Scotland would have 800.000 + population in 1600, I think its possible, but Scotland has to be careful and it will be a long process for it to happen.I don’t think that’s feasible. They don’t have nearly the same population or wealth

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Anno Obumbratio: A 16th Century Alternate History

- Thread starter DrakeRlugia

- Start date

Threadmarks

View all 53 threadmarks

Reader mode

Reader mode

Recent threadmarks

Chapter 40. Memoriae Sacrum Addenum: Additional AI Portraits / Images Chapter 41. Rogues of Italy Chapter 42. The Imperial Division Chapter 43. The Council of Lucerne Chapter 44. The Fürstenkrieg — The Italian War of 1555-1562; Part 1. Chapter 45. An English Rose (With Thorns) Addendum: Dynastic Trees (Updated to 1559)Well, Charles would be looking for a new viceroy / governor in Spain to begin with.Nice, but how would this affect Castile/Aragon?

The Netherlands only had about 1.5m c. ~1600, so Scotland isn't too far off, but I think the main thing that would hinder Scotland is that it was a very poor country: difficult terrain, poor roads, limited transport, and little trade between different areas of the country. Scotland's ports did handle a good deal of trade throughout the sixteenth century, though some sectors of the economy declined (the cloth trade for instance). Scotland had a pretty lively trade with the Baltics, particularly Danzig, Königsburg, and Riga, but this was mostly related to the trade of grain, as those regions provided needed grain during bad harvests. Still, there were colonies of Scottish traders in those cities. The other main issue is that Scotland's economy is far from the proto-capitalism of the Low Countries, where trade is the most important commodity, alongside the fisheries and shipbuilding.Scotland would have 800.000 + population in 1600, I think its possible, but Scotland has to be careful and it will be a long process for it to happen.

That, and Scotland's kings have a bad habit of going off and getting killed, leaving behind infant monarchs and regencies, continually throwing the kingdom into crisis, especially when rival factions came into conflict, which was often. If the present young monarch, Alexander IV, can live longer than a few decades, he might be able to give Scotland some needed space to breathe. But that would also probably mean detangling it's foreign policy from France and staking out a more pro-English foreign policy...

Chapter 13. Flames of Reform

Chapter 13. Flames of Reform

1520-1521 – Germany

“Although indulgences are the very merits of Christ and of His saints and so should be treated with all reverence, they have in fact nonetheless become a shocking exercise of greed.”

— Martin Luther, Ninety-Five Theses.

Music Accompaniment: Spirit Come, Bourgeois

Diet of Worms, 1521.

Following Charles’ departure from Spain, the imperial party landed safely at Ostend on May 26th, 1520—including Charles, his wife—Mary, several important members of Charles suite such as the Lord of Chièvres and Chancellor Gattinara, and members of Mary’s suite, as well—such as Charles Brandon and the head of the queen’s household, Anne of Croÿ. Germaine of Foix, the widow of Ferdinand of Aragon and the king’s step-grandmother had also followed the king abroad—whose marriage he had arranged to Johann of Brandenburg-Ansbach, to secure the support of the Elector of Brandenburg for his election. From Ostend, Charles and his retinue proceeded to Mechlen, where they were greeted by Charles’ aunt and governor of the Low Countries, Margaret of Austria. “The Archduchess Margaret was plainly pleased to see the king,” Anne of Croÿ wrote in her diary. “They embraced, and she bade her nephew sit and tell her of his travails in Spain. It was a most happy reunion—and the archduchess was pleased to finally lay eyes upon her nephew’s bride, as well. Even once the king and his suite retired, the queen remained with the archduchess for a long time after… discussing the troubles that she and the king had endured in Spain. The queen and the archduchess got on splendidly—from that day forward, the queen had acquired an important ally within her new famille.” Charles took the chance of his time at Mechlen to hold an interview with England’s longtime ambassador in the Low Countries, Thomas Boleyn—where Charles provided the ambassador with several letters—one to be passed on to his aunt, the queen-regent: and another to be given forward to Thomas Wolsey, the Bishop of Lincoln. Charles’ letter to his aunt outlined the mutual interests that lie between both kingdoms, and that with the ceaseless ambitions of the French King, they ought to band together in mutual alliance. The king’s letter to Wolsey was more coded—in it, Charles made plain that he knew of the Bishop’s great friendship with France. He played on the Bishop’s vanity, writing: “My very good friend—your abilities are too great to be wasted simply as a minister amongst many; there are greater roles that you could play within our Holy Church—as I am sure you are all too aware of. Accept my friendship, and spurn that of France—and I shall help you however I can.” The king also promised Wolsey a pension of 7000 ducats.

Charles and Mary remained in the Low Countries only a brief period; they soon resumed their journey to Aix-la-Chapelle, or Aachen—the traditional place where the prince chosen by the Electors of the Holy Roman Empire would be crowned as King of Germany—the first step to being recognized as emperor. This was typically followed by the Italienzug where the elected emperor was provided with troops by the Reichstag to travel to Rome to be crowned by the Pope. This had been dispensed with in the previous reign, as Maximilian had been prevented from journeying to Rome by the Venetians—he was instead proclaimed emperor in 1508, taking the title of elected emperor which was recognized by the Pope. There were high hopes amongst many that Charles might revive the practice of the Italienzug and be properly crowned. Charles and his retinue arrived in Aix-la-Chapelle in October of 1520—with the king and queen staying in the Stadtpalais of the Mayor of Aix-la-Chapelle, Everhard von Haren.

On the day of the coronation, Charles and Mary arrived at the Palatine Chapel of Aachen—part of the Cathedral of Aachen, the Palatine Chapel was one of the few remaining parts of the Palace of Aachen, which had been built by Charlemagne. The king was met at the entrance of the church by the three spiritual electors, the Archbishops of Cologne, Mainz, and Trier. The Archbishop of Cologne, as the local metropolitan and chief officiant provided a short prayer before the king and queen proceeded into the church, followed by the archbishops. The chapel was sumptuously arrayed, perhaps more than in any other era—and both the king and queen’s wardrobes matched that; with the queen arrayed in Spanish styled gown of pink floral silk—with the king was dressed in an overgown of purple cloth of gold, etched with golden brocade. His shirt was linen, with a doublet of cream—which were paired with Spanish style black velvet hose and stockings. The coronation was well attended by the German nobility—more numerous than splendid in any other time. Following mass, the Archbishop of Cologne put six questions to the emperor elect: “Will you defend the Holy Faith? Will you defend the Holy Church? Will you defend the kingdom? Will you maintain the laws of the empire? Will you maintain justice? Will you show due submission to His Holiness, the Pope?” Each question was met with the emperor elect stating in response: “I will.” Charles was then allowed to lay two fingers his on the high altar—swearing his oath and asking those assembled to accept him as their king.

Charlemagne by Albrecht Dürer, c. 1512

This proceeded to the anointment—the oil used was a chrism of catechumens, typically used during baptism and widely believed to strengthen those baptized to turn away from evil, temptation, and sin. Charles was anointed upon his head, shoulders, and breast by the Archbishop of Cologne, with the archbishop stating: “Let these hands be anointed, as kings and prophets were anointed; and as Samuel anointed David to be king may you be blessed and established king in this kingdom over this people, whom the Lord, your God has given you you to rule and govern. He vouchsafes to grant, who with the Father and Holy Spirit, lives, and reigns…” Charles was then invested in the imperial robes, along with the imperial sword, scepter, and orb. It was only after this that the Archbishop of Cologne set the imperial crown upon his head, co-jointly with the other archbishops. At this point, Charles once more recited his coronation oath—in both Latin and German and was enthroned. Afterwards, a homily was given by the Archbishop of Mainz. Following Charles’ crowning came that of Mary's. This was a pivotal event, for Mary would be the first to be crowned Queen of Germany in over a century—the last crowning had occurred in 1414, when Barbara of Cilli had been crowned. Mary’s coronation was conducted co-jointly by the Archbishop of Mainz and the Archbishop of Trier. Following the singing of a Te Deum, the queen was anointed with the following of prayers, before being crowned herself—a much briefer ceremony compared to that of her husbands. After this, the emperor, now crowned, proceeded to dub several men as knights using the imperial sword. After a final mass was concluded, the emperor was named a canon of the Palatine Chapel.

