. Little could they have predicted the sudden surge in the profitability of servile labor with the introduction of the cotton gin. The internal slave trade exploded and the expansion of slavery was seen as an economic necessity by the South. The more abolitionist North, with its increasing industrialization and view of the new territories of the Union as a haven for individual farmers and land owners saw this as anathema to their own view of the nation. The question though, would again be passed down to what it was hoped would be another more enlightened generation. Half-hearted compromise would again be initiated come 1850, but by that time it was too late. The sectional divides over the issue of the right to human bondage were too great, and a mere ten years later one of the most contentious elections in the history of the United States would lead to the division of the nation.

The United States as it existed on the eve of war in 1860 was a prosperous nation, one of the greatest industrial nations in the world, yet still just on the cusp of the powerhouse it would come to be at the dawn of the 20th century, having only a third the manufacturing power of Great Britain. Though not considered as such, the United States of the 19th century was still a power in earnest, not the least challenged in its sphere of influence for a period of well over half a century. It had expanded uninterrupted across the face of the North American continent unchecked save by the British lands in the North and an aversion to the absorption of the more populous Catholic peoples to the south. Indeed with such successful expansion the call of Manifest Destiny and the ‘Union from the Arctic Circle to the Caribbean’ seemed like it would in time be a simple self-fulfilling prophecy, as the preponderance of evidence as to the superiority of American institutions would assert itself upon the peoples of the continent.

The course of history though, as it so often does, would frustrate this prophecy.

As it was, on the eve of war the only true threat to the Union was either from enemies internal, or from those across the Atlantic, namely the great maritime empires of France and Britain. France having few toeholds in the New World was not seen as an imminent danger to the Union. Britain however, was always seen as a potential enemy. However, it seemed at the time the simple realities of economics would overcome such feeling. Indeed despite lingering memories of the 1775-83 conflict and the more recent conflict of 1812-1815 the two nations were each other’s greatest trading partners. Raw American goods (primarily cotton) were exchanged for British capital and machine tools, all of which bankrolled the continuing industrialization of the United States.

This of course was to the primary benefit of the North however, with the expanding industries of New England and the Midwest. The South remained largely an agrarian land of expansive slave plantations and yeoman farmers, with little industry to its name, instead relying on machine tools and cheap manufactured goods from the North to whet its appetite.

Perhaps to better illustrate this point it is best to examine the vast disparity of resources between the states that would form the Southern Confederacy in 1861 and those that would stay with the Union in 1861. In terms of population the North had roughly 22 million inhabitants, of that only 400,000 were enslaved, exclusively in the border states. In the South there were some 9 million inhabitants, 5.6 million free and 3.5 million enslaved. The Union had over 100,000 manufacturing establishments to the South’s mere 18,000. The entirety of the South produced only 36,000 of the 820,000 tons of the nation’s pig iron and only some 900,000 of the 15,000,000 tons of coal produced nationally in 1860.

All of this was subject to change and expansion as the two sides began to mobilize the resources available to them, and the North of course had much greater depth to draw upon.

These comparisons do discount the importance of both foreign capital and resources to the war effort however. The South pinned much of its hopes on the importance of the cotton trade to Europe, with cotton comprising over two thirds of the exports of the United States this did not seem a farfetched goal to many in the South, with the claim that with no cotton “England would topple headlong and carry the whole civilized world with her, save the South.” And to many this rather over the top prediction did not seem completely outside of reality, with many English merchants worrying in 1861 that millions would starve as the mills of the north west shut down and thousands would go on to government relief. On the other side the loss of American trade would be a punishing blow for British exports, with American trade composing one of the largest markets in the British sphere.

However, it cannot be understated how important British goods were to the Union war effort. For instance, in 1860 the United States consumed some 1,216,000 tons of iron in its industrial expansion, yet domestically only produced some 821,000 tons. The remaining 395,000 tons were imported from abroad, including some 122,000 tons of railroad iron. This all mainly came from Britain, which produced some 3.5 million tons of iron in 1860. The United States produced less than 8,000 tons of steel, while Britain produced over 40,000 tons, and the United States had yet to construct a single Bessemer converter. The United States produced 15 million tons of coal in 1860 while in the same year Britain produced over 70 million tons. Most importantly for the war effort perhaps was the production of saltpeter. Prior to the war the United States had enough domestic industry to produce gunpowder for its own needs, but imported the vast majority of its powder from abroad, and the main supplier was Britain with its near monopoly on quality nitre from India. These items were all imported in some quantity in peace time, and on the outbreak of war these imports would nearly double. In terms of sheer industrial power the British Empire far outstripped its American competitor in the 1860s, and when the Union was divided the North’s 21 million inhabitants were outnumbered by the 29 million inhabitants of the United Kingdom, the 3 million British subjects of the North American provinces notwithstanding.

