Thanks! Glad you like the TLYou're doing an amazing job !

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Darkness before Dawn - Purple Phoenix 1416

- Thread starter elerosse

- Start date

Threadmarks

View all 19 threadmarks

Reader mode

Reader mode

Recent threadmarks

CHAPTER 11 – SUPER GRAMMATICAM CHAPTER 12 – A MENACE IN THE FORESTS CHAPTER 13 – UNSCRIPTED DEVELOPMENT CHAPTER 14 – A FINE CATCH AT ACROCORINTH CHAPTER 15 – A FORCEFUL MEDIATION MAP of 1418 CHAPTER 16 – A CITY REBORN CHAPTER 17 – A HERETIC PRINCEAlways up for the byzantines surviving!Thanks! Glad you like the TL

CHAPTER 8 – BAPTISM BY FIRE

CHAPTER 8 – BAPTISM BY FIRE

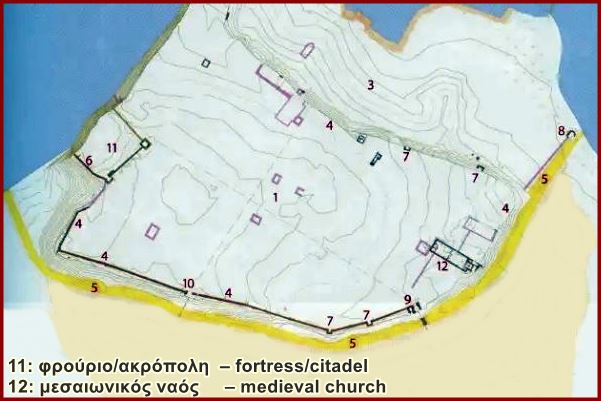

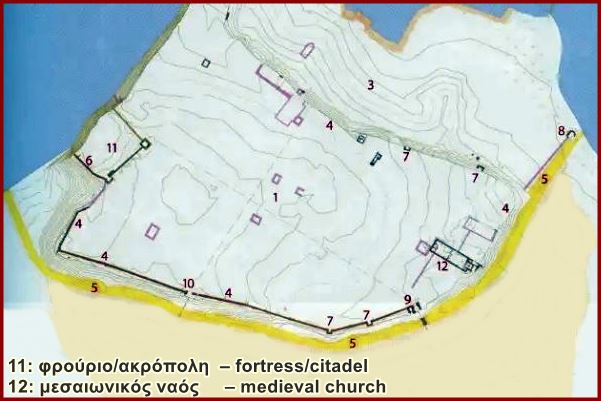

- The Layout of Glarentza Castle

- Ruins of modern day Glarentza Castle, seeing from the eastern side

*******************************************************************

Andronikos surveys the muddy ground outside his camp, the result of several days of relentless rain. Wooden walkways have been laid to facilitate the soldiers' movements, connecting the tents and camps of the ever-expanding Imperial encampment that surrounds the castle of Glarentza.

With heavy thoughts weighing on his mind, Andronikos wraps himself in a cloak and strides towards the main camp for a war council. Eighteen days have passed since their arrival in Achaea, and ten since the siege of Glarentza commenced.

However, the situation has been deteriorating, as the weather has taken a turn for the worse. Sporadic but persistent early spring rain has turned the ground into a muddy quagmire, hampering efforts to set up camp, prepare siege equipment, and fill the moats surrounding the walls. A seasoned commander knows the toll such relentless rain takes on the men's health and morale. The defensive posture of Glarentza offers little comfort to the Romans as well.

Glarentza, founded in the mid-13th century by William II of Villehardouin, the first Latin prince of Achaea, stands as the principal port and mint of the Frankish Principality. Nestled on a small plateau, sloping gently from west to east, it occupies a strategic position at the northwestern tip of the Chelonatas peninsula in the Elis region. Its irregular shape spans approximately 450 meters from east to west and 350 meters from north to south, encompassing an area of roughly 8,800 square meters. The town's northern and western sides border the sea, guarded by a sheer cliff that plunges fifty meters into the waves. The port, situated in the north, is sheltered from the harsh western and southwestern winds. While Glarentza's walls may not compare to the grandeur of Constantinople or Thessaloniki, breaching them remains a laborious task due to the town's advantageous defensive terrain. This fact was immediately apparent to Andronikos upon his arrival, as he recognized the daunting challenges his men faced—Roman soldiers must haul their equipment and siege engines up a slippery slope before encountering a long moat. Only after filling the moat under enemy fire can they approach a series of ramparts, and only after demolishing these can they draw near the walls themselves.

The Latins, despite being outnumbered, have sufficient manpower to fully garrison every inch of Glarentza's fortifications. As the main port and bastion of Latin influence in the Peleponnese, Glarentza is home to two thousand inhabitants, a mix of merchants, urbanites, craftsmen, and professional soldiers. Andronikos has no doubt that Centurione has mobilized every able-bodied man for his cause. The young prince faces a tough and unforgiving struggle ahead.

Stepping into the tent, Andronikos is immediately overwhelmed by the tense atmosphere of the ongoing war council. He watches as Leontares and Theodoros intently discuss a spread-out map, their brows furrowed as they seemingly ponder the strategic layout for the next move.

Ioannes, standing across the table, notices Andronikos' arrival and gives him a subtle nod of acknowledgment. With a firm voice, he declares, "So far, despite some hindrances from the weather, our campaign has been progressing smoothly. In less than a month, we have successfully encircled Centurione and his Latin accomplices in Glarentza, and we have secured almost all of Achaea under imperial control. It's only a matter of time before all of Achaea is reunited under the Empire!"

"Glory to the Empire!" the men present shout in unison, their voices thundering.

Ioannes' eyes glint with confidence as he continues, "Now, Glarentza stands as the final barrier before us. We must seize the momentum and launch a fierce attack! Strike the enemy hard! Our siege engines must be ready within two weeks. By then, reinforcements from Morea will have arrived, and we shall capture Glarentza once and for all!"

However, not everyone shares Ioannes' optimism. Leontares voices his concerns cautiously, "My lord, I understand your eagerness, but Glarentza has been fortified by the Latins. They possess many experienced siege warriors. I've heard rumors that they have even mounted two cannons on their walls. We must not underestimate the enemy."

"Cannons? Hah, they are mere toys that only scare cowards! They are useless in real warfare!" scoffs Demetrios Koutsoukos, a veteran and old-school general from Constantinople, he is trusted by Ioannes.

Ioannes concurs with Demetrios and scoffs, "Leontares, you worry too much sometimes. The Latins in Glarentza are isolated, with no reinforcements coming to their aid. Once we attack, they will panic and lose their will to fight."

However, Leontares stands his ground, "The Latins are renowned for their tenacity. I have faced them in the past, and they will not surrender easily. I am not opposed to attacking, but we must prepare thoroughly, especially against arrows and firearms. Every soldier of the Empire is a precious asset. We cannot afford to sacrifice their lives in hasty assaults."

Andronikos comes to Leontares' aid, agreeing, "Leontares is right. We can make additional preparations while still adhering to the timeline set by you, my lord."

Ioannes' expression briefly turns serious, but he soon recognizes the validity of Leontares' concerns. "Extra preparations can indeed be beneficial - as long as everyone meets the deadline. But ensure that your soldiers get adequate rest before the attack. I don't want a tired army that lacks focus due to lack of sleep."

Leontares and Andronikos nod in agreement. After further discussion, it is decided that the attack will commence on mid April. However, before the operation, Leontares proposes a strategy, "We could initiate a probing attack to assess the enemy's weak points. This way, we can launch a more targeted assault during the official attack."

The men nod in unison, acknowledging the wisdom of Leontares' suggestion. Thus, a carefully planned siege operation is about to unfold.

Days later, the Roman army begins its probing attacks to assess the enemy's strength and defensive setup. It quickly becomes obvious that the steep hill posed a serious challenge to the attacking army. While soldiers were climbing up hill, they get showered by a consistent arrow fire. Despite their bravery, the Roman soldiers have their shields pierced repeatedly by arrows, and their armor is being marked with mottled scars. The probing attack shows that without proper preparation, it would be very difficult to storm and take the castle.

The weather finally turned dry before the assault, seen by many as a blessing from God. The men are no longer hindered by muddy terrain, providing a significant relief to the Romans.