Though Charles was now crowned and could assume the title of elected emperor as his grandfather had, his position was far from secure. In Spain, the Comunidad revolt was in full force—and would not be contained until almost two more years, ultimately requiring several concessions from the emperor. In Germany, it was not the specter of revolt, but that of reform that troubled the empire. Martin Luther, a monk from Saxony, had shocked the known world in 1517 when he had nailed his ninety-five theses to the door of the Wittenburg church—a document which attacked the abuses and corruption of the Roman Church. The theses spread widely—first in Latin, before being translated into German in 1518; Luther’s work spread rapidly, and by 1519 was available in France, England, and Italy. Luther’s theses had also been sent to the Archbishop of Mainz, Albert of Brandenburg—who promptly sent them to Rome to be examined for heresy. Pope Leo X moved slowly, employing a series of Papal theologians and envoys against the monk, which only turned Martin Luther further against the papacy. When a heresy case was opened against Luther, he was examined at Augsburg in 1518, where he defended himself against the Papal Legate, Cardinal Caejan—the main point of the examination being the Pope’s right to sell indulges; the examination soon disintegrated into a shouting match: “His Holiness abuses scripture!” Luther retorted. “I deny that he is above scripture.” His meeting with papal nuncio Karl von Miltitz was more constructive, with Luther agreeing to remain silent if his enemies should do so; but this was not to be. Johann Eck, a theologian, was determined to poke holes into Luther’s doctrine and do so publicly. He hosted a disputation in Leipzig in 1519 with one of Luther’s close allies, with Luther invited to speak as well. “Luther was bold in his assertions,” One spectator wrote. “He debated that Matthew 16:18 does not confer unto the Pope’s any exclusive right to interpret scripture. He went further—stating that this meant that neither the Pope nor any church council could be considered infallible…” Eck—scandalized by the monk’s bold assertions, was determined to bring about his defeat. “He is nothing more than the Jan Hus of our century,” One ally of Eck wrote. “He must be stamped out.”

Luther’s situation moved quickly to a climax in the summer of 1520, shortly before the emperor’s coronation. Pope Leo X issued a papal bull, Exsurge Domine, warning Luther that he risked excommunication unless he recanted forty-one sentences from his writings, including his theses. He was given sixty days to do so. In the autumn, Johann Eck proclaimed the bull in Meissen and other towns within Saxony. Though Karl von Milititz attempted to broker a solution, but Luther was unrepentant and defiant: “Whoever wrote this bull—he is the Antichrist. I protest before God, our Lord Jesus, his sacred angels, and whole world that with my whole heart I dissent from the damnation of this bull; that I curse and execrate it as sacrilege and blasphemy of Christ, God’s Son and our Lord. This be my recantation: O bull, thou daughter of bulls.” In December, Luther and Philip Melanchthon invited the local university faculty and students to assemble at the Elster Gate in Wittenburg—there, a bonfire was lit and Luther cosigned volumes of canon law, papal constitutions, and other theological works into the flames: including a copy of the papal bull. Luther’s explanation was simple: “Since they have burned my books; I burn theirs. Canon law was included because it makes the Pope a god on earth; so far I have merely fooled with this business of the Pope. All my articles condemned by the Antichrist are Christian. Seldom has the Pope overcome anyone with Scripture and with reason.” In response, Luther was formally excommunicated in January of 1521.

Martin Luther as an Augustinian Monk

In response to the growing crisis, one of the first acts of Charles as emperor was to convene a diet to check the growth of the dangerous opinions espoused by Martin Luther. The Diet was assembled at the imperial city of Worms, and Martin Luther was summoned by the emperor to offer an answer—either to recant his views or reaffirm them. Though Luther agreed to attend, many of his supporters viewed the summons with trepidation, seeing it as nothing more than a death sentence. The Elector of Saxony sought to obtain reassurances from Charles V that if Luther showed before the diet, he would be promised safe conduct to and from the meeting, which the emperor readily agreed too. When Johann von Eck suggested that the emperor should use the diet to seize Luther, the emperor is said to have retorted: “I will not blush like my predecessor Sigismund.” Though the emperor was aware of the rot within his Holy Church and knew the need of some type of reform, he was no friend or ally to Luther; his refusal to aid Luther’s enemies was because of his own position: he was the elected emperor—the universal monarch; he was not the Pope’s lackey or lapdog, to do his bidding as he pleased. Charles was also forced to look at his own position—Luther’s ideas were rapidly growing in popularity with each passing day, and he had acquired a powerful benefactor in the person of the Elector of Saxony. If the emperor were to arrest the monk and condemn him to the flames—he would only make him a martyr. Martyrdom might also spur conflict in Germany… and the emperor was aware of his lack of funds owing to the present crisis in Spain, and he had no troops on which he could rely in the heart of Germany.

The Diet of Worms as it would later be called formally opened on January 28th 1521—and though Luther was a primary concern, the diet had also been convened to settle the questions of the governance of the emperor’s vast dominions—the Habsburg inheritance of Austria; the Burgundian inheritance of the Low Countries; the Spanish inheritance which included the kingdoms of Castile and Aragon in Spain—and the kingdoms of Naples and Sicily in Italy. In the spring of 1521, the emperor decided that he would name his wife, the Empress Mary, as regent of the Low Countries, alongside his aunt, Margaret, as governor. The patent for the empress’s position stated: “It is my wish that the pair of you—being amicable friends and most understanding of my wishes, will do all that is required to maintain the prosperity of these lands.” Regarding Spain, Charles reversed course from the Edict of Worms that in 1520 had named his brother a traitor. With Ferdinand liberated by royalist troops, Charles wrote to his lieutenants in Spain: “The Infante shall be given a full and total pardon; he has committed no crimes against us or our person.” Charles had never doubted his brother; his being named as a traitor had been merely to spook the rebel forces. “When the rebel communities have been dealt with and peace restored—I intend to name Ferdinand as my representative in Spain as regent and Viceroy of Castile and Aragon when I am abroad.”

In terms of the empire, the emperor was also dedicated to a continuance of the project of the reform of the imperial government that had been carried out in the time of Emperor Maximilian. The German princes were adamant that the emperor revive the Reichsregiment—an organ of government that had been devised in the time of Maximilian, comprised of twenty temporal and spiritual princes to deal with matters of finances, foreign affairs, and war. The organ had floundered due to Maximilian’s refusal to cooperate with it. Its re-establishment was demanded as part of the Wahlkapitulation that the electors had presented to Charles V in 1519. Charles V endorsed the recreation of the Reichsregiment, but stipulated that it was a consultive body, and should only have decision-making powers whenever he was absent from the empire. The diet also agreed on the establishment of an updated Imperial Register—a list of imperial estates which specified the precise amount of money and number of troops that each state had to supply to the Imperial Army, to provide provisions for the eventual army that would accompany Charles on his Italienzug. It was decided the imperial force should consist of some 20,000 infantry and 4,000 cavalry. On taxation, there were pressing discussions regarding the need to fund the imperial government, and the less efficient forms that had been tried previously—primarily the Gemeiner Pfennig that had been introduced by Maximilian in 1495 and withdrawn less than a decade later. In deliberations with the diet, Charles V also made an important decision regarding several governmental organs founded by his grandfather that had combined the duties of the imperial crown with those of the Habsburgs hereditary dominions in Austria. These were primarily the Reichshofrat, or Aulic Council; the Gehimer Rat, or Privy Council; and the Reichhofkanzlei, or Imperial Chancery. Charles V decreed that these institutions would be transferred from Innsbruck to Brussels—the center of the emperor’s dominions in the Low Countries. While the Archbishop of Mainz was the nominal head of the Imperial Chancery as Archchancellor of Germany, in practice the chancery was governed by a vice-chancellor—with the emperor naming Gattinara, his Burgundian Chancellor to the position. It was also decided that the Imperial Chancery would absorb the Burgundian Chancery. Though the various other imperial organizations received no authority within the Low Countries, which maintained their own institutions, the emperor’s decree still represented an important move—putting all the organizations that represented the emperor’s dominions within the empire in one single place. Perhaps the emperor had some hope that his wife and aunt might be able to provide appropriate oversight to these organizations that had previously been left to their own devices in Tyrol.

