Chapter 20. Dawn of the Marian Age

1527-1532; England

“Flora extending the sensible odors

Of every flower the famous property

Regard the rose with ruby colors

With the pomegranate of pure progeny

Behold the fruit most like the deity

Of noble daughter in dignity.”

— William Newman, the Redolent Pryncesse.

Music Accompaniment: Queine of Ingland's Pavan & Gallyard

Catherine of Aragon, Queen Dowager & Regent of England, c. 1525.

The completion of negotiations for Queen Mary’s eventual marriage to Prince John of Denmark represented the last stages of Catherine’s regency. Mary, having inherited the English throne as a mere infant, was now rapidly growing into a young woman. Her mother’s regency would terminate upon her eighteenth birthday—December 31st, 1531—leaving only a few more years before Mary’s reign would begin. By 1528, Catherine of Aragon had served as Regent of England for over fifteen years—longer than her husband had ever reigned himself. Though Catherine’s government had suffered from her involvement in continental affairs, her focus in 1526 had returned to England. She desired not only to lay the groundwork for Mary to have a successful reign but hoped to ensure that she would have a successful marriage—and successful progeny, in due course.

Catherine had maintained the same Privy Council throughout her regency—having inherited her councilors from Henry VIII—some of them having even served the king’s late father, Henry VII. By the mid-1520s, many of these men were growing older and several even begged the queen for leave to retire. “The queen had been cautious in for the majority of her regency,” wrote one historian of the period. “The queen had been young, and the queen-regent needed guidance. When the alliance with the emperor proved fruitless, and the aged men of the council began to retire or die… Queen Catherine now had the means to shape the council in her image. The last years of her regency would be her most fruitful—she came into her own as regent and governor of the English realm and pursued the policies she thought most prudent.” One of the first to go was William Warham as Lord Chancellor in 1527—he was replaced with Bishop John Fisher, a noted opponent of the reform moment. Richard Foxe, as Lord Privy Seal, died in 1528—and was replaced by Sir Thomas More, while Henry Courtenay, the Marquess of Exeter succeeded Thomas Lovell as Chancellor of the Exchequer.

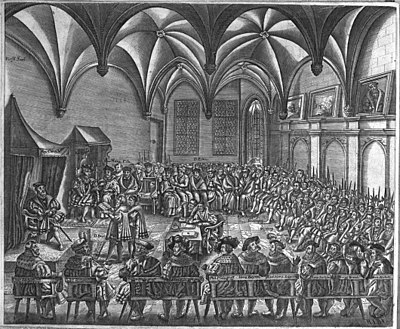

Under Fisher’s chancellorship, Catherine focused more on administrative and religious affairs. The growth of Luther’s reform movement in Germany had caused Catherine great unease—though she was an avowed Humanist and an admirer of Erasmus, she considered Luther someone else entirely. “A dangerous monk—with even more dangerous ideas,” Catherine wrote in a private letter to Margaret Pole. Luther’s ideas became known within England by the early 1520s and in 1526, an English translation of the New Testament was published by William Tyndale in Germany, where it was printed abroad and then smuggled into England—leading to a proliferation of Protestant ideas amongst the growing commercial classes. Both the queen regent and Bishop Fisher were gravely concerned by what they believed to be the spread of heretical ideas. Parliament was summoned in 1527—known as the Blessed Parliament by the supporters of the queen-regent, it gained an alternate name among supporters of the reformation: the Parliament of Flames. The session of the 1527 Parliament primarily dealt with passing the Heresy Act of 1527 which served to modernize the Heresy Acts of 1382, 1401, and 1414 by compiling them into a single act—as well as allowing punishments and sentences to be meted out to Lutherans, including burnings. The act also provided for the establishment of what would become known as the Central Heresy Court in London, which would become responsible for trying all cases of heresy within England and Wales and passing sentences upon those found guilty. The court would be headed by a tribunal of bishops. The court was empowered to do its job through court commissioners, who would be allowed into all English and Welsh parishes; their duties would be to collect information and interrogate suspected heretics—in effect building up a bureaucracy whose job would be to hunt down heretics. This represented a union of secular and ecclesiastical powers—working together.

Bishop John Fisher; as Lord Chancellor, he prioritized the fight against heresy.