On a cloudy morning 15 April 1417, with a light breeze whispering through the air, the Roman forces march out of their camp in an organized manner. The front line is composed of men wielding large shields and specially constructed wagons with wooden planks in front. Following closely behind them are men carrying sacks filled with sand and dirt. Their mission is to fill the moat, shielded by the men with shields and wagons.

Next in line stands approximately a thousand armored men armed with spears and bows, most of them hailing from Thessaloniki. The spearmen's task is to guard against any potential enemy assault, while the archers provide covering fire.

The drums of war echo across the battlefield, and purple banners wave, signaling the commencement of the attack.

Hundreds of men stride across the treacherous hillside, their hearts pounding as they draw nearer to the moat in the distance. The enemy in Glarentza waits patiently, their weapons at the ready, holding their fire until the Romans enter their range.

Andronikos, mounted on his steed, watches anxiously as the first line of wagons rumbles towards the moat. Suddenly, a deafening roar erupts from the walls of Glarentza, and a cannonball crashes into the ground near a wagon, sending a shower of dirt and sand into the air.

"So that is the power of cannon," Andronikos gasps, his heart racing with excitement and fear as he beholds the devastating weaponry he has never witnessed in action before.

"Yes, the Venetians have them mounted in their galleys – they are invaluable in siege warfare and naval battles," Leontares replies, his voice steady despite the chaos. "They may lack precision, but their impact is devastating."

The Thessaloniki soldiers, tasked with protecting the wings of the army, move in formation behind the wagons and dirt-bearers, always on the alert for enemy assaults. They are new to battle, and their nerves are on edge, but they steel themselves, determined to carry out their duty.

'Bang!' Another round of cannon fire shatters the air, and Andronikos watches in horror as a cannonball lands a direct hit on a wooden wagon. The wagon explodes into shards of wood, sending a hail of flying debris that kills and wounds a dozen men around it.

The battlefield is a cacophony of screams, shouts, and the constant bangs of cannon fire. Men duck and weave, trying to avoid the hail of arrows and cannonballs. The air is filled with the acrid smoke of gunpowder, and the ground is littered with debris and bodies.

As the men near the moat, the arrows start to rain down upon them. Most are intercepted by shields and wagons, but some slip through the defenses, landing hits on unarmored men. The screams of the wounded and dying echo across the battlefield, adding to the horror of the scene.

By noon, despite the constant barrage of cannonballs and arrows, the Roman men work furiously to fill the moat. Their arms are aching, their backs are broken, but they persevere, driven by their desire to conquer.

"Get the first column of men back for rest, send in the second column!" general Demetrios shouts, his voice hoarse from shouting orders. He senses that his men are tiring, and he knows that they need to rotate to keep up the pace.

As the first column of shield-men and dirt-bearers begins to withdraw, the southern gate of Glarentza suddenly swings open. A charge of 200 Latin knights, mounted on tall horses and clad in shining armor, thunders through the gate, lances lowered and eyes blazing with battle fever.

"Epilektoi! Spears down!!" Leontares shouts, his voice a roar above the din of battle. The Thessaloniki forces, positioned on the flanks, face the charging knights directly.

Most of the men follow the drill, forming a tight line with spears lowered. But some, overwhelmed by the terrifying charge, fail to execute the standard procedure. Their movements become jerky, their formation shatters.

"May God help them," Leontares whispers, his heart heavy as he watches the Latin knights charge into the disarrayed groups, slicing through the fleeing men like butter.

But the men who have formed a solid formation manage to stall the advance of the main charge, holding the knights back with a wall of spears. The Latin charge is disrupted, breaking into a stalling main group and a smaller group pursuing the broken formations.

Sensing an opportunity, Leontares quickly decides to lead his cavalry out to intercept the smaller group, leaving Andronikos with the main formation to fend off the main group of Latin knights.

"Archers, fire freely into the enemy!" Andronikos shouts, riding directly behind the ranks. "Men, hold your line!!"

The arrows fly from the Roman bows, piercing the air towards the enemy. The Latin knights has regrouped from their last failed charge, and begins another charge onward, undeterred by the hail of arrows. Their lances glint in the sun as they lower them in preparation for the impact.

The clash of spears and lances is deafening as the two forces collide once more. The Romans hold their line, bracing the impact of the charge with their spears. The Latin knights are forced to slow their advance, but they continue to push forward, determined to break through the Roman defense.

Andronikos watches the battle unfold with a mixture of fear and excitement. He has never seen such violence and chaos before, but he knows that he must steel himself and face it. He urges his men to hold their line, shouting words of encouragement and inspiration.

Months of drills and harsh discipline have paid off on the battlefield. Despite the constant attempts to disrupt their formation, the Latin knights have failed to gain ground. In fact, they have suffered horrendously in the process, with many falling to the spears and arrows of the Romans.

The unstoppable charge that the Latin knights were so proud of has been stopped by a group of trained commoners. The Romans have shown that they are not to be trifled with, and they are determined to conquer Glarentza.

On the other side of the battlefield, Leontares and his cavalry have surrounded the disorganized groups of Latin knights. They attack with precision and ruthlessness, destroying each and every one of them without mercy. The battle is slowly turning in favor of the Romans.

But just as it seems that the Romans have gained the upper hand, the cannons in Glarentza roar once more. This time, they are aimed directly at the Roman formations. Several barrages are fired at the fighting men, most of them hitting the ground nearby and missing their targets.

But one cannonball hits the ground and bounces, striking a Roman soldier and glancing off his shield. It continues its trajectory, hitting the horse beneath Andronikos. The impact shatters the horse's limbs, and Andronikos is thrown off, his body slamming heavily on the ground.

The world spins around him as he lies there, dazed and disoriented. He feels a sharp pain in his leg, and he looks down to see a shrapnel has pierced through his armor, blood streaming down his leg. His heart pounds in his chest as he struggles to get up, but his body feels heavy and unresponsive.

Around him, the battle continues unabated. He hears the shouts and screams of men, the clang of weapons, and the roar of cannons. He tries to focus his mind, to ignore the pain and fear that are washing over him. He knows that he has to get up, he has to fight.

With a groan, he manages to push himself up onto his elbows. His leg is throbbing with pain, but he ignores it and focuses on the task ahead. He looks around for a weapon, seeing a spear lying nearby where he fell. With a grunt, he reaches out and grasps the handle, pulling the spear towards him.

As he stands up by leaning to his spear, wincing against the pain in his leg, he sees the battle unfolding before him. His Epilektoi are fighting valiantly, but the enemy is still strong. With a roar of defiance, he limps towards the Latin knights fighting in front, spear raised and ready for battle. He knows that this is his moment, his chance to prove himself on the battlefield.

Andronikos closes in and thrust his spear against an armored knight, landing a hit on the knight’s helmet. As Andronikos tries once more with a thrust, he sees the Latin knights slowly retreating, Leontares has returned with reinforcement.

After a sigh of relief, a wave of dizziness suddenly hit Andronikos, and he closes his eyes, fading to darkness.

- The Layout of Glarentza Castle

- Ruins of modern day Glarentza Castle, seeing from the eastern side

*******************************************************************

Andronikos surveys the muddy ground outside his camp, the result of several days of relentless rain. Wooden walkways have been laid to facilitate the soldiers' movements, connecting the tents and camps of the ever-expanding Imperial encampment that surrounds the castle of Glarentza.

With heavy thoughts weighing on his mind, Andronikos wraps himself in a cloak and strides towards the main camp for a war council. Eighteen days have passed since their arrival in Achaea, and ten since the siege of Glarentza commenced.

However, the situation has been deteriorating, as the weather has taken a turn for the worse. Sporadic but persistent early spring rain has turned the ground into a muddy quagmire, hampering efforts to set up camp, prepare siege equipment, and fill the moats surrounding the walls. A seasoned commander knows the toll such relentless rain takes on the men's health and morale. The defensive posture of Glarentza offers little comfort to the Romans as well.