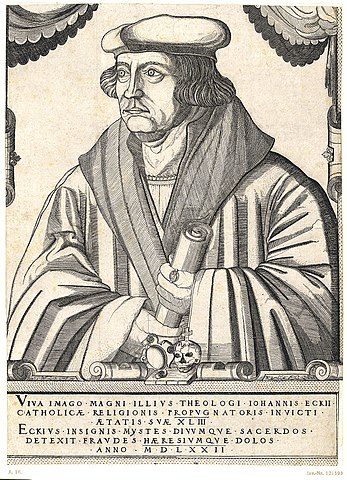

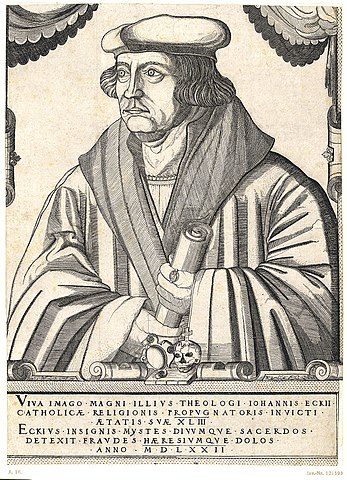

Johann von Eck, one of Martin Luther's fiercest critics.

Martin Luther arrived in Worms on April 16th, 1521; at this point, the diet had been in progress for nearly four months. Luther was accompanied by Jeromee Schurff, a professor of canon law, was to service as Luther’s lawyer before the diet. Luther was commanded to appear before the diet the next day. The imperial marshal, Urach von Pappenheim as well as the imperial herald, Caspar Sturm, arrived at Luther’s dwellings on the next day, April 17th, to bring him before the diet—with Luther reminded that he should only answer questions from the presiding officer of the diet, Luther’s avowed enemy: Johann von Eck. “Is this collection of books yours?” Eck was reported to have said. “Are you prepared to revoke the heresies within them?” At this, Professor Schruff was adroit, asking that the titles be read out. Some twenty-five total works were listed, from the Ninety-five Theses to more recent publications Luther had produced, such as Address to the Christian Nobility and On the Papacy in Rome. Luther asked if he might have more time to formulate a proper answer—and it was agreed; he was to return the next day at the same time.

On April 18th, the diet was once more assembled, and Luther was once again asked regarding his work. “I apologize, my lords, that I lack the etiquette of the court. These writings are all mine—but they are not all of one sort.” Luther went on to place his writings into three categories: The first works that were well received, even by his most fervent enemies. Those he would not reject. The second included writings that attacked the abuses, lies, and desolation of the Christian world and the Papacy in particular. “I cannot reject these—for to do so would allow these abuses to continue. Were I to retract them, then the door is only open to further oppression. If I recant these—then I am only strengthening tyranny.” The third category of writings primarily attacked individuals. “I apologize for the harsh tones contained within, but I do not reject the substance of what is within.” Luther concluded his defense simply: “If there is scripture that shows my writings in error—then show me. I would gladly reject them. Unless I am convinced by the testimony of the scriptures or by clear reason, for I do not trust in the Pope or church councils alone; is it well known that they have erred and often contradicted themselves. I am bound by scriptures I have quoted and my conscience is captive by the word of God. I cannot and will not recant anything since it is neither safe nor right to go against conscience. Here I stand—for I cannot do otherwise. May God help me. Amen.”

Johann von Eck was quick to move onto the attack: “Martin—there is no one of the heresies which have torn he bosom of the church, which has not derived its origin from the various interpretations of the Scripture. The Bible itself is the arsenal whence each innovator has drawn his deceptive arguments. It was with biblical texts that Pelagius and Arius maintained their doctrines; Arius, for instance, found the negation of the eternity of the Word—an eternity which you admit, in this verse of the New Testament—Joseph knew not his wife till she had brought forth her first-born son; and he said, in the same way that you say, that this passage enchained him. When the fathers of the Council of Constance condemned this proposition of John Hus—The church of Jesus Christ is only the community of the elect, they condemned an error; for the church, like a good mother, embraces within her arms all who bear the name of Christian, all who are called to enjoy the Celestial beatitude.”

The diet was soon forced to break into private conferences, while discussions were held to determine Luther’s fate—but he was not arrested at Worms, and was able to leave, owing to the letter of safe conduct that the Elector of Saxony had obtained from him. Fearing for Luther’s safety, the elector took the extraordinary step of sending men to fake a highway attack upon Luther—with orders that he should be abducted and brought to safety at Wartberg castle, where he would soon be hidden away. In May, Charles V promulgated the Edict of Worms with support from the diet. Luther was condemned as a notorious heretic, and citizens were forbidden from propagating his ideas.

1520-1521 – Germany

“Although indulgences are the very merits of Christ and of His saints and so should be treated with all reverence, they have in fact nonetheless become a shocking exercise of greed.”

— Martin Luther, Ninety-Five Theses.

Music Accompaniment: Spirit Come, Bourgeois

Diet of Worms, 1521.

Following Charles’ departure from Spain, the imperial party landed safely at Ostend on May 26th, 1520—including Charles, his wife—Mary, several important members of Charles suite such as the Lord of Chièvres and Chancellor Gattinara, and members of Mary’s suite, as well—such as Charles Brandon and the head of the queen’s household, Anne of Croÿ. Germaine of Foix, the widow of Ferdinand of Aragon and the king’s step-grandmother had also followed the king abroad—whose marriage he had arranged to Johann of Brandenburg-Ansbach, to secure the support of the Elector of Brandenburg for his election. From Ostend, Charles and his retinue proceeded to Mechlen, where they were greeted by Charles’ aunt and governor of the Low Countries, Margaret of Austria. “The Archduchess Margaret was plainly pleased to see the king,” Anne of Croÿ wrote in her diary. “They embraced, and she bade her nephew sit and tell her of his travails in Spain. It was a most happy reunion—and the archduchess was pleased to finally lay eyes upon her nephew’s bride, as well. Even once the king and his suite retired, the queen remained with the archduchess for a long time after… discussing the troubles that she and the king had endured in Spain. The queen and the archduchess got on splendidly—from that day forward, the queen had acquired an important ally within her new famille.” Charles took the chance of his time at Mechlen to hold an interview with England’s longtime ambassador in the Low Countries, Thomas Boleyn—where Charles provided the ambassador with several letters—one to be passed on to his aunt, the queen-regent: and another to be given forward to Thomas Wolsey, the Bishop of Lincoln. Charles’ letter to his aunt outlined the mutual interests that lie between both kingdoms, and that with the ceaseless ambitions of the French King, they ought to band together in mutual alliance. The king’s letter to Wolsey was more coded—in it, Charles made plain that he knew of the Bishop’s great friendship with France. He played on the Bishop’s vanity, writing: “My very good friend—your abilities are too great to be wasted simply as a minister amongst many; there are greater roles that you could play within our Holy Church—as I am sure you are all too aware of. Accept my friendship, and spurn that of France—and I shall help you however I can.” The king also promised Wolsey a pension of 7000 ducats.

Charles and Mary remained in the Low Countries only a brief period; they soon resumed their journey to Aix-la-Chapelle, or Aachen—the traditional place where the prince chosen by the Electors of the Holy Roman Empire would be crowned as King of Germany—the first step to being recognized as emperor. This was typically followed by the Italienzug where the elected emperor was provided with troops by the Reichstag to travel to Rome to be crowned by the Pope. This had been dispensed with in the previous reign, as Maximilian had been prevented from journeying to Rome by the Venetians—he was instead proclaimed emperor in 1508, taking the title of elected emperor which was recognized by the Pope. There were high hopes amongst many that Charles might revive the practice of the Italienzug and be properly crowned. Charles and his retinue arrived in Aix-la-Chapelle in October of 1520—with the king and queen staying in the Stadtpalais of the Mayor of Aix-la-Chapelle, Everhard von Haren.

On the day of the coronation, Charles and Mary arrived at the Palatine Chapel of Aachen—part of the Cathedral of Aachen, the Palatine Chapel was one of the few remaining parts of the Palace of Aachen, which had been built by Charlemagne. The king was met at the entrance of the church by the three spiritual electors, the Archbishops of Cologne, Mainz, and Trier. The Archbishop of Cologne, as the local metropolitan and chief officiant provided a short prayer before the king and queen proceeded into the church, followed by the archbishops. The chapel was sumptuously arrayed, perhaps more than in any other era—and both the king and queen’s wardrobes matched that; with the queen arrayed in Spanish styled gown of pink floral silk—with the king was dressed in an overgown of purple cloth of gold, etched with golden brocade. His shirt was linen, with a doublet of cream—which were paired with Spanish style black velvet hose and stockings. The coronation was well attended by the German nobility—more numerous than splendid in any other time. Following mass, the Archbishop of Cologne put six questions to the emperor elect: “Will you defend the Holy Faith? Will you defend the Holy Church? Will you defend the kingdom? Will you maintain the laws of the empire? Will you maintain justice? Will you show due submission to His Holiness, the Pope?” Each question was met with the emperor elect stating in response: “I will.” Charles was then allowed to lay two fingers his on the high altar—swearing his oath and asking those assembled to accept him as their king.