This is not to assume though, that each nation was prepared to go to war with the other. However, both sides nursed a mistrust of the others intentions. The United States resented the British encroachment on her sovereignty when she insisted she had the right to search all ships which might be taking part in the banned African slave trade, and certainly felt chagrined at Britain’s assumption it could simply interdict and challenge trade as it did in the Napoleonic and Crimean Wars. In return Britain nursed old grudges from American support of rebels along the border in the Rebellions of 1837-38, the war mongering over the Oregon Territory and Maine Boundary Dispute, and the perceived favoritism of Russia in the Crimean War when the United States had recalled her Minister to the Court of St. James. However, the election of volatile personalities to the top positions of power in the 1860s on both sides of the Atlantic would merely add to the healthy suspicion each side favored one another with…” To Arms!: The Great American War, Sheldon Foote, University of Boston 1999.

"To put the world in order, we must first put the nation in order; to put the nation in order, we must put the family in order…” – Confucius

“…when on the 1st of October Albert was riding alone in his carriage in Coburg tragedy struck. On his way to a meeting the carriage, drawn by four horses, bolted with sudden alarm. The driver attempted to reign them in to no avail. The carriage struck the rear of another at a railway crossing in a terrific crash. The driver fell into the seething mass of braying horseflesh but managed to escape relatively unharmed. The Prince Consort was not so lucky.

It is believed that due to the pain from stomach cramps his attempt to jump clear ended with him tumbling from a sudden cramp which meant he fell into the worst possible position as upon impact the carriage crashed and flipped sending Albert hurtling from his seat. He landed two feet away at an unfortunate angle breaking an arm and suffering a serious head wound which rendered him unconscious. He failed to awake an hour later, and at 9pm he was pronounced dead.

Victoria immediately went into grieving, and all of Britain joined her…” A Biography of the House of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha, Nigel Loring, Oxford University, 2011

In raiding and plundering be like fire – Sun Tsu

“On the morning of October 10th 1861 three men checked themselves into a local hotel in St. Albans Vermont. They claimed they were from Saint John’s in Canada (East) and had come to Vermont to have a ‘hunting trip’ which was not unusual for men of middling wealth as they appeared to be. However over the next week they rarely left the hotel and were steadily joined by nineteen more men. Finally the group struck on the morning of the 19th of October.

The men proclaimed themselves to be in service to the government of the Confederate States of America and acting under orders to collect funds for the war effort.

They acted quickly, rounding up the villagers at gun point. Several tried to resist as shouted orders to assemble and Confederate proclamations were called. Two men were killed, one wounded, and a woman injured in the crossfire but the Confederates seized the town with little difficulty. Nine men held the villagers while the others separated the bank tellers and forced them to open the vaults of the three banks in town. Before they did this they were compelled to swear allegiance to the Confederate States of America, therefore making them accomplices to the robbery (or so the raiders claimed). That done they managed to seize a total of 209,000$ from the three banks, all of the towns horses and over two dozen bottles of liquor. Before they left they tossed incendiary devices at three buildings but these failed to ignite and only burnt down one shed while badly damaging one homes porch.

The men rode like hell for the border and pursuit was not joined for over six hours allowing a clean escape.

These raiders, not being mere bandits, were actually a band of some twenty five Confederate soldiers selected for special service along the British North American frontier. Commissioned by the government in Richmond to “set a fire along the border” with the intent of both pulling Union forces away from the war to the South, and by violating British neutrality they hoped to pull Great Britain into the internecine warfare raging through the United States. It was hoped this would both alleviate the pressure on the Confederacy while also securing foreign recognition thus achieving a fait accompli in diplomatic negotiations with the other nations of the world and thereby dealing fatal blow to Union diplomacy.

The men were led by the daring Confederate cavalry commander John Hunt Morgan, and organized into a quick raiding force meant to cause terror and panic while wreaking havoc behind Union lines. Here he also hoped to steal enough money to fund further campaigns

The raiders next struck six days later, raiding Franklin Vermont on the 23rd in a morning raid seizing the bank teller while starting several fires to distract the townsfolk. They made off with a further 45,000$ but suffered one killed in a gun fight with armed townsfolk. They again escaped across the border. This time though they were closely pursued by a militia posse.

However, the raiders had split into two groups at this point. The other, under the energetic young lieutenant Bennet H. Young, had split off to deposit their winnings while the others were to lead the posse to the nearest Canadian settlement then disperse. The first thing they found however was a Canadian militia patrol which arrested them immediately. The militia met up with their Americans counterparts who began demanding immediate custody of the fugitives, while the Canadians refused, insisting they be tried in local courts. There was a tense standoff over the next hour while the two sides negotiated.

