Chapter 30. The Lady of Paris

1540-1542; France, Italy & Navarre.

“Stronger faith than was ever sworn,

Prince again, oh my only princess,

That my love, which will be to you ceaselessly

Against time & assured death.”

— Vers à Isabelle, written by the Dauphin François for his wife.

Music Accompaniment: Pavane de la Guerre

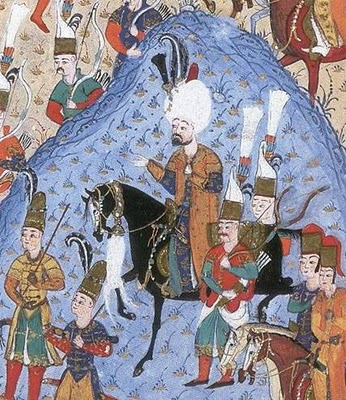

King François of France, c. 1530; French School.

The

Truce of Lucca signed in 1539 restored peace between the Houses of Valois and Habsburg but effected no real change in the makeup of Italy. King François continued to hold the Duchy of Milan, just as his ally Louis IV held the crown of Naples. Though peace now reigned between France and the empire, François kept his troops in Savoy. He refused to return it to Charles III—a known partisan of Emperor Charles V who had married the emperor’s sister, Catherine of Austria.

“So long as I live and breathe, Savoy shall remain under my dominion,” François declared before his marshals—making his point clear. Charles III, his wife, and numerous children now languished in exile in Brussels hoping they might one day be allowed to return to their domains. François appointed the Marquis of Saluzzo as governor of Savoy, and introduced garrison troops into Turin to ensure the duchy remained sedate. Though François had not been victorious in the previous conflict, his position in Italy had vastly improved in some ways.

Through the 1530s, François continued to reign as a humanist—the ideal Renaissance prince. He formally declared French as the official language of the kingdom and provided funding for the creation of the

Collège Royal where students could study French alongside Greek, Hebrew, Aramaic, and even Arabic. François pursued a policy within France to eradicate Latin as the language of administration—an ordinance published in 1539 at Villers-Cotterêts established French as the administrative language of the kingdom. It also mandated that priests record births, marriages, and deaths, and ordered the formation of registry offices in each parish. The ordinance did not apply to the Duchy of Milan, where François ordered the Governor of Milan to carry out a similar reform through the

Ordinance of Lecco that formally established Italian as the official language of the duchy and sought to simplify the administration there as well. France’s economy continued to grow throughout the period—François offered subsidies and tax exemptions to lure Milanese weavers to Tours and Lyons to bolster France’s silk industry. François paid attention to military industries especially—he encouraged the growth of foundries in northern France to produce muskets and artillery for his growing army, and he ordered extra funds expended to renovate and expand the harbors of Rouen, Toulon, and La Rochelle.

Religious issues continued to remain complicated within France. The Council of Bologna closed in Italy without accomplishing any real work, and Pius V expressed little interest in moving forward with another council until other sovereigns agreed.

“While we value your opinion—and that of France as the eldest daughter of our church,” Pius V wrote in a candid letter to François.

“A council will require support from all of Catholic Europe… until the emperor and the Queen of England, among others, support our cause, I believe it is futile…” The divide between Protestants and Catholics continued to grow—and in France, the ideas of the Protestants continued to intrigue the commercial classes in the large cities, and members of the high nobility, too. François’ sister, Marguerite, the Queen of Navarre, was an ardent reformist and was friendly with Marie Dentière, a Protestant reformer who encouraged Marguerite to turn her brother away from the Catholic church. Anne de Boullan, the Duchess of Plaisance and mistress to the King of France was also a believer in the religious reformation, with Anne sharing a close connection with Marguerite. The position of the king’s sister and mistress supporting religious reform was juxtaposed with the ardent Catholicism of his wife, Beatriz. Though François had always remained lenient towards the Protestant cause and never begrudged the beliefs of those whom he adored, his beliefs hardened against the Protestants in the late 1530s following the

Affair des Placards, when anonymous French reformists plastered placards denouncing the mass across Paris and other provincial cities, as well as upon the doors of the king's bedchamber.

Prosecution of Protestants in the reign of François I; Late 1530s.

“There is no doubt that Madame Gouttières is behind these foul posters,” Queen Beatriz wrote in an impassioned letter to her sister—a veiled reference to Anne de Boullan contained within it.