Other acts sought to reinvigorate the state of the Catholic Church in England. The Religious Houses Reorganization Act allowed for the dissolution of monasteries that were indebted and small (having less than twelve members) to fund educational and social foundations—Frideswide College at Oxford was founded through the Reorganization Act, as well as the St. Magdalene Hospital in London—one of England’s first hospitals dedicated to the treatment of venereal diseases. Catherine also sought to invite other religious orders into England, in hopes that monastic life—which had declined, might be regenerated. A group of Hieronymite nuns from the Order of Saint Jerome from Catherine’s native Spain were invited to create a priory near the village of Speldhurst in Kent, while the Servite Order was given land in Greatham in Durham. The Organization Act also laid out stipulations for new religious houses that might be founded by requiring that they have a mission within the community where they would be based: by dispensing charity or through good works, such as providing education or medical care. By requiring new religious endowments, even of contemplative orders to engage in practical and worthy causes, Catherine hoped that such religious houses might be integrated into the communities where they would settle—not only attracting donations that would allow them to become self-sufficient but also proving their worth and reducing the idleness of the monks and nuns by aiding the communities where they would reside. Catherine also sought Papal approval to change the crown’s rights to clerical revenues—hereto limited to extraordinary levies and subsidies. Pius IV, much like his successor Pius V made certain concessions to England which resulted in the Convocation Act. The Convocation Act would allow the crown to raise new revenue from new clerical sources by allowing taxation upon clerical tithes as well as clerical rents and income—with the caveat that all such taxes would be grants—and that they would need to be need approved by the Convocation of Canterbury or the Convocation of York by the clergy themselves.

Administrative reforms concerned Wales. Buckingham’s Rebellion in 1520 had spooked Queen Catherine as well as her council—and it was in 1526 that George Talbot and the Council of Wales recommended a program for Wales that would bind it closer to England. The resulting program would become the Laws in Wales Act which proclaimed that Wales was incorporated and united with the crown of England. This ended the Principality of Wales’s unique status within England; the English language and English law were imposed for the first time across the whole of Wales—with Wales being granted representation in Parliament. The Marcher Lordships were abolished as political units, with counties being created in Welsh territory—Monmouthshire, Brenockshire, Radnorshire, Montgomeryshire, and Denbighshire. Other lordships were annexed into already existing counties. Ireland had its issues—feuding had flared up between the Earls of Butler and Ormond in the 1520s, and Catherine attempted to bring peace between the feuding factions by appointing Henry Bouchier, the Earl of Essex as Lord Lieutenant of Ireland.

Meanwhile, Queen Mary continued to grow—and her role as queen became even more visible as she entered her later teenage years, even as she remained under the effective tutelage of her mother. Her education entered its final stages—with lessons of government transformed from erudite practices under Thomas More and her other tutors into more practical lessons. By the age of fifteen, Mary’s signature could be found on government papers and documents as a countersignature alongside her mother’s signature as regent. The young queen also began to attend meetings of the council—first incognito, and then in person. “Her Grace, despite her youth, took to the business of government easily,” one councilor wrote anonymously. “She is less indolent than the late king and prefers to manage things then and there. When things are brought before her, she reads each thing carefully—she does not sign blindly and asks the correct questions.” Nor was the young queen afraid to speak her mind—she was not afraid of offering her own opinion within these council meetings, even if she did not yet possess the necessary authority to sway anyone. All began to look less towards the mother—and more towards the daughter, who would quite soon be their sovereign in all aspects.

In 1529, Catherine and Mary departed on royal progress—the first Tudor progress since 1498, when Prince Arthur had toured Coventry. The tour lasted throughout the summer—Mary and her mother were hosted at Rockingham Castle in Northamptonshire. One courtier wrote, “The queen hunted daily with her ladies, stalking deer throughout the woods of Rockingham.” From Rockingham, the court visited Coventry, as well as Coughton Court in Warwickshire, where Sir George Throckmorton hosted the queen and her mother. “Sir Throckmorton spared no expense in the young queen’s visit,” Charles Blount wrote in his youthful journal. “The welcoming feast was held in the great halls—bedecked with the royal standard; there were piles and piles of food, from which we all ate heartily—capons with lemon, roasted beef with Lombard mustard; sturgeon and lamprey pies. Dessert was just as sumptuous—marchpane, doucet, and tarts of sundry flavors…” The royal progress ended as the summer of 1529 died down—with Catherine and Mary hosted at Dorney Court before the progress ended at Eltham Palace.

Landscape with Roman Ruins, 16th Century.