Glarentza, founded in the mid-13th century by William II of Villehardouin, the first Latin prince of Achaea, stands as the principal port and mint of the Frankish Principality. Nestled on a small plateau, sloping gently from west to east, it occupies a strategic position at the northwestern tip of the Chelonatas peninsula in the Elis region. Its irregular shape spans approximately 450 meters from east to west and 350 meters from north to south, encompassing an area of roughly 8,800 square meters. The town's northern and western sides border the sea, guarded by a sheer cliff that plunges fifty meters into the waves. The port, situated in the north, is sheltered from the harsh western and southwestern winds. While Glarentza's walls may not compare to the grandeur of Constantinople or Thessaloniki, breaching them remains a laborious task due to the town's advantageous defensive terrain. This fact was immediately apparent to Andronikos upon his arrival, as he recognized the daunting challenges his men faced—Roman soldiers must haul their equipment and siege engines up a slippery slope before encountering a long moat. Only after filling the moat under enemy fire can they approach a series of ramparts, and only after demolishing these can they draw near the walls themselves.

The Latins, despite being outnumbered, have sufficient manpower to fully garrison every inch of Glarentza's fortifications. As the main port and bastion of Latin influence in the Peleponnese, Glarentza is home to two thousand inhabitants, a mix of merchants, urbanites, craftsmen, and professional soldiers. Andronikos has no doubt that Centurione has mobilized every able-bodied man for his cause. The young prince faces a tough and unforgiving struggle ahead.

Stepping into the tent, Andronikos is immediately overwhelmed by the tense atmosphere of the ongoing war council. He watches as Leontares and Theodoros intently discuss a spread-out map, their brows furrowed as they seemingly ponder the strategic layout for the next move.

Ioannes, standing across the table, notices Andronikos' arrival and gives him a subtle nod of acknowledgment. With a firm voice, he declares, "So far, despite some hindrances from the weather, our campaign has been progressing smoothly. In less than a month, we have successfully encircled Centurione and his Latin accomplices in Glarentza, and we have secured almost all of Achaea under imperial control. It's only a matter of time before all of Achaea is reunited under the Empire!"

"Glory to the Empire!" the men present shout in unison, their voices thundering.

Ioannes' eyes glint with confidence as he continues, "Now, Glarentza stands as the final barrier before us. We must seize the momentum and launch a fierce attack! Strike the enemy hard! Our siege engines must be ready within two weeks. By then, reinforcements from Morea will have arrived, and we shall capture Glarentza once and for all!"

However, not everyone shares Ioannes' optimism. Leontares voices his concerns cautiously, "My lord, I understand your eagerness, but Glarentza has been fortified by the Latins. They possess many experienced siege warriors. I've heard rumors that they have even mounted two cannons on their walls. We must not underestimate the enemy."

"Cannons? Hah, they are mere toys that only scare cowards! They are useless in real warfare!" scoffs Demetrios Koutsoukos, a veteran and old-school general from Constantinople, he is trusted by Ioannes.

Ioannes concurs with Demetrios and scoffs, "Leontares, you worry too much sometimes. The Latins in Glarentza are isolated, with no reinforcements coming to their aid. Once we attack, they will panic and lose their will to fight."

However, Leontares stands his ground, "The Latins are renowned for their tenacity. I have faced them in the past, and they will not surrender easily. I am not opposed to attacking, but we must prepare thoroughly, especially against arrows and firearms. Every soldier of the Empire is a precious asset. We cannot afford to sacrifice their lives in hasty assaults."

Andronikos comes to Leontares' aid, agreeing, "Leontares is right. We can make additional preparations while still adhering to the timeline set by you, my lord."

Ioannes' expression briefly turns serious, but he soon recognizes the validity of Leontares' concerns. "Extra preparations can indeed be beneficial - as long as everyone meets the deadline. But ensure that your soldiers get adequate rest before the attack. I don't want a tired army that lacks focus due to lack of sleep."

Leontares and Andronikos nod in agreement. After further discussion, it is decided that the attack will commence on mid April. However, before the operation, Leontares proposes a strategy, "We could initiate a probing attack to assess the enemy's weak points. This way, we can launch a more targeted assault during the official attack."

The men nod in unison, acknowledging the wisdom of Leontares' suggestion. Thus, a carefully planned siege operation is about to unfold.

Days later, the Roman army begins its probing attacks to assess the enemy's strength and defensive setup. It quickly becomes obvious that the steep hill posed a serious challenge to the attacking army. While soldiers were climbing up hill, they get showered by a consistent arrow fire. Despite their bravery, the Roman soldiers have their shields pierced repeatedly by arrows, and their armor is being marked with mottled scars. The probing attack shows that without proper preparation, it would be very difficult to storm and take the castle.

The weather finally turned dry before the assault, seen by many as a blessing from God. The men are no longer hindered by muddy terrain, providing a significant relief to the Romans.

On a cloudy morning 15 April 1417, with a light breeze whispering through the air, the Roman forces march out of their camp in an organized manner. The front line is composed of men wielding large shields and specially constructed wagons with wooden planks in front. Following closely behind them are men carrying sacks filled with sand and dirt. Their mission is to fill the moat, shielded by the men with shields and wagons.

Next in line stands approximately a thousand armored men armed with spears and bows, most of them hailing from Thessaloniki. The spearmen's task is to guard against any potential enemy assault, while the archers provide covering fire.

The drums of war echo across the battlefield, and purple banners wave, signaling the commencement of the attack.

Hundreds of men stride across the treacherous hillside, their hearts pounding as they draw nearer to the moat in the distance. The enemy in Glarentza waits patiently, their weapons at the ready, holding their fire until the Romans enter their range.

Andronikos, mounted on his steed, watches anxiously as the first line of wagons rumbles towards the moat. Suddenly, a deafening roar erupts from the walls of Glarentza, and a cannonball crashes into the ground near a wagon, sending a shower of dirt and sand into the air.

"So that is the power of cannon," Andronikos gasps, his heart racing with excitement and fear as he beholds the devastating weaponry he has never witnessed in action before.

"Yes, the Venetians have them mounted in their galleys – they are invaluable in siege warfare and naval battles," Leontares replies, his voice steady despite the chaos. "They may lack precision, but their impact is devastating."

The Thessaloniki soldiers, tasked with protecting the wings of the army, move in formation behind the wagons and dirt-bearers, always on the alert for enemy assaults. They are new to battle, and their nerves are on edge, but they steel themselves, determined to carry out their duty.

'Bang!' Another round of cannon fire shatters the air, and Andronikos watches in horror as a cannonball lands a direct hit on a wooden wagon. The wagon explodes into shards of wood, sending a hail of flying debris that kills and wounds a dozen men around it.

The battlefield is a cacophony of screams, shouts, and the constant bangs of cannon fire. Men duck and weave, trying to avoid the hail of arrows and cannonballs. The air is filled with the acrid smoke of gunpowder, and the ground is littered with debris and bodies.

As the men near the moat, the arrows start to rain down upon them. Most are intercepted by shields and wagons, but some slip through the defenses, landing hits on unarmored men. The screams of the wounded and dying echo across the battlefield, adding to the horror of the scene.

By noon, despite the constant barrage of cannonballs and arrows, the Roman men work furiously to fill the moat. Their arms are aching, their backs are broken, but they persevere, driven by their desire to conquer.

"Get the first column of men back for rest, send in the second column!" general Demetrios shouts, his voice hoarse from shouting orders. He senses that his men are tiring, and he knows that they need to rotate to keep up the pace.

As the first column of shield-men and dirt-bearers begins to withdraw, the southern gate of Glarentza suddenly swings open. A charge of 200 Latin knights, mounted on tall horses and clad in shining armor, thunders through the gate, lances lowered and eyes blazing with battle fever.

"Epilektoi! Spears down!!" Leontares shouts, his voice a roar above the din of battle. The Thessaloniki forces, positioned on the flanks, face the charging knights directly.

Most of the men follow the drill, forming a tight line with spears lowered. But some, overwhelmed by the terrifying charge, fail to execute the standard procedure. Their movements become jerky, their formation shatters.

"May God help them," Leontares whispers, his heart heavy as he watches the Latin knights charge into the disarrayed groups, slicing through the fleeing men like butter.

But the men who have formed a solid formation manage to stall the advance of the main charge, holding the knights back with a wall of spears. The Latin charge is disrupted, breaking into a stalling main group and a smaller group pursuing the broken formations.

Sensing an opportunity, Leontares quickly decides to lead his cavalry out to intercept the smaller group, leaving Andronikos with the main formation to fend off the main group of Latin knights.

"Archers, fire freely into the enemy!" Andronikos shouts, riding directly behind the ranks. "Men, hold your line!!"

The arrows fly from the Roman bows, piercing the air towards the enemy. The Latin knights has regrouped from their last failed charge, and begins another charge onward, undeterred by the hail of arrows. Their lances glint in the sun as they lower them in preparation for the impact.