“She has stolen the king from me, and I do not doubt that she shall not rest until she has converted him to her faith. He is utterly bewitched… I know not what to do.” Many believed that Anne—and perhaps Marguerite—had some connection with the placards. Others pointed fingers at French reformers, such as Antoine de Marcourt were the true suspects given the placard's Zwinglian wordings. François countered the placards by ordering processions through each of Paris’ parishes. The king himself attended, with one onlooker writing,

“The king and the queen stood under a canopy dyed a most magnificent azure blue—fleur-de-lys etched in golden silk thread. Their majesties stood solemn and silent as the Most Holy Eucharist was carried before them, making clear where the king stood.” The king’s affirmation of his Catholic faith provoked the first clamp down on the Protestant religion in France; some of France’s most prominent Protestants would go abroad, such as Jean Calvin who settled in Geneva, and Clément Marot, who entered the service of Empress Renée. Though François made no break from Anne de Boullan—he made clear that his conscience remained where it had first sprung, and no polemics from her or from his sister would sway his opinion.

In truth, the relationship between the Duchess of Plaisance and François began to cool down. Following the triumphant birth of her son, Octave, Anne rode upon a wave of infamy. In 1535, Queen Beatriz finally gave birth to the son she had desired for so many years:

Philippe Emmanuel. The young prince would become Duke of Orléans and second in line for the throne following the death of his older brother, Louis, in 1538. Though Anne became pregnant in 1536, this pregnancy did not progress as smoothly as the others.

“Daily the duchess complains of aches and pains… she is in great agony, and suffers from a terrible malaise,” one of Anne’s ladies, Yolande de Sèvre wrote in a furtive letter to her aunt.

“She is recently enceinte again… but I swear I have never seen my lady so unwell. The chamber femmes gossip as always; they claim that the queen’s Portuguese valet, Fernão de Castro has no doubt slipped something into one of her drinks…” These rumors did not fade. Though Anne would recover, she suffered a miscarriage when she fell down a flight of stairs at Amboise during her seventh month of pregnancy. Anne gave birth to a stillborn daughter whom she named

Marguerite. Anne’s final pregnancy would be in 1540—and she gave birth to a stillborn son that she called

Charles-Hercule.

“… I must write with heavy regret, sire, that we have lost the child—though the duchess fares well, and we believe she shall survive,” one of François’ royal physicians wrote to him in the aftermath of Anne’s final pregnancy.

“… but I must be frank, majesty: the lady has suffered gravely in your service and has been wounded… this final travail has caused much damage. Though the duchess shall be fit for service soon, I must make clear that further pregnancies would be at risk to her life…” Thus began the transformation of Anne de Boullan from the king’s mistress into his greatest friend. The bond of physical love was shattered in 1540, but Anne’s influence would only grow.

Despite Anne now being heralded as the king’s friend, it did not lead to an improvement in the relationship between François and Beatriz. François led a separate life from his consort. While he saw her on formal occasions and occasionally slept with her out of duty, François had long tired of her dramatics and hysterics—no longer did they fight and soon makeup soon after in the bedchamber. Beatriz gave birth to her final child in 1542—a daughter named

Marie in honor of her mother, Maria of Aragon. Beatriz doted upon both of the children, with the Governess of the Children of France lamenting in a letter to the king that:

“… though, of course, I welcome the queen to visit the nursery and see to the children, I lament that she feels the need to criticize about how the nursery is arranged… surely, the queen should not deign to bother with such matters?” The birth of her children provided a needed balm for Beatriz—she did not get along well with her stepchildren, and her own children gave her a much-needed outlet for her maternal feelings.

“Though the queen would rage as that was her way,” one courtier wrote in their memoirs.

“The queen calmed considerably following the birth of Madame Marie.” The division of the court between the king’s mistress and his wife leaked into the royal family—François’ children from his first marriage adored Anne de Boullan and despised Queen Beatriz. In turn, Beatriz’s children would soon grow up to adore their mother and to despise the mistress who had stolen their father. Even as Anne left behind her physical relationship with the King of France, she ensured that the king’s was satisfied by supplying him with a retinue of women who could take care of his needs—and leaving soon after. These women were kept at homes near the French court that the Duchess of Plaisance called her

petit jardins.

“Pure filth, she has stooped to her lowest levels, no better than a common harlot,” one critic of Anne announced in a letter to a friend.

“How can one be expected to pay allegiance to such a frightful creature?”

King François as Saint John the Baptist; 1520.

François also spent the latter part of the decade seeking martial alliances for his eldest daughters. Charlotte—previously discussed—married Alexander, the King of Scots, while Louise, the sister spurned by Scotland married Louis IV of Naples. For the youngest of the older princesses, Anne, marriage was not something she had ever had in mind. Compared to her more robust sisters, Anne had always suffered from ill health.

“Our little princess has been diagnosed with the pox,” a member of the royal nursery wrote in a letter to their family.

“… the royal doctors despair her survival.” The young princess was struck with smallpox in 1527; though she recovered, she was left blind in one eye and with scarring across her hands and cheeks. Anne, rather than despair over her fate, found solace in religion and declared her wish to enter religious life. François was reluctant to grant his little nun her wish, as part of him nursed hopes that he still might find a suitable marriage for her.

“His Majesty, of course, had no desire to see his daughter enter a convent,” Claude d’Urfé wrote in his private journals.

“…though he was a good and sincere Catholic, he did not wish to see one of his daughters waste away in a religious vocation when there was so much more he could offer them…” Only after Anne’s twentieth birthday in 1538—when the king felt that he would be unable to find Anne a suitable husband did he finally relent and agreed that she could take on a religious vocation.

“Madame Anne’s adoption of her new vocation was carried out in the utmost secrecy…” a lady of Princess Anne’s suite wrote in a letter home.

“… the king's approval came late one evening—and none knew except Anne herself. She departed from Fontainebleau accompanied by one of her ladies and a small guard. When dawn rose over the court the next morning, the princess was gone… a week later, we received news that she had been allowed to embrace her religious calling… she took up residence at the Abbey of Saint-Pierre-les-Dames, in Reims…” The entrance of a royal princess into the abbey gave it access to much needed funds through Anne's royal dowry; a royal princess residing in the convent also attracted numerous outside donations. In 1542, Anne would become abbess of the abbey. The youngest of François’ daughters with Claude, Victoire would marry relatively late at the age of nineteen in 1540 to Wilhelm, the Duke of Jülich-Cleves-Berg—as part of François seeking alliances with likeminded German princes.

In Italy, François pursued a conciliary policy among the Italian princes. With the emperor’s failure to triumph even after his finances and domains recovered, many of Italy began to wonder how long French domination over the peninsula might continue. Pope Pius V passed away in 1541—among those in attendance at the 1541 Papal Conclave included

Cardinal Reginald Pole, who served as Bishop of Salisbury and was a close associate of Queen Mary. The supposed

Papabili included

Alessandro Farnese—the last surviving cardinal created by Alexander VI but seen unfavorably because of his advanced age. Others were

Niccolò Ridolfi, nephew of Leo X. The ultimate victor was

Cardinal Girolamo Ghinucci, who took up the mantle of Pope as

Gelasius III. Compared to Pius V, Gelasius less favorable to the French than his predecessor—a fact hailed positively among the Papal camarilla. Other princes in Italy saw the need to maintain friendly—or at the very least, cordial—relations with France, lest they end up deprived of their lands like the Duke of Savoy. Lorenzo III, the Duke of Florence, though married (somewhat unhappily) to Joanna of Austria, the emperor’s illegitimate daughter, continued to maintain friendly relations with France—alongside the Duke of Ferrara and Modena. The Duke of Mantua (rewarded his title in 1530 by Charles V as part of his assistance during the War of the League of Valenciennes) remained wary of French power—while the Marquises of Montferrat and Saluzzo remained loyal French satraps in northern Italy.

Pope Gelasius III, c. 1543.

The French court of François remained debauched as ever—this did not change as France entered the 1540s.

“The king did as he pleased, and dallied where the Duchess of Plaisance wished him to dally,” one critic attacking the immortality of the king’s court wrote in 1541.

“Fontainebleau, Amboise—they are all domains of harlots and atheists; ladies of the most sophisticated blood paint themselves as whores, while even the holiest cardinals and servants of God can find pleasure in the French court—either with courtesans or pretty young men. King François is a whoremonger of the highest order—he stands for lewdness, immorality, and vice. He is no true Christian, or true Catholic—a vain Luciferian after only his pleasure.” Georges de Boullan, as Duke of Valentinois continued to be a close associate and friend of François—even after his sister had ceased to sleep with the king.

“Have you truly left the king’s bed, sister?” George reportedly japed to Anne when he discovered the news.

“Perhaps this old horse can finally have a break—and you shall finally be able to get off of your back!” Despite this, Boullan fortunes remained high into the 1540s—François continued to lavish gifts upon his favored ‘friend’—and she continued to wield influence. Though some circles hoped to foist one of François’ petit amours from one of Anne’s gardens into the seat of influence as his official mistress, François had little desire for it: the king, in his mid-forties and approaching his fifties still maintained a large sexual appetite, but the companionship which Anne de Boullan provided him could not be purchased—no little waif from her garden could compare to her on that front.