Charlemagne by Albrecht Dürer, c. 1512

This proceeded to the anointment—the oil used was a chrism of catechumens, typically used during baptism and widely believed to strengthen those baptized to turn away from evil, temptation, and sin. Charles was anointed upon his head, shoulders, and breast by the Archbishop of Cologne, with the archbishop stating: “Let these hands be anointed, as kings and prophets were anointed; and as Samuel anointed David to be king may you be blessed and established king in this kingdom over this people, whom the Lord, your God has given you you to rule and govern. He vouchsafes to grant, who with the Father and Holy Spirit, lives, and reigns…” Charles was then invested in the imperial robes, along with the imperial sword, scepter, and orb. It was only after this that the Archbishop of Cologne set the imperial crown upon his head, co-jointly with the other archbishops. At this point, Charles once more recited his coronation oath—in both Latin and German and was enthroned. Afterwards, a homily was given by the Archbishop of Mainz. Following Charles’ crowning came that of Mary's. This was a pivotal event, for Mary would be the first to be crowned Queen of Germany in over a century—the last crowning had occurred in 1414, when Barbara of Cilli had been crowned. Mary’s coronation was conducted co-jointly by the Archbishop of Mainz and the Archbishop of Trier. Following the singing of a Te Deum, the queen was anointed with the following of prayers, before being crowned herself—a much briefer ceremony compared to that of her husbands. After this, the emperor, now crowned, proceeded to dub several men as knights using the imperial sword. After a final mass was concluded, the emperor was named a canon of the Palatine Chapel.

Though Charles was now crowned and could assume the title of elected emperor as his grandfather had, his position was far from secure. In Spain, the Comunidad revolt was in full force—and would not be contained until almost two more years, ultimately requiring several concessions from the emperor. In Germany, it was not the specter of revolt, but that of reform that troubled the empire. Martin Luther, a monk from Saxony, had shocked the known world in 1517 when he had nailed his ninety-five theses to the door of the Wittenburg church—a document which attacked the abuses and corruption of the Roman Church. The theses spread widely—first in Latin, before being translated into German in 1518; Luther’s work spread rapidly, and by 1519 was available in France, England, and Italy. Luther’s theses had also been sent to the Archbishop of Mainz, Albert of Brandenburg—who promptly sent them to Rome to be examined for heresy. Pope Leo X moved slowly, employing a series of Papal theologians and envoys against the monk, which only turned Martin Luther further against the papacy. When a heresy case was opened against Luther, he was examined at Augsburg in 1518, where he defended himself against the Papal Legate, Cardinal Caejan—the main point of the examination being the Pope’s right to sell indulges; the examination soon disintegrated into a shouting match: “His Holiness abuses scripture!” Luther retorted. “I deny that he is above scripture.” His meeting with papal nuncio Karl von Miltitz was more constructive, with Luther agreeing to remain silent if his enemies should do so; but this was not to be. Johann Eck, a theologian, was determined to poke holes into Luther’s doctrine and do so publicly. He hosted a disputation in Leipzig in 1519 with one of Luther’s close allies, with Luther invited to speak as well. “Luther was bold in his assertions,” One spectator wrote. “He debated that Matthew 16:18 does not confer unto the Pope’s any exclusive right to interpret scripture. He went further—stating that this meant that neither the Pope nor any church council could be considered infallible…” Eck—scandalized by the monk’s bold assertions, was determined to bring about his defeat. “He is nothing more than the Jan Hus of our century,” One ally of Eck wrote. “He must be stamped out.”

Luther’s situation moved quickly to a climax in the summer of 1520, shortly before the emperor’s coronation. Pope Leo X issued a papal bull, Exsurge Domine, warning Luther that he risked excommunication unless he recanted forty-one sentences from his writings, including his theses. He was given sixty days to do so. In the autumn, Johann Eck proclaimed the bull in Meissen and other towns within Saxony. Though Karl von Milititz attempted to broker a solution, but Luther was unrepentant and defiant: “Whoever wrote this bull—he is the Antichrist. I protest before God, our Lord Jesus, his sacred angels, and whole world that with my whole heart I dissent from the damnation of this bull; that I curse and execrate it as sacrilege and blasphemy of Christ, God’s Son and our Lord. This be my recantation: O bull, thou daughter of bulls.” In December, Luther and Philip Melanchthon invited the local university faculty and students to assemble at the Elster Gate in Wittenburg—there, a bonfire was lit and Luther cosigned volumes of canon law, papal constitutions, and other theological works into the flames: including a copy of the papal bull. Luther’s explanation was simple: “Since they have burned my books; I burn theirs. Canon law was included because it makes the Pope a god on earth; so far I have merely fooled with this business of the Pope. All my articles condemned by the Antichrist are Christian. Seldom has the Pope overcome anyone with Scripture and with reason.” In response, Luther was formally excommunicated in January of 1521.

Martin Luther as an Augustinian Monk

In response to the growing crisis, one of the first acts of Charles as emperor was to convene a diet to check the growth of the dangerous opinions espoused by Martin Luther. The Diet was assembled at the imperial city of Worms, and Martin Luther was summoned by the emperor to offer an answer—either to recant his views or reaffirm them. Though Luther agreed to attend, many of his supporters viewed the summons with trepidation, seeing it as nothing more than a death sentence. The Elector of Saxony sought to obtain reassurances from Charles V that if Luther showed before the diet, he would be promised safe conduct to and from the meeting, which the emperor readily agreed too. When Johann von Eck suggested that the emperor should use the diet to seize Luther, the emperor is said to have retorted: “I will not blush like my predecessor Sigismund.” Though the emperor was aware of the rot within his Holy Church and knew the need of some type of reform, he was no friend or ally to Luther; his refusal to aid Luther’s enemies was because of his own position: he was the elected emperor—the universal monarch; he was not the Pope’s lackey or lapdog, to do his bidding as he pleased. Charles was also forced to look at his own position—Luther’s ideas were rapidly growing in popularity with each passing day, and he had acquired a powerful benefactor in the person of the Elector of Saxony. If the emperor were to arrest the monk and condemn him to the flames—he would only make him a martyr. Martyrdom might also spur conflict in Germany… and the emperor was aware of his lack of funds owing to the present crisis in Spain, and he had no troops on which he could rely in the heart of Germany.

The Diet of Worms as it would later be called formally opened on January 28th 1521—and though Luther was a primary concern, the diet had also been convened to settle the questions of the governance of the emperor’s vast dominions—the Habsburg inheritance of Austria; the Burgundian inheritance of the Low Countries; the Spanish inheritance which included the kingdoms of Castile and Aragon in Spain—and the kingdoms of Naples and Sicily in Italy. In the spring of 1521, the emperor decided that he would name his wife, the Empress Mary, as regent of the Low Countries, alongside his aunt, Margaret, as governor. The patent for the empress’s position stated: “It is my wish that the pair of you—being amicable friends and most understanding of my wishes, will do all that is required to maintain the prosperity of these lands.” Regarding Spain, Charles reversed course from the Edict of Worms that in 1520 had named his brother a traitor. With Ferdinand liberated by royalist troops, Charles wrote to his lieutenants in Spain: “The Infante shall be given a full and total pardon; he has committed no crimes against us or our person.” Charles had never doubted his brother; his being named as a traitor had been merely to spook the rebel forces. “When the rebel communities have been dealt with and peace restored—I intend to name Ferdinand as my representative in Spain as regent and Viceroy of Castile and Aragon when I am abroad.”