As 1530 dawned, plans were put into motion to bring Mary’s future marriage to Prince John closer to fruition—with arrangements now set in motion for Prince John to come over to England to complete his education. While the marriage had lost its prime proponent following the death of Empress Mary in 1529, Charles V remained determined to honor his late wife’s wishes by finalizing the match. Prince John had a final interview with his uncle at Ghent, where the emperor offered his blessings as well as advice. “Always remember that you are a prince of our royal house—I send you to England as your aunt desired so that you will be a worthy husband to our cousin, Queen Mary—and so that you may be a king to aid her in the burdens of government.” Prince John soon left Ghent with a retinue that would accompany him to England—Johan von Weze, an imperial diplomat and his father’s former secretary would serve as his secretary, while a few young men were to accompany Prince John as companions—this included René of Nassau-Breda[1], Antoine de Perrenot de Granvelle, and Ascanio Arianiti—son of an Italian nobleman who had become attached to the Imperial cause—Prince Arianitto Cominato Arianiti. John and his suite soon departed for Antwerp, where they were met by Adolf of Burgundy, the Admiral of Burgundy. John’s flagship would be a warship, the Duke of Burgundy. Prince John then soon departed the Low Countries—to head towards England, his future home and kingdom.

The English court was expecting the arrival of Prince John and had decamped to Dover, where they took up residence in Dover Castle. “The queen was most agitated in those days before the prince’s arrival,” One of her ladies, Anne Parr wrote in her private arrival. “She had a most foul temper—made worse by a malaise which she was suffering from. On our first day at Dover, she complained of pain in her head and neck, as well as chills, and was forced to take to her bed. Within a few hours, she was delirious and burning hot. It was not the pox or any dreaded plague—it was the sweat.” Queen Mary, then sixteen was laid down with the Sweating Sickness—an English sickness known for its virulence and the fact that it carried off people quickly. An outbreak had occurred in 1526, but now it seemed that the disease had returned—striking at the heart of the court. The young queen, hale and hearty, was now struck down with a serious illness—the first of her reign. “I pray for her deliverance,” Catherine of Aragon wrote in a hurried letter to her foremost friend and confidante, Maria de Salinas. “I have been barred from her chambers on account of how quickly the sickness spreads… my confessor encourages me to put my faith in God, while the doctors do the best they can.” The queen’s malady put the queen-regent into despair—with one courtier writing “She could not eat or drink, nor did she sleep—she worried only about the queen; some believe that the sickness conjured up terrible memories of the queen’s first marriage—when she and Prince Arthur were both laid down with a terrible malady…” Though Mary’s care was at first managed by the doctors and apothecaries of the royal household, Catherine soon turned to a foreign doctor who offered his advice: João Rodrigues, a Portuguese surgeon practicing in London who was rumored in some circles to be a Marrano. With the queen regent’s consent, Rodrigues took over the young queen’s care, to the chagrin of the royal physicians. “He has forbidden us from bleeding her—and has rudely proclaimed that our physics and tonics are useless,” One royal apothecary wrote haughtily within his journals. “He has instead instructed the queen’s servants to keep the fire burning within her chambers at all hours and give her a remedy of his concoction. That the Queen of England should be served by such a man, we ought to say our prayers.” Mary lingered before life and death—her last rights were administered by her almoner, and she even drafted her last will—leaving precious jewels to her favorited ladies, while asking the council to bestow £10,000 upon her mother in reward for her services as regent. One final item concerned her successor: “As I am the sole heir of my father and lone Tudor in England,” Mary wrote wearily upon the parchment, her normally precise handwriting a wearied scratch. “There remains only one Tudor after me—and she shall be my successor and your queen—my aunt, Margaret. The crown shall pass to her—and in due course, my cousin the King of Scotland.”

The court waited with bated breath—awaiting the proclamation that their queen was gone. Mary lingered in a perilous condition for several days, but the sweat began to cease, and her fatigue began to fade. The queen had nearly died—but she had survived, to the jubilation of the court and as well as her mother. “She lives,” Catherine wrote tearfully to Maria de Salinas. “She lives and will continue to live.” João Rodrigues was rewarded for his role in the queen’s survival with a pension of £100. It was in this happiest of situations that news was brought to Dover of Prince John’s arrival—his ship had endured terrible weather while crossing the channel, and the ship had been blown off course. Instead of landing at Dover, John and his suite had instead landed at Margate and were expected at Dover by nightfall. In a hurry, the servants did their best to sweeten the castle and prepare for the arrival of their sovereign’s future husband—and their future king. The first meeting between Queen Mary and Prince John took place within the queen’s chamber because she was still recovering from her illness. “The queen received the prince within her privy chapter—with the queen-regent present as a chaperone,” one anonymous courtier wrote in a letter to their family about the meeting. “Despite the queen having just recently recovered, she looked every inch the sovereign—she wore a French hood trimmed with pearls, while her gown was made of silver cloth—with the bodice decorated with a brocade of flowers. The queen’s jewelry was simple—a pearl necklace and pearl earrings—with a girdle belt decorated with Tudor Roses that extended from around her waist down to the middle of her gown. Prince John was polite and quiet as he bowed before Mary to offer his obeisance. At twelve, he looked more like a younger brother paying honor to his older sister, rather than a bridegroom… but the queen accepted his speech with a polite smile before she bid him to rise…”