The clash of spears and lances is deafening as the two forces collide once more. The Romans hold their line, bracing the impact of the charge with their spears. The Latin knights are forced to slow their advance, but they continue to push forward, determined to break through the Roman defense.

Andronikos watches the battle unfold with a mixture of fear and excitement. He has never seen such violence and chaos before, but he knows that he must steel himself and face it. He urges his men to hold their line, shouting words of encouragement and inspiration.

Months of drills and harsh discipline have paid off on the battlefield. Despite the constant attempts to disrupt their formation, the Latin knights have failed to gain ground. In fact, they have suffered horrendously in the process, with many falling to the spears and arrows of the Romans.

The unstoppable charge that the Latin knights were so proud of has been stopped by a group of trained commoners. The Romans have shown that they are not to be trifled with, and they are determined to conquer Glarentza.

On the other side of the battlefield, Leontares and his cavalry have surrounded the disorganized groups of Latin knights. They attack with precision and ruthlessness, destroying each and every one of them without mercy. The battle is slowly turning in favor of the Romans.

But just as it seems that the Romans have gained the upper hand, the cannons in Glarentza roar once more. This time, they are aimed directly at the Roman formations. Several barrages are fired at the fighting men, most of them hitting the ground nearby and missing their targets.

But one cannonball hits the ground and bounces, striking a Roman soldier and glancing off his shield. It continues its trajectory, hitting the horse beneath Andronikos. The impact shatters the horse's limbs, and Andronikos is thrown off, his body slamming heavily on the ground.

The world spins around him as he lies there, dazed and disoriented. He feels a sharp pain in his leg, and he looks down to see a shrapnel has pierced through his armor, blood streaming down his leg. His heart pounds in his chest as he struggles to get up, but his body feels heavy and unresponsive.

Around him, the battle continues unabated. He hears the shouts and screams of men, the clang of weapons, and the roar of cannons. He tries to focus his mind, to ignore the pain and fear that are washing over him. He knows that he has to get up, he has to fight.

With a groan, he manages to push himself up onto his elbows. His leg is throbbing with pain, but he ignores it and focuses on the task ahead. He looks around for a weapon, seeing a spear lying nearby where he fell. With a grunt, he reaches out and grasps the handle, pulling the spear towards him.

As he stands up by leaning to his spear, wincing against the pain in his leg, he sees the battle unfolding before him. His Epilektoi are fighting valiantly, but the enemy is still strong. With a roar of defiance, he limps towards the Latin knights fighting in front, spear raised and ready for battle. He knows that this is his moment, his chance to prove himself on the battlefield.

Andronikos closes in and thrust his spear against an armored knight, landing a hit on the knight’s helmet. As Andronikos tries once more with a thrust, he sees the Latin knights slowly retreating, Leontares has returned with reinforcement.

After a sigh of relief, a wave of dizziness suddenly hit Andronikos, and he closes his eyes, fading to darkness.

Good chapter, nice battle between the Romans and Latins, both sides have proven to be fierce opponents. Hopefully nothing truly debilitating has happened to Andronikos. Keep up the good work 👍👍👍

CHAPTER 9 – CRACKS FROM WITHIN

CHAPTER 9 – CRACKS FROM WITHIN

- A depiction of Sappings from the Siege of Godesberg 1583, where the attackers digged a tunnel under the besieged castle, detonated it to collapse the walls on top, a common and effective siege tactic during the Medieval and Early Modern period.

************************************************

Andronikos slowly opens his eyes to find himself lying on his bed inside the tent. As consciousness returns, he feels aches all over his body, particularly a sharp pain in his left thigh. He shifts his position slightly to ease the discomfort. An elderly man notices his movement, places a bowl of herbal medicine beside him, and approaches.

"My dear Despot, you've been saved by the grace of God. It's truly remarkable that you've recovered so well. The wound on your thigh is healing nicely," the elder says with a reassuring smile.

Andronikos's head still feels heavy, and he's confused. "What happened? Did we win the battle?" he asks.

"It's been three days since the clash, Despot. Our men bravely repelled the Latin attack, but their cannons prevented us from capturing the castle. Sadly, the Latin flag still flies proudly above its walls," the elder explains.

Andronikos sighs, feeling a mix of relief for his survival and disappointment for not seizing Glarentza. For the next few weeks, he's confined to his tent, receiving guests while patiently waiting for his thigh to heal.

Meanwhile, the siege of Glarentza stalls. Unable to neutralize the enemy cannons, the Roman leadership hesitates to sacrifice their precious soldiers for minimal progress. They face a choice: find a way to silence the cannons, accept unacceptable casualties, or starve the enemy into submission.

The Romans choose the latter course.

As Andronikos gradually recovers, the Romans wait patiently in their camp, watching their supplies dwindle. They hope to outlast the defenders before their own resources run out.

A month passes, and when Andronikos finally attends his first war council since his injury, he's warmly greeted by all. They praise his bravery and sacrifice.

After everyone settles in, Co-emperor Ioannes clears his throat and begins the meeting. "I've called this war council due to our dire situation. The enemy remains entrenched within their walls, while the morale of our soldiers wanes. In the past weeks, I've received increasing reports of drunkenness, brawls, and disobedience. The situation will only worsen, and soon, our fighting spirit and discipline will be lost in this dull and purposeless waiting. If that happens, our men won't survive another enemy cavalry charge."

"The consequences will be catastrophic for our campaign! I will not allow it!" Ioannes slams his fist on the table. He scans the room and his gaze settles on Leontares.

"Tell them your plan, Leontares," he orders.

Leontares stands up as Ioannes sits down. "As you wish, Excellency. We face a critical situation, my friends. Our discipline must be restored before it's too late. Therefore, I propose sending out special inspection squads and military judges around the camp to mediate conflicts and punish anyone who violates martial law."

"Regarding the siege of Glarentza, we cannot rely solely on the enemy's hunger. We must take action and actively harass them, make them struggle, and put extra pressure on their minds and supplies. Fake assaults, sapping efforts, loud noises at night—anything to keep our men busy and the enemy on edge."

"The ground beneath the castle is made of hard and solid gravel, so sapping efforts will take a very long time. But if we disguise our progress and make it appear that we're making steady gains each day, it will undoubtedly create panic and fear among the enemy ranks."

Strategos Demetrios raises his doubts. "My dear Strategos, how do we deal with the enemy cannons that will wreak havoc on our sappers?" he asks.

Andronikos jumps into the discussion. "By building this," he says, placing a model of a small wooden palisade on the table. "Our mathematicians have calculated the range and impact width of the cannons to determine their approximate power. If we fill bags with sand and place them on top of movable wooden palisades, they will cushion the impact and safely protect our sappers."

It's clear that Ioannes, Leontares, and Andronikos have planned this in advance. With no objections, the Romans tries yet another way to take Glarentza.

*************************

Outside the walls of Glarentza, life is nothing short of dire, yet even within its fortifications, the situation offers little comfort. Everything from bread to the merest drop of water is strictly rationed, and the walls are constantly manned, never free from vigilance. The constant harassment and distractions of the Roman besiegers place an immense strain on the nerves of Latin defenders, who are constantly on edge.

In order to maintain morale among his troops, Centurione II Zaccaria showers his knights and men-at-arms with lavish gifts and promises of future rewards. He vows to double their fiefs once the Romans are repelled, a promise that provides a small boost to the morale. As for the representative of the Giustianiani family, who controls over the vital port of Glarentza and whom Centurione had to cede control to during his first war with Theodoros the Despot of Morea in 1408 in exchange for monetary assistance, he offers assurances of expanded trade rights once the conflict is resolved.

The failure of the Romans' initial assault provided a brief respite for the defenders, giving Centurione a renewed sense of hope that they might hold out. The weeks following the assault were relatively calm, until a novel development bring urgent news to Centurione from the guards on the watchtower.

"Milord, you must see this yourself," the guard exclaimed, his voice filled with urgency.

Centurione ascends the watchtower and beholds a startling sight. The Romans have established four camps in close proximity to the ditches, which have been filled during the initial assault. Large canvases shield the camps from the sun and direct observation from the walls of Glarentza. However, the constant movement of laborers entering and exiting the camps provide a revealing sign of their purpose.