There was a reluctant agreement and the American militia returned home to inform their government of these events. Meanwhile Young and his men were captured in St. John in an ironic turn of events, and soon all the raiders were held there awaiting trial…” A History of Special Forces, James Rawles, University of Moscow, 2001

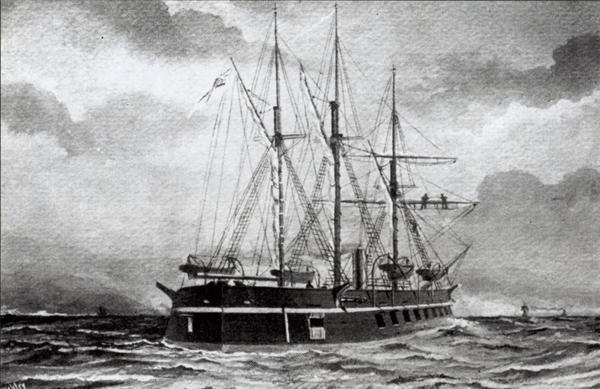

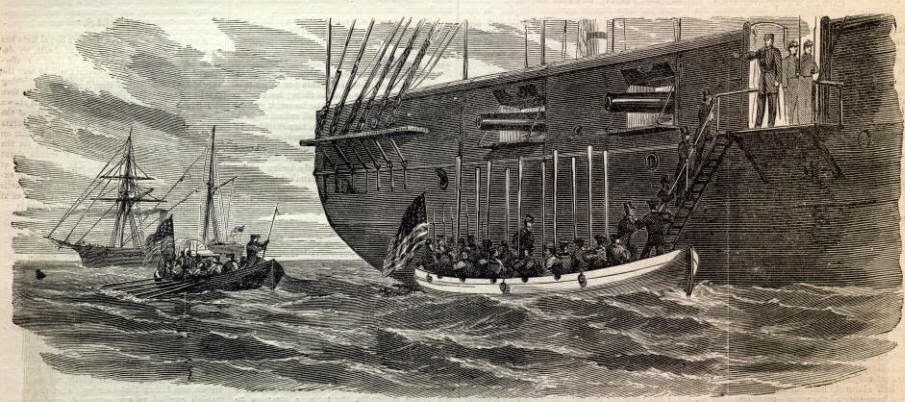

…Aboard the deck of the USS San Jacinto Wilkes held an impromptu prize court. This was not unusual of Wilkes’s brash and aggressive style of command. It had often been said that had a reputation as a stubborn, overzealous, impulsive, and sometimes insubordinate officer, with Treasury Officer George Harrington writing so Seward saying: "He will give us trouble. He has a superabundance of self-esteem and a deficiency of judgment. When he commanded his great exploring mission he court-martialed nearly all his officers; he alone was right, everybody else was wrong." So the quick and abrupt nature of his decision was not unusual and he needed to make the best of a potentially bad situation. He announced his intention to take stop the Trent and search her for contraband, and seize any Confederates he found aboard. Amazingly none of his officers disagreed with his decision and he proceeded to steam alongside the Trent and fired a warning shot. The Trent had the Union Jack raised high and at first ignored the shot. The second shot however was something which could not be safely ignored and she slowed to allow herself to communicate with a launch party from the San Jacinto…

…almost immediately Lieutenant Fairfax ran into trouble. The crew and passengers of the ship were belligerent and when he announced his intention to seize the ship as a prize a fight broke out between two of the crew and his marines. Though it was quelled almost immediately the passengers proved utterly unwilling to cooperate with Fairfax’s instructions and did everything they could to hamper the search of the ship. Finally events came to a head when Richard Williams (a Royal Navy officer in charge of the ships dispatches) bluntly refused to allow the Confederate envoys bags to be searched after being caught attempting to hide them. Although it is unclear what happened it is known a fight ensued between Williams and Fairfax which ended in Williams shot dead. Since only Williams, Fairfax and two marine escorts were present at the time of the altercation the truth of the matter will almost certainly never be known, however all present asserted that Fairfax shot in self-defence after Williams verbally lashed out and Fairfax shouted back, events after are somewhat confused however with one claim that Williams assaulted Fairfax and another that it was an accident assumed in self-defence. The news of the death spread quickly and the remaining passengers and crew settled into reluctant compliance as the commissioners were hauled from the boat and the Trent again set adrift in an uncertain sea…” A History of Diplomatic Blunders, Friedrich Kaufmann, Imperial University, Moscow, 1969