In terms of the empire, the emperor was also dedicated to a continuance of the project of the reform of the imperial government that had been carried out in the time of Emperor Maximilian. The German princes were adamant that the emperor revive the Reichsregiment—an organ of government that had been devised in the time of Maximilian, comprised of twenty temporal and spiritual princes to deal with matters of finances, foreign affairs, and war. The organ had floundered due to Maximilian’s refusal to cooperate with it. Its re-establishment was demanded as part of the Wahlkapitulation that the electors had presented to Charles V in 1519. Charles V endorsed the recreation of the Reichsregiment, but stipulated that it was a consultive body, and should only have decision-making powers whenever he was absent from the empire. The diet also agreed on the establishment of an updated Imperial Register—a list of imperial estates which specified the precise amount of money and number of troops that each state had to supply to the Imperial Army, to provide provisions for the eventual army that would accompany Charles on his Italienzug. It was decided the imperial force should consist of some 20,000 infantry and 4,000 cavalry. On taxation, there were pressing discussions regarding the need to fund the imperial government, and the less efficient forms that had been tried previously—primarily the Gemeiner Pfennig that had been introduced by Maximilian in 1495 and withdrawn less than a decade later. In deliberations with the diet, Charles V also made an important decision regarding several governmental organs founded by his grandfather that had combined the duties of the imperial crown with those of the Habsburgs hereditary dominions in Austria. These were primarily the Reichshofrat, or Aulic Council; the Gehimer Rat, or Privy Council; and the Reichhofkanzlei, or Imperial Chancery. Charles V decreed that these institutions would be transferred from Innsbruck to Brussels—the center of the emperor’s dominions in the Low Countries. While the Archbishop of Mainz was the nominal head of the Imperial Chancery as Archchancellor of Germany, in practice the chancery was governed by a vice-chancellor—with the emperor naming Gattinara, his Burgundian Chancellor to the position. It was also decided that the Imperial Chancery would absorb the Burgundian Chancery. Though the various other imperial organizations received no authority within the Low Countries, which maintained their own institutions, the emperor’s decree still represented an important move—putting all the organizations that represented the emperor’s dominions within the empire in one single place. Perhaps the emperor had some hope that his wife and aunt might be able to provide appropriate oversight to these organizations that had previously been left to their own devices in Tyrol.

Johann von Eck, one of Martin Luther's fiercest critics.

Martin Luther arrived in Worms on April 16th, 1521; at this point, the diet had been in progress for nearly four months. Luther was accompanied by Jeromee Schurff, a professor of canon law, was to service as Luther’s lawyer before the diet. Luther was commanded to appear before the diet the next day. The imperial marshal, Urach von Pappenheim as well as the imperial herald, Caspar Sturm, arrived at Luther’s dwellings on the next day, April 17th, to bring him before the diet—with Luther reminded that he should only answer questions from the presiding officer of the diet, Luther’s avowed enemy: Johann von Eck. “Is this collection of books yours?” Eck was reported to have said. “Are you prepared to revoke the heresies within them?” At this, Professor Schruff was adroit, asking that the titles be read out. Some twenty-five total works were listed, from the Ninety-five Theses to more recent publications Luther had produced, such as Address to the Christian Nobility and On the Papacy in Rome. Luther asked if he might have more time to formulate a proper answer—and it was agreed; he was to return the next day at the same time.

On April 18th, the diet was once more assembled, and Luther was once again asked regarding his work. “I apologize, my lords, that I lack the etiquette of the court. These writings are all mine—but they are not all of one sort.” Luther went on to place his writings into three categories: The first works that were well received, even by his most fervent enemies. Those he would not reject. The second included writings that attacked the abuses, lies, and desolation of the Christian world and the Papacy in particular. “I cannot reject these—for to do so would allow these abuses to continue. Were I to retract them, then the door is only open to further oppression. If I recant these—then I am only strengthening tyranny.” The third category of writings primarily attacked individuals. “I apologize for the harsh tones contained within, but I do not reject the substance of what is within.” Luther concluded his defense simply: “If there is scripture that shows my writings in error—then show me. I would gladly reject them. Unless I am convinced by the testimony of the scriptures or by clear reason, for I do not trust in the Pope or church councils alone; is it well known that they have erred and often contradicted themselves. I am bound by scriptures I have quoted and my conscience is captive by the word of God. I cannot and will not recant anything since it is neither safe nor right to go against conscience. Here I stand—for I cannot do otherwise. May God help me. Amen.”

Johann von Eck was quick to move onto the attack: “Martin—there is no one of the heresies which have torn he bosom of the church, which has not derived its origin from the various interpretations of the Scripture. The Bible itself is the arsenal whence each innovator has drawn his deceptive arguments. It was with biblical texts that Pelagius and Arius maintained their doctrines; Arius, for instance, found the negation of the eternity of the Word—an eternity which you admit, in this verse of the New Testament—Joseph knew not his wife till she had brought forth her first-born son; and he said, in the same way that you say, that this passage enchained him. When the fathers of the Council of Constance condemned this proposition of John Hus—The church of Jesus Christ is only the community of the elect, they condemned an error; for the church, like a good mother, embraces within her arms all who bear the name of Christian, all who are called to enjoy the Celestial beatitude.”

The diet was soon forced to break into private conferences, while discussions were held to determine Luther’s fate—but he was not arrested at Worms, and was able to leave, owing to the letter of safe conduct that the Elector of Saxony had obtained from him. Fearing for Luther’s safety, the elector took the extraordinary step of sending men to fake a highway attack upon Luther—with orders that he should be abducted and brought to safety at Wartberg castle, where he would soon be hidden away. In May, Charles V promulgated the Edict of Worms with support from the diet. Luther was condemned as a notorious heretic, and citizens were forbidden from propagating his ideas.

Last edited:

Yay for Ferdinand being cleared! And has Charles found out his son is missing or is it too early yet?

The discovery that Philip was missing occurred in January of 1521, so around the time the Diet of Worms was opening.Yay for Ferdinand being cleared! And has Charles found out his son is missing or is it too early yet?

I'd say Charles and Mary don't know yet... but will shortly. The news would certainly reach the emperor in a matter of weeks if it was sent off, but I imagine the Castilian regents are doing some investigating; if Philip is gone, better to investigate and have an answer for the emperor: that his son was killed or sickened, not that he just simply vanished.

Given the delicate situation in the diet, there also may be those wanting to hold back such delicate information until the time is right... especially if the empress may be expecting again (Mary's coronation chapter mentions a birth of a daughter the year before, so in 1521).

Nice to see that things are moving ahead and that Mary and Margaret have Burgundy under control. Mary must be thrilled to be out of Spain really.

There is something I’m wondering about though:

There is something I’m wondering about though:

I am wondering whether Wolsey would be as succesful here without Henry VIII. Given his pro-French attitudes, I am unsure whether Catherine would allow his advancements to the same degree that Henry did. I also think that she wasn’t fond of him, but I must admit that the notion could be coloured by tv shows here. Henry died in 1513, so Wolsey was never appointed Royal Chancellor by him and perhaps he never became Bishop of Lincoln and Archbishop of York in 1514. I certainly have less belief that Catherine would allow him being bishop of both. This also means that Leo X might not have appointed him Cardinal on 1515 and papal legate to England in 1518 (I would imagine that Henry would campaign harder for that than Cat and if he isn’t bishop of anything then it is even less unlikely) and he also would not be abbot and bishop of Bath in 1518. Certainly he would not also become bishop of Durham in 1523 and of Winchester in 1528. My point is, with Henry dying in 1513, I imagine that Wolsey’s career would take quite a different turn and he would advance slower and not to such great heights. Especially with trusting and careless Henry being replaced by skeptic and pious Catherine who would be much less invested in seeing him advance and who would likely (I think) tolerate the church office abuses much less. Warham and Foxe might also stay around a bit longer, although I seem to recall that you had Catherine appoint More as Royal Chancellor? Compton also isn’t beheaded (which I admit is a very small butterfly)Charles took the chance of his time at Mechlen to hold an interview with England’s longtime ambassador in the Low Countries, Thomas Boleyn—where Charles provided the ambassador with several letters—one to be passed on to his aunt, the queen-regent: and another to be given forward to Cardinal Wolsey. Charles’ letter to his aunt outlined the mutual interests that lie between both kingdoms, and that with the ceaseless ambitions of the French King, they ought to band together in mutual alliance. The king’s letter to Wolsey was more coded—in it, Charles made plain that he knew of the Cardinal’s great friendship with France. He played on the Cardinal’s vanity, writing: “My very good friend—your abilities are too great to be wasted simply as a minister amongst many; there are greater roles that you could play within our Holy Church—as I am sure you are all too aware of. Accept my friendship, and spurn that of France—and I shall help you however I can.” The king also promised Wolsey a pension of 7000 ducats.