Centurione observs the camps closely, noting that the laborers entering carry digging tools and equipment, while those exiting have heavy bags on their backs. During one such trip, a laborer stumbles and fall, spilling the contents of his bag to the ground. To Centurione's astonishment, the bag contains nothing but sand and dirt.

"This is impossible!" he exclaims. As a veteran of warfare, Centurione immediately recognizes the Romans' intention: to dig a tunnel beneath the earth and towards and sap the walls of Glarentza. What puzzles him, however, was that Glarentza is situated on layers of hard gravel, which would render such a feat all but impossible in most cases.

"Prepare the cannons!" he orders, his voice stern and determined.

Soon, the two cannons roar to life, firing upon the Roman camps. However, to the dismay of the defenders, the cannonballs fall short of their mark. The Romans have learned the range of the cannons during their initial assault and have positioned their camps accordingly.

As Centurione fumes over the ineffectiveness of his cannons, the trade representative of the Giustiniani family appears on the watchtower. "My good lord Centurione, I have heard rumors that the Greeks have begun sapping. Is it true?" he inquires.

"It's merely a ruse," Centurione replies. "The ground beneath us is full of gravel. It would be folly for them to continue digging. They will soon exhaust their manpower and resources, all for nothing." He attempts to reassure the representative, who is skilled in the art of business negotiation but knows little of warfare. The representative, though looking skeptical, is forced to accept Centurione's words as truth.

For the next several weeks, all eyes on the walls of Glarentza were fixed on the Roman camps. As the days pass and more dirt and sand were carried out, the mood among the defenders grows increasingly tense. Meanwhile, the Latins attempt various strategies to disrupt the Romans' progress, including feigned attacks, cannon fire, and cavalry charges. However, all their efforts prove fruitless, leaving only more wounded and demoralized soldiers in their wake.

The veterans know what the Romans' success in digging their way to the walls would mean: the collapse of the fortifications and an overwhelming attack by the enemy. Desperately, the Latins attempt to dig their own tunnel to counter the Romans' sapping efforts. But to their dismay, the ground surrounding their castle is indeed composed of gravel, rendering their efforts fruitless.

"How can the Greeks possibly continue to dig through gravel? It makes no sense!" Centurione exclaims, frustration evident in his voice. He watches as a massive mound of dirt grows next to the Roman camps, a testament to their remarkable progress over the past three weeks.

"Perhaps they have found a path through the gravel?" the representative suggests, his voice calm and collected.

"It's impossible. It must be some kind of trick!" Centurione refuses to believe what he was seeing. He turns to the representative, speaking as calmly as he could manage: "We will hold this castle. The Greeks will not prevail in Glarentza. Remember, if the barbaric Greeks take Glarentza, they will revoke all trade privileges granted to the Giustinianis. Privileges that I have personally secured for you."

"Of course, my lord," the representative replies, bowing courtly before leaving the walls. As he descends, one of his servants approaches and whispers in his ear: "A small boat has arrived in the harbor during the night. A messenger requests to see you."

The representative nods slightly, his mind turning over the new information. It appears a new possibility has arisen, and he knows he would have to act swiftly and decisively to protect his and the family’s interests.

On the very next day, as Centurione finishes his morning routine with a prayer in the chapel and walks outside, he is suddenly confronted by a dozen of his knights, all clad in armor. Guessing that they have come to petition for a frontal attack, Centurione walks towards them with a smile: “I appreciate your valor…”

“Lord Centurione, we have come to petition…”

“I know, I know, but you must be…”

“For a negotiated surrender.”

“Patient. ……What?”

Centurione is in shock, he couldn’t believe what he just heard. The knights surround him, then opens a small pathway, and the representative suddenly appears and walks straight to Centurione with a faint smile.

“My lord, I know you have fought valiantly, which I admire. Unfortunately, the situation has become untenable. The Greeks… The Romans have completed their sapping, and they can blow up our walls any minutes, and slaughter us all effortlessly. Fortunately, the Romans send their proposal for surrender yesterday, and it is indeed a generous one: If we surrender now, the Romans will spare our lives, we can keep all our weapons, and all belongings which can be moved by foot. The Roman will in addition carry us into the realm of Count Tocco. We therefore strongly urge you to accept such offer of peace.”

“YOU… Traitors!” the veins of Centurione are all exposed by the anger, his face glowing red. He reaches for his sword in subconscious, but finds the left side of his belt empty. He then remembers he left his sword at the gate of the chapel.

“Traitor, what harsh words my lord. But you see, you misunderstands us, we, all of us, only wishes to safeguard your security. None of us wants to see you perish in a hopeless fight.”

Centurione looks around, and to his despair only sees faces cold as stone. He knows all is lost, his men have decided to surrender, and there is nothing he could do.

“Alas, I give my consent.”

“Wise choice my Lord. Tell the Romans that we accept their terms and surrender.”

On 28 May 1417, a sunny morning, the last holding of the County of Achaea, the mighty castle of Glarentza surrender to the Romans.

- A depiction of Sappings from the Siege of Godesberg 1583, where the attackers digged a tunnel under the besieged castle, detonated it to collapse the walls on top, a common and effective siege tactic during the Medieval and Early Modern period.

************************************************

Andronikos slowly opens his eyes to find himself lying on his bed inside the tent. As consciousness returns, he feels aches all over his body, particularly a sharp pain in his left thigh. He shifts his position slightly to ease the discomfort. An elderly man notices his movement, places a bowl of herbal medicine beside him, and approaches.

"My dear Despot, you've been saved by the grace of God. It's truly remarkable that you've recovered so well. The wound on your thigh is healing nicely," the elder says with a reassuring smile.

Andronikos's head still feels heavy, and he's confused. "What happened? Did we win the battle?" he asks.

"It's been three days since the clash, Despot. Our men bravely repelled the Latin attack, but their cannons prevented us from capturing the castle. Sadly, the Latin flag still flies proudly above its walls," the elder explains.

Andronikos sighs, feeling a mix of relief for his survival and disappointment for not seizing Glarentza. For the next few weeks, he's confined to his tent, receiving guests while patiently waiting for his thigh to heal.

Meanwhile, the siege of Glarentza stalls. Unable to neutralize the enemy cannons, the Roman leadership hesitates to sacrifice their precious soldiers for minimal progress. They face a choice: find a way to silence the cannons, accept unacceptable casualties, or starve the enemy into submission.

The Romans choose the latter course.

As Andronikos gradually recovers, the Romans wait patiently in their camp, watching their supplies dwindle. They hope to outlast the defenders before their own resources run out.

A month passes, and when Andronikos finally attends his first war council since his injury, he's warmly greeted by all. They praise his bravery and sacrifice.

After everyone settles in, Co-emperor Ioannes clears his throat and begins the meeting. "I've called this war council due to our dire situation. The enemy remains entrenched within their walls, while the morale of our soldiers wanes. In the past weeks, I've received increasing reports of drunkenness, brawls, and disobedience. The situation will only worsen, and soon, our fighting spirit and discipline will be lost in this dull and purposeless waiting. If that happens, our men won't survive another enemy cavalry charge."

"The consequences will be catastrophic for our campaign! I will not allow it!" Ioannes slams his fist on the table. He scans the room and his gaze settles on Leontares.

"Tell them your plan, Leontares," he orders.

Leontares stands up as Ioannes sits down. "As you wish, Excellency. We face a critical situation, my friends. Our discipline must be restored before it's too late. Therefore, I propose sending out special inspection squads and military judges around the camp to mediate conflicts and punish anyone who violates martial law."

"Regarding the siege of Glarentza, we cannot rely solely on the enemy's hunger. We must take action and actively harass them, make them struggle, and put extra pressure on their minds and supplies. Fake assaults, sapping efforts, loud noises at night—anything to keep our men busy and the enemy on edge."

"The ground beneath the castle is made of hard and solid gravel, so sapping efforts will take a very long time. But if we disguise our progress and make it appear that we're making steady gains each day, it will undoubtedly create panic and fear among the enemy ranks."

Strategos Demetrios raises his doubts. "My dear Strategos, how do we deal with the enemy cannons that will wreak havoc on our sappers?" he asks.

Andronikos jumps into the discussion. "By building this," he says, placing a model of a small wooden palisade on the table. "Our mathematicians have calculated the range and impact width of the cannons to determine their approximate power. If we fill bags with sand and place them on top of movable wooden palisades, they will cushion the impact and safely protect our sappers."