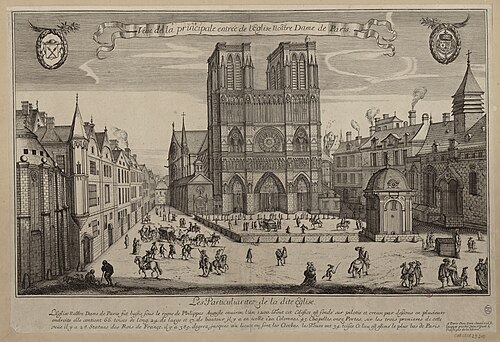

Portrait of a Young Woman, believed to be Queen Mary, c. 1530.

Queen Mary was less impressed in private, lamenting to Anne Parr that: “They have sent me a boy to be my husband.” Still, many were impressed with the young prince—and Catherine of Aragon reminded her daughter that there would still be four years before the pair would marry: plenty of time for Prince John to grow into the man that he was meant to be. It was decided that given John’s relative youth and need to complete his education he would reside away from court—and was given Oldhall House[2] over to his use. Catherine of Aragon granted the wardship of Prince John to the Duke of Norfolk, who arranged for William Latimer, a priest and scholar in ancient Greek to tutor John in languages—primarily Greek, English, and Italian, while Stephen Gardinier, an archdeacon, was appointed to tutor John in English history and government. Prince John took to his studies—though Norfolk lamented in a letter to Catherine of Aragon that, “Though the prince takes to his lessons, I fear he is not as dutiful as we might have hoped—and Master Latimer has been forced to apply the birch more than I would have liked.” It was reported that John was often homesick; matters were made worse when news arrived in late 1531 that the prince’s father had been captured in Norway while trying to reclaim his throne. Promised safe conduct by King Frederick, Christian II soon found himself betrayed—and imprisoned at Sønderborg Castle in Denmark.

On December 31st, 1531, Queen Mary celebrated her eighteenth birthday. Her brush with death the previous year had been put behind her, and many remarked that she seemed as healthy as she had been previously. On the morning of her eighteenth birthday, a ceremony was held to commemorate the queen having attained the majority. In the great hall of Richmond Palace, a great dais had been erected upon which two thrones sat—one for the queen-regent, and one for the queen. Catherine of Aragon was dressed in a gown of black velvet, along with her robes of state and the crown she had worn to her coronation—while Mary was in a gown of white taffeta, with her hair loose. Before the assembled court, the ladies of Catherine’s chamber assisted the queen-regent in removing the symbols of her authority—her robes of state and her crown. Dressed now in her widow’s colors, her ladies replaced her crown with a widow’s cap of black velvet—along with a veil of translucent black silk. “Milords—it has been some eighteen years since I have carried the burdens of state; and eighteen years since the birth of my daughter, your queen.” Catherine began her farewell speech. “You see before you now a grown woman—I have raised her to the best of my ability, not just to be a good wife and good Catholic—but a great queen. Since her birth, she has belonged to this realm of England, and now she has attained her majority. She shall be your sovereign in name as well as deed. I am but an old woman now, and a widow of my husband—your dearly departed king. The burdens of government and this realm must be taken up by his daughter; you require a sovereign who possesses youth and vitalty, and the blood of this nation. Though it has been my greatest honor to serve you, I beg your leave to retire—whatever years God sees fit to grant me beyond this, I wish to spend in peace.” Many tears were shed following the queen regent’s speech—with cries of “God Save Queen Catherine!” ringing out throughout the hall. Though her popularity had suffered due to her close association with the emperor, her popularity had rebounded in the final years of her regency; and though the people were happy to see Queen Mary take her rightful place, they knew that good government had been provided in her youth—and the years of Catherine’s regency had been relatively prosperous.

With Catherine’s symbols of authority removed, Queen Mary’s were soon placed upon her—with the roles being reversed. Catherine of Aragon, formally Regent of England, and the authority within the realm was now merely the Queen Dowager—all authority now rested in the hands of Queen Mary as Queen of England—England’s first. Mary soon gave her speech: “I know that I have come to this throne young—younger than most, and now I attain my majority at eighteen when most princes are content to sit at their father’s feet. This is not a luxury that I possess; and though the title of king is a glorious one that people might yearn for, I promise you, good people of England, that I shall strive to ensure that the title of queen is as glorious as well. As your sovereign I promise to serve you honestly and justly and provide what this kingdom and its people should desire for as long as I am called to reign over it—just as Mary was the Mother of God, so I shall always be the Mother of England.”