Last edited:

You do make some good points, but to be fair, Wolsey had already cemented a bit of influence by 1513 within the royal household, and proved himself very well in his management and supply of the English troops as almoner during Henry VIII's sojourn abroad, and likely played a role in ensuring their orderly return, ensuring that the English army sent to France in 1513 wasn't completely wiped out, and that the king's body could be returned home and not submitted to indignities that the French might impose. In such a situation, I think Wolsey would gain the queen's appreciation, though certainly not her love.Nice to see that things are moving ahead and that Mary and Margaret have Burgundy under control. Mary must be thrilled to be out of Spain really.

There is something I’m wondering about though:

I am wondering whether Wolsey would be as succesful here without Henry VIII. Given his pro-French attitudes, I am unsure whether Catherine would allow his advancements to the same degree that Henry did. I also think that she wasn’t fond of him, but I must admit that the notion could be coloured by tv shows here. Henry died in 1513, so Wolsey was never appointed Royal Chancellor by him and perhaps he never became Bishop of Lincoln and Archbishop of York in 1514. I certainly have less belief that Catherine would allow him being bishop of both. This also means that Leo X might not have appointed him Cardinal on 1515 and papal legate to England in 1518 (I would imagine that Henry would campaign harder for that than Cat and if he isn’t bishop of anything then it is even less unlikely) and he also would not be abbot and bishop of Bath in 1518. Certainly he would not also become bishop of Durham in 1523 and of Winchester in 1528. My point is, with Henry dying in 1513, I imagine that Wolsey’s career would take quite a different turn and he would advance slower and not to such great heights. Especially with trusting and careless Henry being replaced by skeptic and pious Catherine who would be much less invested in seeing him advance and who would likely (I think) tolerate the church office abuses much less. Warham and Foxe might also stay around a bit longer, although I seem to recall that you had Catherine appoint More as Royal Chancellor? Compton also isn’t beheaded (which I admit is a very small butterfly)

As for Catherine and Wolsey's relationship.... in OTL, it's hard to discern what their relationship was like c. 1513. Obviously, she did not like his pro-French policies, and preferred to be aligned closer to her nephew. But Wolsey was also a very fair weather friend, and had no issue supporting a Spanish foreign policy if it suited him. Most of the sour parts of their relationship came later on, during the king's matter. In this situation, I like to think that Catherine has an attitude towards Wolsey that could be described as similar to the relationship that Louis XIII had with Cardinal Richelieu very early on: she doesn't necessarily trust him, but she does recognize that he possesses a certain aptitude for government, and such a man is better to retain within her councils, rather than send him outside of it, Especially in the uncertain times of England's first reigning queen.

I imagine that his promotion to Lincoln, followed by York were due likely to his assistance in ensuring the king's body was bought home, and Catherine being grateful for that. He would not hold said Bishoprics co-currently, and there might be a span of time between them. Or perhaps he receives only Lincoln and the Cardinal's hat? York is a rather important benefice, the second most important.

Right now, his position is thus: he sits on the privy council, with a focus on foreign affairs; he holds the Archbishopric of York, and he is a Cardinal. He doesn't possess any further titles or Bishoprics. He certainly doesn't have the dazzling wealth that his OTL counterpart possesses, he has not built Hampton Court nor expanded York Place, what would later become Whitehall. There is perhaps a part of him that realizes that he is career has stagnated in England and might go no further. He's comfortable, but this is not the man who possesses the untold influence of OTL.

As for Catherine's council, she has retained both Warham and Foxe in the positions they occupied in 1513. She certainly favors the nobility and high churchmen over "new men" such as Wolsey, hence men like Brandon being pushed totally aside and being forced to go abroad, while William Compton is probably stewing on his country estates. Thomas More is a close friend of the queen, and his books have been used in educating young Queen Mary, but he does not have a place on her council.

Last edited:

@DrakeRlugia you make some valid points. Bishop of Lincoln I can see and maybe also him being promoted to York afterwards, but I’m still uncertain about the cardinal hat - But if you want it in the tl then that’s entirely fair

Hopefully More and Catherine won’t be too zealous in their pursuit of the Protestants

Hopefully More and Catherine won’t be too zealous in their pursuit of the Protestants

And cool coolAs for Catherine's council, she has retained both Warham and Foxe in the positions they occupied in 1513. She certainly favors the nobility and high churchmen over "new men" such as Wolsey, hence men like Brandon being pushed totally aside and being forced to go abroad, while William Compton is probably stewing on his country estates. Thomas More is a close friend of the queen, and his books have been used in educating young Queen Mary, but he does not have a place on her council.

Good chapter as always, hopefully Luther can keep the Protestant movement going strong like OTL and that the papacy can reform to combat them

I mostly want him to have the cardinal's hat so he has a clearer connection to the church and curia. With his career stagnant in England, I'm thinking perhaps he might debate transferring his career completely towards the Church and the Papacy; that is primarily what the emperor is offering to assist in. He doesn't have the influence at this point consider standing for election, but an ambitious man is still ambitious and might see the Holy Father as a better employer...@DrakeRlugia you make some valid points. Bishop of Lincoln I can see and maybe also him being promoted to York afterwards, but I’m still uncertain about the cardinal hat - But if you want it in the tl then that’s entirely fair

And cool coolHopefully More and Catherine won’t be too zealous in their pursuit of the Protestants

Certainly the writings will likely become popular in England as well, given England has her own history of reform movements, such as the Lollards. But Catherine would all too aware of the state of the Spanish church prior to her parents reforms, and More is connected to the Humanist school that while quite Catholic, realized that the church had issues and flaws.

At this point, things are likely to march onward. Luther has powerful patrons, and the emperor lacks the funds and the troops to combat that.Good chapter as always, hopefully Luther can keep the Protestant movement going strong like OTL and that the papacy can reform to combat them

This has mostly been as OTL. I debated having the Diet of Worms turn out differently, but it was likely that Luther would've been allowed to leave unimpeded regardless, given his patron in Saxony. Arresting him and murdering him just would've inflamed matters, IMO... though matters are probably to get inflamed, regardless.Have there been any major changes to the Reformation yet, or is this mainly stage-setting before the butterflies start flapping? I was raised Lutheran so you’d think I would know this already 🫣

The emperor could certainly help him in getting a cardinal’s hat if neededI mostly want him to have the cardinal's hat so he has a clearer connection to the church and curia. With his career stagnant in England, I'm thinking perhaps he might debate transferring his career completely towards the Church and the Papacy; that is primarily what the emperor is offering to assist in. He doesn't have the influence at this point consider standing for election, but an ambitious man is still ambitious and might see the Holy Father as a better employer...

That's a good idea, too. I think I'll adjust the chapter to reflect that. He's merely Bishop of Lincoln, then.The emperor could certainly help him in getting a cardinal’s hat if needed

Charles does not really lack funds by having Burgundy, but the issue of troops can hold him back until he gathers allies within the Empire. Regarding the expansion of Protestantism, I see it likely that it will be contained in Scandinavia and Northern Germany while England remains officially Catholic under its own national church but still with a large Protestant minority.the emperor lacks the funds and the troops to combat that.

Honestly given how Protestantism involved things like the taking of land and wealth of the Church as well as centralization in a way, it does make me wonder if maybe France doesn't go Protestant here, take the place of Britain as the premier Protestantism powerCharles does not really lack funds by having Burgundy, but the issue of troops can hold him back until he gathers allies within the Empire. Regarding the expansion of Protestantism, I see it likely that it will be contained in Scandinavia and Northern Germany while England remains officially Catholic under its own national church but still with a large Protestant minority.

This is true, but Charles' finances have been very badly stretched by his election as emperor. The amount of bribes he's had to extend have been quite immense, and he's had to contract loans from the Fuggers, as well. You do have some interesting thoughts regarding Protestantism though: it could end up much more confined compared to our world.Charles does not really lack funds by having Burgundy, but the issue of troops can hold him back until he gathers allies within the Empire. Regarding the expansion of Protestantism, I see it likely that it will be contained in Scandinavia and Northern Germany while England remains officially Catholic under its own national church but still with a large Protestant minority.