It's clear that Ioannes, Leontares, and Andronikos have planned this in advance. With no objections, the Romans tries yet another way to take Glarentza.

*************************

Outside the walls of Glarentza, life is nothing short of dire, yet even within its fortifications, the situation offers little comfort. Everything from bread to the merest drop of water is strictly rationed, and the walls are constantly manned, never free from vigilance. The constant harassment and distractions of the Roman besiegers place an immense strain on the nerves of Latin defenders, who are constantly on edge.

In order to maintain morale among his troops, Centurione II Zaccaria showers his knights and men-at-arms with lavish gifts and promises of future rewards. He vows to double their fiefs once the Romans are repelled, a promise that provides a small boost to the morale. As for the representative of the Giustianiani family, who controls over the vital port of Glarentza and whom Centurione had to cede control to during his first war with Theodoros the Despot of Morea in 1408 in exchange for monetary assistance, he offers assurances of expanded trade rights once the conflict is resolved.

The failure of the Romans' initial assault provided a brief respite for the defenders, giving Centurione a renewed sense of hope that they might hold out. The weeks following the assault were relatively calm, until a novel development bring urgent news to Centurione from the guards on the watchtower.

"Milord, you must see this yourself," the guard exclaimed, his voice filled with urgency.

Centurione ascends the watchtower and beholds a startling sight. The Romans have established four camps in close proximity to the ditches, which have been filled during the initial assault. Large canvases shield the camps from the sun and direct observation from the walls of Glarentza. However, the constant movement of laborers entering and exiting the camps provide a revealing sign of their purpose.

Centurione observs the camps closely, noting that the laborers entering carry digging tools and equipment, while those exiting have heavy bags on their backs. During one such trip, a laborer stumbles and fall, spilling the contents of his bag to the ground. To Centurione's astonishment, the bag contains nothing but sand and dirt.

"This is impossible!" he exclaims. As a veteran of warfare, Centurione immediately recognizes the Romans' intention: to dig a tunnel beneath the earth and towards and sap the walls of Glarentza. What puzzles him, however, was that Glarentza is situated on layers of hard gravel, which would render such a feat all but impossible in most cases.

"Prepare the cannons!" he orders, his voice stern and determined.

Soon, the two cannons roar to life, firing upon the Roman camps. However, to the dismay of the defenders, the cannonballs fall short of their mark. The Romans have learned the range of the cannons during their initial assault and have positioned their camps accordingly.

As Centurione fumes over the ineffectiveness of his cannons, the trade representative of the Giustiniani family appears on the watchtower. "My good lord Centurione, I have heard rumors that the Greeks have begun sapping. Is it true?" he inquires.

"It's merely a ruse," Centurione replies. "The ground beneath us is full of gravel. It would be folly for them to continue digging. They will soon exhaust their manpower and resources, all for nothing." He attempts to reassure the representative, who is skilled in the art of business negotiation but knows little of warfare. The representative, though looking skeptical, is forced to accept Centurione's words as truth.

For the next several weeks, all eyes on the walls of Glarentza were fixed on the Roman camps. As the days pass and more dirt and sand were carried out, the mood among the defenders grows increasingly tense. Meanwhile, the Latins attempt various strategies to disrupt the Romans' progress, including feigned attacks, cannon fire, and cavalry charges. However, all their efforts prove fruitless, leaving only more wounded and demoralized soldiers in their wake.

The veterans know what the Romans' success in digging their way to the walls would mean: the collapse of the fortifications and an overwhelming attack by the enemy. Desperately, the Latins attempt to dig their own tunnel to counter the Romans' sapping efforts. But to their dismay, the ground surrounding their castle is indeed composed of gravel, rendering their efforts fruitless.

"How can the Greeks possibly continue to dig through gravel? It makes no sense!" Centurione exclaims, frustration evident in his voice. He watches as a massive mound of dirt grows next to the Roman camps, a testament to their remarkable progress over the past three weeks.

"Perhaps they have found a path through the gravel?" the representative suggests, his voice calm and collected.

"It's impossible. It must be some kind of trick!" Centurione refuses to believe what he was seeing. He turns to the representative, speaking as calmly as he could manage: "We will hold this castle. The Greeks will not prevail in Glarentza. Remember, if the barbaric Greeks take Glarentza, they will revoke all trade privileges granted to the Giustinianis. Privileges that I have personally secured for you."

"Of course, my lord," the representative replies, bowing courtly before leaving the walls. As he descends, one of his servants approaches and whispers in his ear: "A small boat has arrived in the harbor during the night. A messenger requests to see you."

The representative nods slightly, his mind turning over the new information. It appears a new possibility has arisen, and he knows he would have to act swiftly and decisively to protect his and the family’s interests.

On the very next day, as Centurione finishes his morning routine with a prayer in the chapel and walks outside, he is suddenly confronted by a dozen of his knights, all clad in armor. Guessing that they have come to petition for a frontal attack, Centurione walks towards them with a smile: “I appreciate your valor…”

“Lord Centurione, we have come to petition…”

“I know, I know, but you must be…”

“For a negotiated surrender.”

“Patient. ……What?”

Centurione is in shock, he couldn’t believe what he just heard. The knights surround him, then opens a small pathway, and the representative suddenly appears and walks straight to Centurione with a faint smile.

“My lord, I know you have fought valiantly, which I admire. Unfortunately, the situation has become untenable. The Greeks… The Romans have completed their sapping, and they can blow up our walls any minutes, and slaughter us all effortlessly. Fortunately, the Romans send their proposal for surrender yesterday, and it is indeed a generous one: If we surrender now, the Romans will spare our lives, we can keep all our weapons, and all belongings which can be moved by foot. The Roman will in addition carry us into the realm of Count Tocco. We therefore strongly urge you to accept such offer of peace.”

“YOU… Traitors!” the veins of Centurione are all exposed by the anger, his face glowing red. He reaches for his sword in subconscious, but finds the left side of his belt empty. He then remembers he left his sword at the gate of the chapel.

“Traitor, what harsh words my lord. But you see, you misunderstands us, we, all of us, only wishes to safeguard your security. None of us wants to see you perish in a hopeless fight.”

Centurione looks around, and to his despair only sees faces cold as stone. He knows all is lost, his men have decided to surrender, and there is nothing he could do.

“Alas, I give my consent.”

“Wise choice my Lord. Tell the Romans that we accept their terms and surrender.”

On 28 May 1417, a sunny morning, the last holding of the County of Achaea, the mighty castle of Glarentza surrender to the Romans.

Nice victory for the Romans at Achaea, the Romans need to keep those cannons and heavily study them. Adapt gunpowder warfare throughout the entire Empire, it will surely make them a harder target against the Ottomans. Keep up the great work 👍👍👍.

They'll definately come in handy in defensive and offensive warfare, both of which the Romans will have plenty of experienceNice victory for the Romans at Achaea, the Romans need to keep those cannons and heavily study them. Adapt gunpowder warfare throughout the entire Empire, it will surely make them a harder target against the Ottomans. Keep up the great work 👍👍👍.

Mehmed dies of a random cannonball to the face, just destroying the Ottoman Empire 🤣🤣🤣They'll definately come in handy in defensive and offensive warfare, both of which the Romans will have plenty of experience

That's the historical fate of Nurhaci Aisingioro lol, Mehmed's fate will be disclosed in another 12 Chapters or so.Mehmed dies of a random cannonball to the face, just destroying the Ottoman Empire 🤣🤣🤣

CHAPTER 10 – A VISITOR IN ITALY

CHAPTER 10 – A VISITOR IN ITALY

- Painting of the pearl of Adriatic, city of Venice, Serene Republic of Venice, circa 1480.

The news of Achaea's swift fall into Roman hands quickly rippled across the Italian peninsula. While many might have anticipated the outcome given the Romans' overwhelming power, they were nonetheless astonished by the speed of their reconquest. The Romans captured Glarentza, a heavily fortified castle, in just about a month, a remarkable feat considering the standards of late-medieval sieges, which could often drag on for months, if not years. People's curiosity was piqued about how the Romans achieved this, and soon, the tale spread through whispers among the surviving Latin defenders.

It transpired that the Romans never intended nor were capable of digging their way through the hard gravel. Instead, they devised a clever ruse. At night, laborers secretly carried dirt and sand from unobserved areas outside Glarentza into the sapping camps under the cover of darkness. During the day, they pretended to dig behind large canvases, only to carry the dirt and sand out of the camps to construct a huge mound. This gave the defenders a false impression of daily progress.