[1]As Prince Philibert of Châlon is still alive, René bare his original name here.

[2]OTL Hunsdon House

1527-1532; England

“Flora extending the sensible odors

Of every flower the famous property

Regard the rose with ruby colors

With the pomegranate of pure progeny

Behold the fruit most like the deity

Of noble daughter in dignity.”

— William Newman, the Redolent Pryncesse.

Music Accompaniment: Queine of Ingland's Pavan & Gallyard

Catherine of Aragon, Queen Dowager & Regent of England, c. 1525.

The completion of negotiations for Queen Mary’s eventual marriage to Prince John of Denmark represented the last stages of Catherine’s regency. Mary, having inherited the English throne as a mere infant, was now rapidly growing into a young woman. Her mother’s regency would terminate upon her eighteenth birthday—December 31st, 1531—leaving only a few more years before Mary’s reign would begin. By 1528, Catherine of Aragon had served as Regent of England for over fifteen years—longer than her husband had ever reigned himself. Though Catherine’s government had suffered from her involvement in continental affairs, her focus in 1526 had returned to England. She desired not only to lay the groundwork for Mary to have a successful reign but hoped to ensure that she would have a successful marriage—and successful progeny, in due course.

Catherine had maintained the same Privy Council throughout her regency—having inherited her councilors from Henry VIII—some of them having even served the king’s late father, Henry VII. By the mid-1520s, many of these men were growing older and several even begged the queen for leave to retire. “The queen had been cautious in for the majority of her regency,” wrote one historian of the period. “The queen had been young, and the queen-regent needed guidance. When the alliance with the emperor proved fruitless, and the aged men of the council began to retire or die… Queen Catherine now had the means to shape the council in her image. The last years of her regency would be her most fruitful—she came into her own as regent and governor of the English realm and pursued the policies she thought most prudent.” One of the first to go was William Warham as Lord Chancellor in 1527—he was replaced with Bishop John Fisher, a noted opponent of the reform moment. Richard Foxe, as Lord Privy Seal, died in 1528—and was replaced by Sir Thomas More, while Henry Courtenay, the Marquess of Exeter succeeded Thomas Lovell as Chancellor of the Exchequer.

Under Fisher’s chancellorship, Catherine focused more on administrative and religious affairs. The growth of Luther’s reform movement in Germany had caused Catherine great unease—though she was an avowed Humanist and an admirer of Erasmus, she considered Luther someone else entirely. “A dangerous monk—with even more dangerous ideas,” Catherine wrote in a private letter to Margaret Pole. Luther’s ideas became known within England by the early 1520s and in 1526, an English translation of the New Testament was published by William Tyndale in Germany, where it was printed abroad and then smuggled into England—leading to a proliferation of Protestant ideas amongst the growing commercial classes. Both the queen regent and Bishop Fisher were gravely concerned by what they believed to be the spread of heretical ideas. Parliament was summoned in 1527—known as the Blessed Parliament by the supporters of the queen-regent, it gained an alternate name among supporters of the reformation: the Parliament of Flames. The session of the 1527 Parliament primarily dealt with passing the Heresy Act of 1527 which served to modernize the Heresy Acts of 1382, 1401, and 1414 by compiling them into a single act—as well as allowing punishments and sentences to be meted out to Lutherans, including burnings. The act also provided for the establishment of what would become known as the Central Heresy Court in London, which would become responsible for trying all cases of heresy within England and Wales and passing sentences upon those found guilty. The court would be headed by a tribunal of bishops. The court was empowered to do its job through court commissioners, who would be allowed into all English and Welsh parishes; their duties would be to collect information and interrogate suspected heretics—in effect building up a bureaucracy whose job would be to hunt down heretics. This represented a union of secular and ecclesiastical powers—working together.

Bishop John Fisher; as Lord Chancellor, he prioritized the fight against heresy.