One thing to remember is that the French crown already had a bit of sway over the Catholic Church in France. The Concordat of Bologna already gave the crown pretty large sway over the appointment of benefices, and while the church was once more allowed to collect incomes within France (this had been forbidden by the Pragmatic Sanction of Bourges back in 1438), the king was allowed to collect tithes from the clergy and continued to restrict their ability to appeal to Rome. Still, the Concordat was a step down from the previous Pragmatic Sanction and encountered opposition from the Parlement of Paris. Francis was fairly friendly to the reformers until ~1530, and he certainly saw the Protestant princes as allies against the emperor. So, it wouldn't be completely out of pocket...Honestly given how Protestantism involved things like the taking of land and wealth of the Church as well as centralization in a way, it does make me wonder if maybe France doesn't go Protestant here, take the place of Britain as the premier Protestantism power

Chapter 14. An Emperor’s Folly – The Italian War of 1521-1526

So sorry for the delay, guys! This chapter was a doozy. Wanted to cover more than the span of a year or two, and well... it ended up taking me over a week to write. I'm very proud of this, especially the twist at the end. Hope everyone enjoys, and can't wait to hear everyone's thoughts.

Chapter 14. An Emperor’s Folly – The Italian War of 1521-1526

1521-1526 – France, Germany, Italy & Spain.

“My cousin François and I are in perfect accord – he wants Milan, and so do I.”

— Emperor Charles V

Music Accompaniment: Contre Raison (Gaillarde)

The Battle of Lodi: The Ultimate Battle of the Italian War of 1521.

Though Europe had enjoyed relative peace after the War of the League of Cambrai—it had not solved any of the issues that continued to fester. France still ruled over the Duchy of Milan, with King François eager to exert his influence further: very few could forget that French crown had also laid claim to the Kingdom of Naples in the reigns of Louis XII and Charles VIII, and that François might attempt the same. There was also the growing rivalry between France and Spain—in the persons of King François and Emperor Charles V. While the Imperial Election of 1519, which had resulted in the election of Charles V as emperor had contributed to tensions between France and Spain, there also remained the outstanding issue of Navarre—while Spain held Upper Navarre, south of the Pyrenees, the Kingdom of Navarre remained alive and well in Lower Navarre. While the Treaty of Noyon signed in 1516 between France and Spain had contained provisions to deal with the Navarrese issue, they had proved ineffectual—and the issue of Navarre remained a thorny wedge between the two issues.

With Charles’ coronation at Aachen in the fall of 1520, along with the provisions to raise an army for the emperor’s coronation in Rome, French fears were heightened. Did the emperor wish to be crowned as his grandfather had not? So be it; but let him come with a retinue—not an army at his back, which would no doubt threaten French interests in Milan—and perhaps provoke another uprising against French rule in Italy. François decided that he needed to make a preemptive blow—and with plausible deniability. François planned to strike at Charles from both the north and south—he employed Robert of La Marck, the Duke of Bouillion, to attack Luxembourg with Black Band, a group of Landsknechts who had long been in the service of France; in return, Robert of La Marck was be given a French pension. In the south, François provided liberal funding and troops to King Henri II of Navarre to reclaim the pieces of his kingdom that had been lost. “The king was determined to give the emperor a bloody nose,” The Sieur de Malaspine wrote in his celebrated memoirs. “And so, he prepared to push the emperor to war by using others to complete his dirty business.” While Henri II of Navarre was nominally at the head of the Franco-Navarrese army, it was effectively commanded by André de Foix. The French battle plans proved flawed; Henry of Nassau was able to effortlessly push back the French offensive aimed at Luxembourg. The Franco-Navarrese offensive proved more successful, with the French invasion into Upper Navarre provoking an uprising amongst the Navarrese who had long tired of Spanish domination. With the troops garrisoning Navarre being used in dealing with the revolt of the communities, the Franco-Navarrese army was able to easily seize Pamplona—the capital of Navarre fell after a short siege of three days, and within three weeks, the majority of Upper Navarre was once more under control of the Kingdom of Navarre. From Pamplona, André de Foix was able to make forays into Castile across the Ebro—raiding Logroño, where several vital pieces of artillery were seized. The invasion of the Franco-Navarrese forces served to help push the moderate comuneros to seek reconciliation with the royalist party.

While François watched with glee as his troops helped add fuel to the fire in Spain, Charles was busy making his own moves. The specter of Luther had served to help unite the emperor and the pope in a common cause; Leo X, knowing he would need imperial support, was willing to abandon any pretension of friendship with France, and was prepared to assist in expelling the French from Milan—with the promise that Parma and Piacenza should be given to the Papacy. Charles’ diplomatic overtures with his aunt in England bore fruit as well; the Treaty of Gravelines was signed in the fall of 1521, with England renewing its alliance with the emperor. Catherine once more agreed to provide her nephew with funds: this time, a loan of £55,000 with the proceeds to be raised through a benevolence or forced loan; the emperor in return agreed to repay the English loans with interest—and to make a gift of 250,000 ducats Queen Mary’s future dowry. Catherine also agreed to supply the emperor with a troop of 5000 men, which would be raised under the command of Thomas Howard, the Earl of Surrey—to serve the emperor where he pleased. Catherine also undertook that England prepare an army to invade France within the year. François in turn, was plotting his own diplomatic moves: he received reassurances from the Republic of Venice that were prepared to support the French position in Milan, while the Duke of Albany—enroute to return to Scotland after a sojourn of several years in both France and Italy, once more reaffirmed his support and alliance with the French—granting the regent a detachtment of men to take with him to Scotland, along with powder and shot. He also granted the Scottish regent a disbursement from the royal treasury of 40,000₶. Should England dare to meddle in this conflict between giants, François was fully prepared to fully unleash his Scottish dog upon them—whatever the cost.

Diplomatic options were exhausted in the fall of 1521—Charles demanded not only recompense for the raid on Luxembourg, but that French troops supporting the King of Navarre should be vacated from those occupied territories. François was intransigent—he stated through his envoys that he had no dealings with the renegade Duke of Bouillion and the raid on Luxembourg, nor could he control what the King of Navarre, a rash young man, wished to do with his own rag-tag group of Gascons. François suggested in turn that Upper Navarre should be returned to Navarrese sovereignty, as had been promised at Noyon. Catherine of Aragon in turn offered her services as a mediator—with the King of France snapping his fingers at such an offer. “This Spanish bitch! The so-called regent of England believes herself impartial enough to judge in this situation,” François is said to have remarked. “She is her father’s daughter—and cannot be trusted. A pitiful woman of no standard. I would rather entrust my fate to Lady Fortuna upon the battlefield, than to trust the Spanish harpy. She is the emperor’s lapdog; but she should beware, for France has its own cur in Scotland—try us, O Lady, and Scotland will scratch and bite harder than you could ever imagine! What help can you rend to your precious nephew then?” The die was soon cast—and Imperial troops under Henry of Nassau soon invaded northern France. They had little issue overrunning several border towns—but found resistance at Mézières, where the Lord of Bayard valiantly held the city—allowing King François time to raise fresh troops at Reims to counter Nassau’s invasion. Nassau unleashed a fury of artillery fire upon the city, reducing it to rubble; with French troops approaching, the weather turning colder, Nassau decided it more prudent to withdraw back towards the Low Countries for winter quarters. “Leave no stone unturned, no crop unburnt,” Was Nassau’s order to his troops as they retreated north—leaving towns and villages in waste as he pulled north. The Franco-Navarrese force continued unimpeded within Navarre—the citadel of Amaiur capitulated in October of 1521, while Louis of Lorraine assisted in taking the town of Fuenterrabia. It was during this time that cracks began to appear in the relationship between the King of France and one of his closest (and most powerful) kinsmen, the Duke of Bourbon, also known as the Constable of Bourbon—when François named his brother-in-law, the Duke of Alençon as commander of the vanguard of the French army raised at Reims—a position that by right belonged to the Duke of Bourbon.

Cardinal Pompeo Colonna was elected Pope in 1522 as Pope Pius IV.