When the mound reached a sufficient height and the morale of the defenders sank to an all-time low, the Romans sent a secret messenger from the seaside to try to persuade a representative of the Giustiniani family. They offered generous terms, appealing to the representative's desire to preserve their trade privileges. The representative, who controlled the port of Glarentza and had numerous connections and influence among the knights and nobles, had no loyalty to Centurione and was eager to maintain their trading privileges. These privileges would be guaranteed and preserved by the Romans if the representative could facilitate a peaceful transfer of Glarentza. Otherwise, they made it clear that no mercy would be shown once the Imperial forces took the castle by force. The trade representative ultimately agreed and fulfilled his part of the bargain.

In June 1417, two crucial meetings discussing the aftermath of Achaea's fall occurred almost simultaneously in Genoa, the nominal benefactor and protector of Achaea, and Venice, the city-state with the most interests and influence in Morea and Achaea. In Genoa, a proposal was brought forward to send a punitive expedition to Morea – the insult against the Serene Republic of Genoa must be repaid with Greek gold or with Greek blood. However, the majority of those present expressed caution, pointing out that Genoa was already embroiled in a long and bloody war against the Duchy of Milan. They had few ships and even fewer men to spare. Given that Achaea had always only nominally been under Genoese control and that Constantinople had agreed to uphold and protect existing Genoese trade interests in the area, most saw military intervention as a waste of valuable resources. An open conflict with the Romans would also pose a great threat to Genovese colony of Galata which were situated next to Constantinople and provided Genoa with vital fund and trade. In the end, Genoa swallowed its pride and signed a formal agreement with Constantinople, acknowledging the change of sovereignty over Achaea.

The Venetians, on the other hand, were far less accommodating. Venice and Rome had extensive diplomatic ties and relations in the past, sometimes cooperative, other times not. In general, Roman-Venetian relations had been relatively cordial over the past five years. The Venetians had successfully dominated the Aegean trade network and sought to protect their holdings rather than expand further. As a result, they saw the severely weakened Constantinople as a potential buffer against the dominant power of the Ottoman Turks, who were still technically at war with Venice following the naval battle of Gallipoli in 1416, although there had been no armed conflicts since the Ottoman navy's crushing defeat. Additionally, the Venetians had gained every possible trade concession from the Romans within Constantinople, to the point where it could be argued that the Romans had fallen under Venetian economic dominance.

When Roman ambassador Nicholas Eudaimonoioannes visited Venice in February 1416, he was warmly welcomed. During his brief stay, Nicholas offered to mediate between the Venetian Republic and the King of Hungary, Sigismund, for the conclusion of peace. He also requested aid in rebuilding the Hexamilion wall that protected the entrance to Morea and urged the formation of a Christian league against the Ottoman Empire. The Venetian Senate gladly accepted the Byzantine proposal to mediate with Sigismund but was hesitant to commit to either of the latter's proposals.

In the year 1417, the Romans' triumphant campaign in Achaea shifted the Venetians' attitude. As the undisputed naval powerhouse in the Aegean Sea, with interests extending deep into Morea and Achaea, the Venetians had long cast covetous eyes on Patras and Glarentza, the two vital trade hubs of Achaea. They had been closely monitoring the Roman campaign, eagerly awaiting an opportunity to seize Patras. However, the swift capture of both Glarentza and Patras by the Romans caught the Venetians off guard, their naval and land forces still unprepared, rendering direct intervention a near impossibility in the short term.

Venice found itself in a predicament. The fall of Glarentza and Patras into Roman hands, along with the potential Roman domination of the Peloponnesus, threatened Venetian interests in the region, a prospect that was unacceptable. Consequently, the Venetian Senate adopted a hardline stance against the Romans, and an official letter was promptly dispatched to Constantinople. Leveraging a lease agreement between Venice and the former Prince of Achaea, Centurione, the Venetians formally demanded that the Romans cede control of Patras to Venice and restore Centurione to Glarentza and several other castles and holdings. This was aimed at restoring a balance of power and checking Roman expansion.

The Romans took the Venetian demand seriously. Accepting the Venetians' terms would be humiliating and would undermine their hard-earned gains. However, the Empire was not in a position to risk a potential open conflict with Venice. A delicate diplomatic balance needed to be struck. On the 6th of July, a Roman delegation of a dozen men, led by Andronikos, Despot of Thessaloniki, and Plethon, a renowned Roman philosopher in Italy, arrived in Venice to negotiate terms. The Venetians greeted them with a polite but cold reception, a stark contrast to the warmth shown to the previous Roman diplomatic mission.

Before the official meeting, Andronikos took a brief tour of the city, fascinated by Venice's industrial might, particularly the immense Arsenal complex, where galleys and firearms were produced in vast quantities monthly. After several days of waiting, the Roman delegation was finally granted a meeting with Doge Tommaso Mocenigo, a war veteran of the failed Nikopolis Crusade in 1396. Initially, the Doge adopted a strong and arrogant stance, refusing to entertain any modifications to their demands and insisting that the Romans accept all terms unconditionally.

The Roman delegation, however, displayed humility yet firmness, remaining patient and refusing to yield under Venetian pressure. The initial meetings ended with no progress for either side. As time wore on, the Venetians' impatience grew, their tone becoming increasingly harsh, culminating in veiled threats of war.

However, the Venetians' true intentions began to emerge. Aware that their truce with Sigismund, emperor of the Holy Roman Empire, was set to expire in April of the following year, and noting the significant rise in the prices of wheat, leather, iron, and other war materials in Venice, Andronikos and Plethon deduced that the Venetians were amassing provisions for a potential war against Sigismund. In such a scenario, Venice could not afford a prolonged conflict in the Aegean, given the threat posed by Sigismund's might in Dalmatia. Sigismund, with the potential to mobilize tens of thousands of men from Hungary, Croatia, and the German states, posed an existential threat to Venice, far greater than the annoyance posed by the Romans.

As autumn approached and the Venetians' bluster failed to achieve its desired effect, their position began to soften. After several rounds of negotiations, on August 14th, 1417, an agreement was finally reached. The Romans would retain Glarentza and "redeem" Patras from Venetian lease, paying an upfront fee of 2,000 ducats and an annual fee of 300 ducats for ten years. Additionally, the Venetian navy and trade fleet would be granted free access to the port of Patras for fifteen years, and Venetian merchants in Patras would enjoy tax exemption for the same duration.

The signing of this agreement marked the conclusion of a successful Roman campaign. However, Andronikos and Plethon did not return home. Instead, they traveled north across the Alps towards the German Archbishopric of Konstanz, where they were invited by Emperor Sigismund to participate in the final stage of the Council of Konstanz. Their mission was to help elect a new pope and resolve the Western Schism, while also discussing the prospect of a Crusade.

[1] The Venetians intervened OTL and gave such terms to Constantinople, which the Romans reluctantly agreed – prolonging the rule of Centurione in a few Latin holdings in Achaea for another decade.

[2] From 1412 to 1423, Emperor Sigismund campaigned intermittently against the Republic of Venice in Italy with the aims of taking the rich Dalmatian cities and cut down Venetian influence in the area. The Venetians on the other hand planned several assassinations attempts on the emperor.

- Painting of the pearl of Adriatic, city of Venice, Serene Republic of Venice, circa 1480.

The news of Achaea's swift fall into Roman hands quickly rippled across the Italian peninsula. While many might have anticipated the outcome given the Romans' overwhelming power, they were nonetheless astonished by the speed of their reconquest. The Romans captured Glarentza, a heavily fortified castle, in just about a month, a remarkable feat considering the standards of late-medieval sieges, which could often drag on for months, if not years. People's curiosity was piqued about how the Romans achieved this, and soon, the tale spread through whispers among the surviving Latin defenders.

It transpired that the Romans never intended nor were capable of digging their way through the hard gravel. Instead, they devised a clever ruse. At night, laborers secretly carried dirt and sand from unobserved areas outside Glarentza into the sapping camps under the cover of darkness. During the day, they pretended to dig behind large canvases, only to carry the dirt and sand out of the camps to construct a huge mound. This gave the defenders a false impression of daily progress.