Other acts sought to reinvigorate the state of the Catholic Church in England. The Religious Houses Reorganization Act allowed for the dissolution of monasteries that were indebted and small (having less than twelve members) to fund educational and social foundations—Frideswide College at Oxford was founded through the Reorganization Act, as well as the St. Magdalene Hospital in London—one of England’s first hospitals dedicated to the treatment of venereal diseases. Catherine also sought to invite other religious orders into England, in hopes that monastic life—which had declined, might be regenerated. A group of Hieronymite nuns from the Order of Saint Jerome from Catherine’s native Spain were invited to create a priory near the village of Speldhurst in Kent, while the Servite Order was given land in Greatham in Durham. The Organization Act also laid out stipulations for new religious houses that might be founded by requiring that they have a mission within the community where they would be based: by dispensing charity or through good works, such as providing education or medical care. By requiring new religious endowments, even of contemplative orders to engage in practical and worthy causes, Catherine hoped that such religious houses might be integrated into the communities where they would settle—not only attracting donations that would allow them to become self-sufficient but also proving their worth and reducing the idleness of the monks and nuns by aiding the communities where they would reside. Catherine also sought Papal approval to change the crown’s rights to clerical revenues—hereto limited to extraordinary levies and subsidies. Pius IV, much like his successor Pius V made certain concessions to England which resulted in the Convocation Act. The Convocation Act would allow the crown to raise new revenue from new clerical sources by allowing taxation upon clerical tithes as well as clerical rents and income—with the caveat that all such taxes would be grants—and that they would need to be need approved by the Convocation of Canterbury or the Convocation of York by the clergy themselves.

Administrative reforms concerned Wales. Buckingham’s Rebellion in 1520 had spooked Queen Catherine as well as her council—and it was in 1526 that George Talbot and the Council of Wales recommended a program for Wales that would bind it closer to England. The resulting program would become the Laws in Wales Act which proclaimed that Wales was incorporated and united with the crown of England. This ended the Principality of Wales’s unique status within England; the English language and English law were imposed for the first time across the whole of Wales—with Wales being granted representation in Parliament. The Marcher Lordships were abolished as political units, with counties being created in Welsh territory—Monmouthshire, Brenockshire, Radnorshire, Montgomeryshire, and Denbighshire. Other lordships were annexed into already existing counties. Ireland had its issues—feuding had flared up between the Earls of Butler and Ormond in the 1520s, and Catherine attempted to bring peace between the feuding factions by appointing Henry Bouchier, the Earl of Essex as Lord Lieutenant of Ireland.

Meanwhile, Queen Mary continued to grow—and her role as queen became even more visible as she entered her later teenage years, even as she remained under the effective tutelage of her mother. Her education entered its final stages—with lessons of government transformed from erudite practices under Thomas More and her other tutors into more practical lessons. By the age of fifteen, Mary’s signature could be found on government papers and documents as a countersignature alongside her mother’s signature as regent. The young queen also began to attend meetings of the council—first incognito, and then in person. “Her Grace, despite her youth, took to the business of government easily,” one councilor wrote anonymously. “She is less indolent than the late king and prefers to manage things then and there. When things are brought before her, she reads each thing carefully—she does not sign blindly and asks the correct questions.” Nor was the young queen afraid to speak her mind—she was not afraid of offering her own opinion within these council meetings, even if she did not yet possess the necessary authority to sway anyone. All began to look less towards the mother—and more towards the daughter, who would quite soon be their sovereign in all aspects.

In 1529, Catherine and Mary departed on royal progress—the first Tudor progress since 1498, when Prince Arthur had toured Coventry. The tour lasted throughout the summer—Mary and her mother were hosted at Rockingham Castle in Northamptonshire. One courtier wrote, “The queen hunted daily with her ladies, stalking deer throughout the woods of Rockingham.” From Rockingham, the court visited Coventry, as well as Coughton Court in Warwickshire, where Sir George Throckmorton hosted the queen and her mother. “Sir Throckmorton spared no expense in the young queen’s visit,” Charles Blount wrote in his youthful journal. “The welcoming feast was held in the great halls—bedecked with the royal standard; there were piles and piles of food, from which we all ate heartily—capons with lemon, roasted beef with Lombard mustard; sturgeon and lamprey pies. Dessert was just as sumptuous—marchpane, doucet, and tarts of sundry flavors…” The royal progress ended as the summer of 1529 died down—with Catherine and Mary hosted at Dorney Court before the progress ended at Eltham Palace.

Landscape with Roman Ruins, 16th Century.