In Italy, the French governor of Milan, the Viscount of Lautrec, was ordered to defend his position as best he could against both imperial and papal forces; Charles V had not only ordered Spanish troops under Ferdinand d’Ávalos north from Naples but had sent forces from Germany to assist the Papal army under Prospero Colonna. Lautrec on his side had Swiss mercenaries, as well as troops from the Venetian Republic. Finding his position within Milan untenable, Lautrec soon abandoned the city to take up a more defensive position along the Adda River. With his superior artillery, Lautrec prepared for take up his winter quarters at Bruzzano—protecting his position and holding the joint troops of the pope and the emperor from pressing further towards Genoa. “I am in most dire need of funds,” Lautrec wrote to the king that winter. “The Swiss are near mutinous; they are demanding either to be paid, or that we attack…” The issue would have to be dealt with, come spring—or serious consequences would likely ensue. The winter of 1521 also saw the death of Pope Leo X—the resulting conclave held at the end of 1521 into January 1522 saw wrangling between both the imperial and French factions—with both France and Spain dispersing huge bribes to their favored candidates. In the end, Cardinal Pompeo Colonna was elected Pope, taking the name of Pius IV. Pope Pius IV favored a continued alliance with the emperor—but above all, to see the French fully ejected from Italy.

In the spring of 1522, fighting immediately resumed. Lautrec found himself forced to commit to a pitched fight at the Battle of Burzzano, the Swiss troops charged against the Spanish and German lines, giving the French artillery no chance to work their magic; the Swiss troops were utterly shredded and would soon decamp to their cantons, forcing Lautrec to retreat towards France. Lombardy was soon excised of its French tumor, and in the summer, Genoa fell after a brief siege. The emperor, still facing heavy pressure from the French in Navarre, was ultimately forced to make peace with the moderate rebels in Castile, resulting in the Treaty of Segovia. With both sides united in crushing the more radical revolutionaries, it also freed up Spanish troops to prepare for an offensive. It was in the summer of 1522 that the emperor learned the fate of his son and heir. “My darling,” A letter from the emperor to the empress begins, dated in late May of 1522. “Since our lord, who gave Philip to us, wished to have him back, we must bend to His will and thank Him and beg Him to protect what is left. With great affection, my lady—I beg you to do this and to forget and leave behind all pain and grief.” The emperor had no answers for what happened—only that it had. While the emperor bore the news stoically, putting his faith in God, the empress was beside herself at the loss—she was said to have wept bitterly, remarking to her ladies that: “Spain, dreadful Spain—it has killed my darling Philip; they can say he has sickened and that it is God’s will…but so long as I live, I shall never believe it. My own son, my first born—I did not know him during his short life, as I was forced to leave him behind… and now I never shall. I know the truth. My son was murdered by ambition; I shall curse Spain for the rest of my days; I swear revenge on those who have robbed me of my eldest son.” As the news of Prince Philip’s disappearance and death spread, some whispered of a Tudor Curse—had not Henry VII came to the throne of England by slewing the usurper, Richard III—who had climbed onto the blood-soaked throne through his pitiful nephews? Some murmured that perhaps Henry VII—had played a larger role in the matter, and as such, his descendants would be doomed to tragedy. A farce—but an interesting farce whose story spread. Some feared for Empress Mary’s health following the revelation of Prince Philip—she received the news when she was pregnant and was so swept up in grief that her servants truly feared for her demise. She persevered: her daughter Mary, to be known within the family as Marie was born without issue in 1522. In France, similar concerns pervaded the court regarding Queen Claude—pregnant for the eighth time, and in failing health. Claude died giving birth to a young prince—the queen asked that the young prince be named Louis with her dying breath—in honor of her late father, Louis XII.

Queen Claude, c. 1520; She died at her post, giving birth to her eighth and final child, Prince Louis.

Negotiations between the royalists and moderate rebels allowed some semblance of authority to be restored to central Castile—and Iñigo Férnandez, the Constable of Castile, was able to cobble together an army of some 30,000 that would finally offer some concrete resistance against the French invasion in Navarre. With Spanish troops moving northward, André de Foix was forced to retreat beyond the Ebro—with the Spanish laying siege to the major fortifications at Fuenterrabia which would allow them to surround the French forces in Upper Navarre completely. André de Foix wrote pensively to the King of Navarre, stating: “Our position has faltered compared to last year; our advantages are rapidly depleting. Your subjects lose faith by the hour; make an appearance, and all shall be well.” Henri II remained safe and sound in France at the Château de Pau; he refused to render André de Foix any financial aid, fearing the expedition was turning sour. Spanish troops continued to move slowly against the French positions in Spain throughout 1523, taking back Fuenterrabia as well as seizing both Estella and Olite—placing Pamplona under direct threat. With the armies of Charles V beginning to gain ground, England fulfilled its end of the bargain with the emperor—in May of 1523, England declared war of France. It immediately committed some 15,000 troops into the field, under the command of the Earl of Oxford. With the French stretched thin by Imperial attack, the Earl of Oxford was able to act with impunity as his army marched out of Calais and into Picardy—with the French unable to mount an effective resistance as Oxford plundered and razed the fields around Abbeville, before crossing the Somme River. Though the English offensive came within distance of Amiens and likely could’ve pushed towards Paris, the lack of artillery and supplies—as well as reinforcements from the emperor meant that Oxford was soon forced to withdraw back towards Calais—arriving there in December of 1523.

In Scotland, England’s push into the conflict against France and Albany’s desire to aid his French allies prompted a tumult. Albany’s control over the regency of Scotland had slackened during his sojourn to France and Italy, where he had mainly relied upon his lieutenants to excise authority in his name. While Albany returned to Scotland imbued with confidence that French money and arms provided, he did not realize that his languid regency had caused great strife amongst the kingdom—people were hungry, there was no justice—and they did not believe that the Duke of Albany cared for their king. Alexander IV, now nine—had spent most of his time since Albany’s absence under the strict care of Albany’s appointees, who reigned over the royal household like little lordlings, with the king closely confined at Sterling Castle, ostensibly for his own protection. This unrest against the malaise of the regency empowered the anti-Albanist party, which received ready support in great secrecy from England. The enemies of the regent also had a secret weapon: the queen dowager, Margaret: still at Doune Castle—where she had languished for six years, protesting her innocence. The regency had offered to free the queen on the condition that she recant her story regarding Albany’s proposal of marriage and admit that she was a liar. The queen, haughty as any Tudor retorted to her goalers: “I cannot admit to a lie which is the truth. I shall always state it is the truth, until the day I die. I curse Albany—he shall never get from me those words which might heal his reputation. Nay, never. I shall never submit, and if I am kept here, then so be it. I shall only leave Doune by a coffin, never a horse, so long as Albany reigns.”

Soon after Margaret’s famous words, the anti-Albanist party led a raid on Doune Castle, freeing the queen from her confinement. “Who dares come into a lady’s house as such, with your armor and sword drawn?” Margaret was reputed to have said as she met with her liberators—or perhaps new jailers in the great hall. At this, the men kneeled before her, starting with the man who had led the daring attack—James Hamilton, the Earl of Arran. “We are your true friends, madam,” Hamilton is recorded as saying. “We come not only to free you—but to restore you to your rightful position as mother of the king. The uncle has failed; you—with our help, must steady the ship of state.” Though Margaret was pleased to be freed, and would happily go forth, she made one request from her new allies: that she would not leave Doune as a liar. This the anti-Albanists were happy to aid her in this, for it served their purposes. Along with news of Margaret’s liberation, enemies of the Duke of Albany also publicized what they claimed to be a genuine marriage contract between the Duke of Albany and Queen Margaret—dated March of 1516, at the height of their affair. Albany’s supporters denounced the document as a sham and forgery; his enemies saw it as a genuine document. In due course, the Earl of Arran’s troops had little difficulty in taking control of Sterling and taking control of the young king’s person—with Alexander IV being returned to the custody of his mother, who he had not seen since 1516. Arran and Albany’s forces clashed at the Battle of Whitecross in November of 1523—resulting in the scattering of Albany’s troops and his overthrow from the regency. By December, the Duke of Albany fled into exile in France, with the Earl of Arran restoring Queen Margaret to the regency—with Arran assuming the title of chancellor. Other allies of Arran, such as the Earls of Argyll, Eglinton, Lennox, and Montrose were favorably rewarded with choice positions upon the council and within the royal household. Queen Margaret—with her son, the young king, at her side, would return in triumph Edinburgh—with the royal court taking up residence at Linlithgow Palace.

Arms of the Earl of Arran: One of the Five Earls, and Queen Margaret's newest ally.