When the mound reached a sufficient height and the morale of the defenders sank to an all-time low, the Romans sent a secret messenger from the seaside to try to persuade a representative of the Giustiniani family. They offered generous terms, appealing to the representative's desire to preserve their trade privileges. The representative, who controlled the port of Glarentza and had numerous connections and influence among the knights and nobles, had no loyalty to Centurione and was eager to maintain their trading privileges. These privileges would be guaranteed and preserved by the Romans if the representative could facilitate a peaceful transfer of Glarentza. Otherwise, they made it clear that no mercy would be shown once the Imperial forces took the castle by force. The trade representative ultimately agreed and fulfilled his part of the bargain.

In June 1417, two crucial meetings discussing the aftermath of Achaea's fall occurred almost simultaneously in Genoa, the nominal benefactor and protector of Achaea, and Venice, the city-state with the most interests and influence in Morea and Achaea. In Genoa, a proposal was brought forward to send a punitive expedition to Morea – the insult against the Serene Republic of Genoa must be repaid with Greek gold or with Greek blood. However, the majority of those present expressed caution, pointing out that Genoa was already embroiled in a long and bloody war against the Duchy of Milan. They had few ships and even fewer men to spare. Given that Achaea had always only nominally been under Genoese control and that Constantinople had agreed to uphold and protect existing Genoese trade interests in the area, most saw military intervention as a waste of valuable resources. An open conflict with the Romans would also pose a great threat to Genovese colony of Galata which were situated next to Constantinople and provided Genoa with vital fund and trade. In the end, Genoa swallowed its pride and signed a formal agreement with Constantinople, acknowledging the change of sovereignty over Achaea.

The Venetians, on the other hand, were far less accommodating. Venice and Rome had extensive diplomatic ties and relations in the past, sometimes cooperative, other times not. In general, Roman-Venetian relations had been relatively cordial over the past five years. The Venetians had successfully dominated the Aegean trade network and sought to protect their holdings rather than expand further. As a result, they saw the severely weakened Constantinople as a potential buffer against the dominant power of the Ottoman Turks, who were still technically at war with Venice following the naval battle of Gallipoli in 1416, although there had been no armed conflicts since the Ottoman navy's crushing defeat. Additionally, the Venetians had gained every possible trade concession from the Romans within Constantinople, to the point where it could be argued that the Romans had fallen under Venetian economic dominance.

When Roman ambassador Nicholas Eudaimonoioannes visited Venice in February 1416, he was warmly welcomed. During his brief stay, Nicholas offered to mediate between the Venetian Republic and the King of Hungary, Sigismund, for the conclusion of peace. He also requested aid in rebuilding the Hexamilion wall that protected the entrance to Morea and urged the formation of a Christian league against the Ottoman Empire. The Venetian Senate gladly accepted the Byzantine proposal to mediate with Sigismund but was hesitant to commit to either of the latter's proposals.

In the year 1417, the Romans' triumphant campaign in Achaea shifted the Venetians' attitude. As the undisputed naval powerhouse in the Aegean Sea, with interests extending deep into Morea and Achaea, the Venetians had long cast covetous eyes on Patras and Glarentza, the two vital trade hubs of Achaea. They had been closely monitoring the Roman campaign, eagerly awaiting an opportunity to seize Patras. However, the swift capture of both Glarentza and Patras by the Romans caught the Venetians off guard, their naval and land forces still unprepared, rendering direct intervention a near impossibility in the short term.

Venice found itself in a predicament. The fall of Glarentza and Patras into Roman hands, along with the potential Roman domination of the Peloponnesus, threatened Venetian interests in the region, a prospect that was unacceptable. Consequently, the Venetian Senate adopted a hardline stance against the Romans, and an official letter was promptly dispatched to Constantinople. Leveraging a lease agreement between Venice and the former Prince of Achaea, Centurione, the Venetians formally demanded that the Romans cede control of Patras to Venice and restore Centurione to Glarentza and several other castles and holdings. This was aimed at restoring a balance of power and checking Roman expansion.

The Romans took the Venetian demand seriously. Accepting the Venetians' terms would be humiliating and would undermine their hard-earned gains. However, the Empire was not in a position to risk a potential open conflict with Venice. A delicate diplomatic balance needed to be struck. On the 6th of July, a Roman delegation of a dozen men, led by Andronikos, Despot of Thessaloniki, and Plethon, a renowned Roman philosopher in Italy, arrived in Venice to negotiate terms. The Venetians greeted them with a polite but cold reception, a stark contrast to the warmth shown to the previous Roman diplomatic mission.

Before the official meeting, Andronikos took a brief tour of the city, fascinated by Venice's industrial might, particularly the immense Arsenal complex, where galleys and firearms were produced in vast quantities monthly. After several days of waiting, the Roman delegation was finally granted a meeting with Doge Tommaso Mocenigo, a war veteran of the failed Nikopolis Crusade in 1396. Initially, the Doge adopted a strong and arrogant stance, refusing to entertain any modifications to their demands and insisting that the Romans accept all terms unconditionally.

The Roman delegation, however, displayed humility yet firmness, remaining patient and refusing to yield under Venetian pressure. The initial meetings ended with no progress for either side. As time wore on, the Venetians' impatience grew, their tone becoming increasingly harsh, culminating in veiled threats of war.

However, the Venetians' true intentions began to emerge. Aware that their truce with Sigismund, emperor of the Holy Roman Empire, was set to expire in April of the following year, and noting the significant rise in the prices of wheat, leather, iron, and other war materials in Venice, Andronikos and Plethon deduced that the Venetians were amassing provisions for a potential war against Sigismund. In such a scenario, Venice could not afford a prolonged conflict in the Aegean, given the threat posed by Sigismund's might in Dalmatia. Sigismund, with the potential to mobilize tens of thousands of men from Hungary, Croatia, and the German states, posed an existential threat to Venice, far greater than the annoyance posed by the Romans.

As autumn approached and the Venetians' bluster failed to achieve its desired effect, their position began to soften. After several rounds of negotiations, on August 14th, 1417, an agreement was finally reached. The Romans would retain Glarentza and "redeem" Patras from Venetian lease, paying an upfront fee of 2,000 ducats and an annual fee of 300 ducats for ten years. Additionally, the Venetian navy and trade fleet would be granted free access to the port of Patras for fifteen years, and Venetian merchants in Patras would enjoy tax exemption for the same duration.

The signing of this agreement marked the conclusion of a successful Roman campaign. However, Andronikos and Plethon did not return home. Instead, they traveled north across the Alps towards the German Archbishopric of Konstanz, where they were invited by Emperor Sigismund to participate in the final stage of the Council of Konstanz. Their mission was to help elect a new pope and resolve the Western Schism, while also discussing the prospect of a Crusade.

[1] The Venetians intervened OTL and gave such terms to Constantinople, which the Romans reluctantly agreed – prolonging the rule of Centurione in a few Latin holdings in Achaea for another decade.

[2] From 1412 to 1423, Emperor Sigismund campaigned intermittently against the Republic of Venice in Italy with the aims of taking the rich Dalmatian cities and cut down Venetian influence in the area. The Venetians on the other hand planned several assassinations attempts on the emperor.

Great chapter, hopefully good things come out of the meeting between Emperor Sigismund and Prince Andronikos. A potential Crusade against the Ottomans with a resurging Roman Empire would be great to read about. I hope the Venetians don't try anything to problematic to hamper the Romans in their goal of restoring their power. Keep up the good work 👍👍👍👍

CHAPTER 10 – A VISITOR IN ITALY

View attachment 898183

- Painting of the pearl of Adriatic, city of Venice, Serene Republic of Venice, circa 1480.

The news of Achaea's swift fall into Roman hands quickly rippled across the Italian peninsula. While many might have anticipated the outcome given the Romans' overwhelming power, they were nonetheless astonished by the speed of their reconquest. The Romans captured Glarentza, a heavily fortified castle, in just about a month, a remarkable feat considering the standards of late-medieval sieges, which could often drag on for months, if not years. People's curiosity was piqued about how the Romans achieved this, and soon, the tale spread through whispers among the surviving Latin defenders.

It transpired that the Romans never intended nor were capable of digging their way through the hard gravel. Instead, they devised a clever ruse. At night, laborers secretly carried dirt and sand from unobserved areas outside Glarentza into the sapping camps under the cover of darkness. During the day, they pretended to dig behind large canvases, only to carry the dirt and sand out of the camps to construct a huge mound. This gave the defenders a false impression of daily progress.