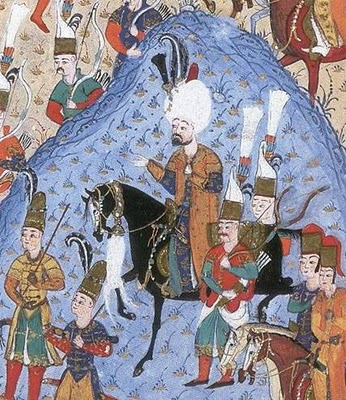

As 1530 dawned, plans were put into motion to bring Mary’s future marriage to Prince John closer to fruition—with arrangements now set in motion for Prince John to come over to England to complete his education. While the marriage had lost its prime proponent following the death of Empress Mary in 1529, Charles V remained determined to honor his late wife’s wishes by finalizing the match. Prince John had a final interview with his uncle at Ghent, where the emperor offered his blessings as well as advice. “Always remember that you are a prince of our royal house—I send you to England as your aunt desired so that you will be a worthy husband to our cousin, Queen Mary—and so that you may be a king to aid her in the burdens of government.” Prince John soon left Ghent with a retinue that would accompany him to England—Johan von Weze, an imperial diplomat and his father’s former secretary would serve as his secretary, while a few young men were to accompany Prince John as companions—this included René of Nassau-Breda[1], Antoine de Perrenot de Granvelle, and Ascanio Arianiti—son of an Italian nobleman who had become attached to the Imperial cause—Prince Arianitto Cominato Arianiti. John and his suite soon departed for Antwerp, where they were met by Adolf of Burgundy, the Admiral of Burgundy. John’s flagship would be a warship, the Duke of Burgundy. Prince John then soon departed the Low Countries—to head towards England, his future home and kingdom.

The English court was expecting the arrival of Prince John and had decamped to Dover, where they took up residence in Dover Castle. “The queen was most agitated in those days before the prince’s arrival,” One of her ladies, Anne Parr wrote in her private arrival. “She had a most foul temper—made worse by a malaise which she was suffering from. On our first day at Dover, she complained of pain in her head and neck, as well as chills, and was forced to take to her bed. Within a few hours, she was delirious and burning hot. It was not the pox or any dreaded plague—it was the sweat.” Queen Mary, then sixteen was laid down with the Sweating Sickness—an English sickness known for its virulence and the fact that it carried off people quickly. An outbreak had occurred in 1526, but now it seemed that the disease had returned—striking at the heart of the court. The young queen, hale and hearty, was now struck down with a serious illness—the first of her reign. “I pray for her deliverance,” Catherine of Aragon wrote in a hurried letter to her foremost friend and confidante, Maria de Salinas. “I have been barred from her chambers on account of how quickly the sickness spreads… my confessor encourages me to put my faith in God, while the doctors do the best they can.” The queen’s malady put the queen-regent into despair—with one courtier writing “She could not eat or drink, nor did she sleep—she worried only about the queen; some believe that the sickness conjured up terrible memories of the queen’s first marriage—when she and Prince Arthur were both laid down with a terrible malady…” Though Mary’s care was at first managed by the doctors and apothecaries of the royal household, Catherine soon turned to a foreign doctor who offered his advice: João Rodrigues, a Portuguese surgeon practicing in London who was rumored in some circles to be a Marrano. With the queen regent’s consent, Rodrigues took over the young queen’s care, to the chagrin of the royal physicians. “He has forbidden us from bleeding her—and has rudely proclaimed that our physics and tonics are useless,” One royal apothecary wrote haughtily within his journals. “He has instead instructed the queen’s servants to keep the fire burning within her chambers at all hours and give her a remedy of his concoction. That the Queen of England should be served by such a man, we ought to say our prayers.” Mary lingered before life and death—her last rights were administered by her almoner, and she even drafted her last will—leaving precious jewels to her favorited ladies, while asking the council to bestow £10,000 upon her mother in reward for her services as regent. One final item concerned her successor: “As I am the sole heir of my father and lone Tudor in England,” Mary wrote wearily upon the parchment, her normally precise handwriting a wearied scratch. “There remains only one Tudor after me—and she shall be my successor and your queen—my aunt, Margaret. The crown shall pass to her—and in due course, my cousin the King of Scotland.”

The court waited with bated breath—awaiting the proclamation that their queen was gone. Mary lingered in a perilous condition for several days, but the sweat began to cease, and her fatigue began to fade. The queen had nearly died—but she had survived, to the jubilation of the court and as well as her mother. “She lives,” Catherine wrote tearfully to Maria de Salinas. “She lives and will continue to live.” João Rodrigues was rewarded for his role in the queen’s survival with a pension of £100. It was in this happiest of situations that news was brought to Dover of Prince John’s arrival—his ship had endured terrible weather while crossing the channel, and the ship had been blown off course. Instead of landing at Dover, John and his suite had instead landed at Margate and were expected at Dover by nightfall. In a hurry, the servants did their best to sweeten the castle and prepare for the arrival of their sovereign’s future husband—and their future king. The first meeting between Queen Mary and Prince John took place within the queen’s chamber because she was still recovering from her illness. “The queen received the prince within her privy chapter—with the queen-regent present as a chaperone,” one anonymous courtier wrote in a letter to their family about the meeting. “Despite the queen having just recently recovered, she looked every inch the sovereign—she wore a French hood trimmed with pearls, while her gown was made of silver cloth—with the bodice decorated with a brocade of flowers. The queen’s jewelry was simple—a pearl necklace and pearl earrings—with a girdle belt decorated with Tudor Roses that extended from around her waist down to the middle of her gown. Prince John was polite and quiet as he bowed before Mary to offer his obeisance. At twelve, he looked more like a younger brother paying honor to his older sister, rather than a bridegroom… but the queen accepted his speech with a polite smile before she bid him to rise…”

Portrait of a Young Woman, believed to be Queen Mary, c. 1530.