While the king reigned supreme, his eldest son, the Dauphin formally was right behind him. As the Dauphin entered his adulthood, he became a lightning rod for those opposed to the policies of the king. The Dauphin François was a loyal son—though he despaired of his father’s debaucheries and perhaps feared for his life. The Dauphin had a cordial relationship with Anne de Boullan—and a less cordial relationship with Queen Beatriz.

“The Dauphin had never cared for the queen—and the queen had not cared for him, either,” Sebastiano de Montecuccoli, secretary to the Dauphin wrote in a letter to his wife.

“Relations between them became more difficult following the birth of the queen’s son, Philippe—she saw a brighter future for her son outside of being Duc d’Orléans.” Though the Dauphin and Dauphine often resided at court, they also had their residences: King François had given the pair the Hôtel de Bourgogne as their Parisian residence. Dauphine Isabelle soon convinced her husband to raze the entire residence to build a new Renaissance townhouse where it once stood—the

Hôtel du Dauphin. They also possessed the Château of Blois and were given use of the Château des Ducs de Bretagne in Nantes. Compared to his father, the Dauphin François adored his wife, Isabelle.

“He loved her from the very first day he had set eyes upon her,” one courtier wrote in their memoirs regarding the court.

“… and she felt the same about him.” A keen romantic, the Dauphin often left his wife various poems and trinkets as part of their romantic games of chivalry.

“They were more in love than anyone could ever imagine at our court…” another courtier noted in their letters back home to their parents.

“If one could not find the Dauphin, they had only to seek out the Dauphine… for he was often in her chambers. They were seldom apart and were happiest in each other’s company…” Little surprise that the marriage was fruitful; in 1539, Isabelle would give birth to her first child—a son named

François in honor of his father and grandfather. This would be followed by a stillborn daughter in 1541, with a second son,

Louis born in 1542.

Dauphin François in armor; c. 1540.

Marriage was also paramount in Anne de Boullan’s mind and in Queen Beatriz's. Queen Beatriz harbored high hopes for her son, Philippe Emmanuel—who she called her

florzinha, or little flower. Philippe had become Duke of Orléans following the death of his oldest brother in 1538, but Beatriz sought great fortune for her son.

“Some saw great malice in the queen’s machinations…” François of Bourbon, the Duke of Estouteville would write in his memoirs.

“…for it was clear that Queen Beatriz desired for her son to have a crown just as well as his elder brother would have one. Many believed the queen would do away with the Dauphin—or do anything to see her son become King of France. But that is false, though she is no friend of mine; she abhorred France and wished her son to be sovereign elsewhere.” One of Beatriz’s first plans concerned her homeland.

“I have heard that the Infante Carlos is unwell…” Beatriz wrote in a letter to her brother in 1538.

“Your nephew Philippe Emmanuel grows stronger each year… and looks more and more like our dearly departed father. I desire nothing more than for my son to have a proper wife, and hope you might consider a marriage between him and the Infanta Beatriz…” Yet when young Carlos recovered, Beatriz soon set her sights upon Navarre—desiring that her son should wed Françoise Fébe, heiress to that small kingdom.

“Owing to the warm relations between our two lands,” Beatriz began in a letter addressed to Henri II and Marguerite of Angoulême.

“It is my greatest wish that you might consider the offer of my son’s hand for your daughter… they are close in age, and nothing would ensure Navarre’s protection more than to have a son of the House of Valois serve as its king.” Though Henri II was interested in the offer, Marguerite angrily rebuked it—complaining to her brother, who reminded Beatriz sternly that

he would decide his son’s future marriage.

While the queen was restrained, the mistress had freedom to negotiate the marriages of the king’s

bâtardes. In 1540, François formally legitimized his children with Anne de Boullan—granting them formal recognition and the surname of d’Angoulême. Élisabeth d’Angoulême, Anne’s eldest daughter was betrothed in 1540 to François of Bourbon, Count of Enghien and younger son of the Duke of Vendôme. Anne’s second daughter, Jacqueline d’Angoulême would be engaged to Gaspard II of Coligny—the Seigneur of Châtillion and son of late Marshal of Châtillion. Young Octave d’Angoulême, Anne’s lone son—would eventually inherit the bulk of her fortune and her ducal title.

“I shall find him a wife in due time,” Anne reportedly told the king with a sly smile.

“But he is yet a boy. Let him play with his blocks and soldiers—the marriage bed can come later.” A possible marriage was rumored between the king's illegitimate son and his niece: Princess Françoise of Navarre; this was soundly denied. Some believed that Marguerite had long desired for her daughter to marry François of Bourbon, son of the disgraced Constable of Bourbon—until his religious life had ruined such possibilities.