Queen Mary was less impressed in private, lamenting to Anne Parr that: “They have sent me a boy to be my husband.” Still, many were impressed with the young prince—and Catherine of Aragon reminded her daughter that there would still be four years before the pair would marry: plenty of time for Prince John to grow into the man that he was meant to be. It was decided that given John’s relative youth and need to complete his education he would reside away from court—and was given Oldhall House[2] over to his use. Catherine of Aragon granted the wardship of Prince John to the Duke of Norfolk, who arranged for William Latimer, a priest and scholar in ancient Greek to tutor John in languages—primarily Greek, English, and Italian, while Stephen Gardinier, an archdeacon, was appointed to tutor John in English history and government. Prince John took to his studies—though Norfolk lamented in a letter to Catherine of Aragon that, “Though the prince takes to his lessons, I fear he is not as dutiful as we might have hoped—and Master Latimer has been forced to apply the birch more than I would have liked.” It was reported that John was often homesick; matters were made worse when news arrived in late 1531 that the prince’s father had been captured in Norway while trying to reclaim his throne. Promised safe conduct by King Frederick, Christian II soon found himself betrayed—and imprisoned at Sønderborg Castle in Denmark.

On December 31st, 1531, Queen Mary celebrated her eighteenth birthday. Her brush with death the previous year had been put behind her, and many remarked that she seemed as healthy as she had been previously. On the morning of her eighteenth birthday, a ceremony was held to commemorate the queen having attained the majority. In the great hall of Richmond Palace, a great dais had been erected upon which two thrones sat—one for the queen-regent, and one for the queen. Catherine of Aragon was dressed in a gown of black velvet, along with her robes of state and the crown she had worn to her coronation—while Mary was in a gown of white taffeta, with her hair loose. Before the assembled court, the ladies of Catherine’s chamber assisted the queen-regent in removing the symbols of her authority—her robes of state and her crown. Dressed now in her widow’s colors, her ladies replaced her crown with a widow’s cap of black velvet—along with a veil of translucent black silk. “Milords—it has been some eighteen years since I have carried the burdens of state; and eighteen years since the birth of my daughter, your queen.” Catherine began her farewell speech. “You see before you now a grown woman—I have raised her to the best of my ability, not just to be a good wife and good Catholic—but a great queen. Since her birth, she has belonged to this realm of England, and now she has attained her majority. She shall be your sovereign in name as well as deed. I am but an old woman now, and a widow of my husband—your dearly departed king. The burdens of government and this realm must be taken up by his daughter; you require a sovereign who possesses youth and vitalty, and the blood of this nation. Though it has been my greatest honor to serve you, I beg your leave to retire—whatever years God sees fit to grant me beyond this, I wish to spend in peace.” Many tears were shed following the queen regent’s speech—with cries of “God Save Queen Catherine!” ringing out throughout the hall. Though her popularity had suffered due to her close association with the emperor, her popularity had rebounded in the final years of her regency; and though the people were happy to see Queen Mary take her rightful place, they knew that good government had been provided in her youth—and the years of Catherine’s regency had been relatively prosperous.

With Catherine’s symbols of authority removed, Queen Mary’s were soon placed upon her—with the roles being reversed. Catherine of Aragon, formally Regent of England, and the authority within the realm was now merely the Queen Dowager—all authority now rested in the hands of Queen Mary as Queen of England—England’s first. Mary soon gave her speech: “I know that I have come to this throne young—younger than most, and now I attain my majority at eighteen when most princes are content to sit at their father’s feet. This is not a luxury that I possess; and though the title of king is a glorious one that people might yearn for, I promise you, good people of England, that I shall strive to ensure that the title of queen is as glorious as well. As your sovereign I promise to serve you honestly and justly and provide what this kingdom and its people should desire for as long as I am called to reign over it—just as Mary was the Mother of God, so I shall always be the Mother of England.”

[1]As Prince Philibert of Châlon is still alive, René bare his original name here.

[2]OTL Hunsdon House

Last edited: