Chapter 24. Discord Along the Danube

1533-1535; Germany, Hungary & the Ottoman Empire.

“I am wholly resolved to help my brother—both because his need is so great and because the perils which threaten him place the whole of the Christendom at risk. I cannot and must not abandon him, not because of the position I occupy, or due to fraternal love—I must go to him because he is a good brother to me.”

— Ferdinand, Prince of Asturias; written to his wife, Isabella before his departure to Germany.

Music Accompaniment: Kirim'dan Gelirim

The Quaternion Eagle, Jost de Negler; c. 1510.

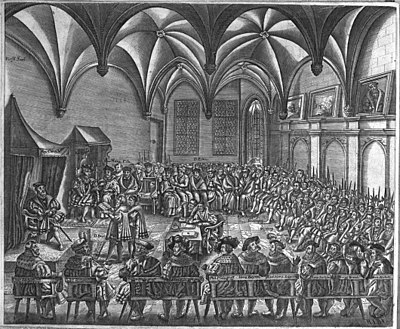

The Diet of Trier which closed in 1532 had ended with the summoning of a general council under the authority of the Holy Roman Empire. Termed a synod by Charles V, the

Synod of Trier was set to open in April of 1533. While the action was widely applauded by the squabbling factions within the empire—the news of the synod provoked a strong reaction when it reached Rome.

“Word has reached His Holiness of the planned council which you plan to host in Germany,” Cardinal Alessandro Piccolomini, cardinal-nephew to Pope Pius V wrote in a letter to the emperor.

“Authority for such matters rests in the hands of the Pope—and the Pope alone; the bull Execrabalis declares that the Pope as Vicar of Christ is the final authority within our church.” The letter was worded strongly—but without teeth. Though Pius V opposed the idea of a council in Germany without his participation, he was not prepared to make an enemy out of the emperor by acting out of rashness. Better to wait and see—while urging those who sought a council to pay heed to the Council of Verona, which remained primarily attended by French and Italian prelates. The Council of Verona would be closed in the spring of 1533—and postponed indefinitely, without having accomplished a single thing. Europe’s Catholic monarchs—outside of King François, who fumed at Charles's rejection of

his council—watched the events unfolding in Germany with great interest.

Meanwhile, the Ottoman army in Hungary, under the command of Sultan Suleiman himself spent the winter of 1532 into 1533 at

Szentendre. To ensure there were no issues, King John had the population of the town expelled—even the local church was requisitioned, and its priests expelled—with Szentendre Church converted into a mosque during the duration of the Turkish stay. The army, which numbered some 100,000 men, required many supplies—with food being the most important. While the centralized structure of the Ottoman Empire meant that a great portion of the needed supplies could be procured within the empire and transported to Hungary, not everything could be provided on time throughout the winter—which meant that the burden then fell upon Hungary.

“We have received another receipt from the Turks seeking supplies for the army garrisoned at Szetendre—our third this month,” István Werboczy wrote in a letter to John Zápolya.

“They require flour and salt most especially—and are prepared to pay us a further inducement if we assist in providing them these provisions. The Grand Vizier has also written seeking our assistance in gathering supplies for the coming campaign season… including some 50,000 sheep to be slaughtered for meat; oxen and horses to replace those that have perished; and fodder and grains to feed the animals.” While the need for the Turkish army allowed the Hungarian crown to profit, the burden fell most heavily upon the Hungarian peasantry, with the crown ordering forced requisitions of needed supplies.

The Synod of Trier opened in April of 1533 in the presence of Charles V. Empress Renée also attended—heavily pregnant—she would give birth to her first child, a daughter named

Anne in honor of her mother at Trier in June of 1533. The Catholic Party was represented by the Electors of Cologne, Mainz, and Trier as well as numerous Prince-Bishops and Prince-Archbishops. The Protestant Party were represented by their primary theologians—Martin Luther, and Philipp Melanchthon who represented the Lutheran school, while Martin Bucer and Wolfgang Capito attended as representatives of the Swabian Confession, prevalent in Alsace and portions of southern Germany. Mary of Austria sent representatives from Bohemia—this included not only Catholic theologians, such as Jan Dubravius but supporters of the Protestant movement and Ultraquists as well. Major Protestant princes also attended—with John Frederick, the Elector of Saxony, and Philip of Hesse also in attendance. Both groups were given equal time at the start of the synod to outline their beliefs and ideas—yet a tense atmosphere hung over the proceedings. Several Catholic prelates dramatically marched out of the Synod when Martin Luther in his opening speech attacked the abuses and corruption of the Papacy.

“The Pope is and remains the anti-Christ,” Luther thundered from his pulpit.

“He and his predecessors are liars—their domains were gained through both fraud and deception. Now, today, they continue to deceive, lying to all the Christendom; the Pope is above no one, from the greatest king to the meanest serf; Anyone armed with scripture can find salvation. there is no role for him here in Germany—it is us alone who can and should decide the future.” Protestant attendees proved just as disruptive; they heckled and jeered at the Prince-Bishop of Eichstätt when he attempted to give an impassioned defense of the Pope’s authority over the Catholic Church.

“It was at Trier that Charles V realized that the Protestant faith was no mere passing fancy or minor heresy,” Francesco Guicciardini, a historian of the period wrote in one of his seminal works,

Diario di Viaggio in Germania. “Grave divides separated the Catholic and Protestant faiths—it was not just theological disputes, but the disputes of their worldviews, too. How could the Catholics compromise with those who saw the head of their church as the anti-Christ? How could Protestants compromise with those who saw them as mischief-making heretics?”

Woodcut of the Synod of Trier.

The Synod’s opening weeks were spent in discussion on theological issues, such as sacraments, clerical marriage, and communion for the laity. Very little progress was made, and most discussions devolved into fierce arguments—with neither side prepared to give ground in their beliefs. It was only in discussions regarding communion that some common ground was found, with Catholic prelates conceding that there was no real doctrinal reason to deny communion of both kinds to the laity.

“The emperor was gravely disturbed at the arguments that prevailed in those early weeks of the Synod,” one attendee wrote in his private memoirs.

“He had sincerely hoped that there might be some grounds for collaboration—but he found himself gravely disappointed.” With arguments and infighting continuing to paralyze the synod, Charles eventually ordered a separation of the Catholic and Protestant prelates. Catholics were given over the

Abbey of St. Matthias to conduct their work, while the Protestants were given the

Liebfrauenkirke—with the right to hold services there during their stay. The emperor provided both parties with imperial receipts; the receipts to the Catholics were primarily political questions such as:

Does the emperor have the right to nominate appointments to benefices within the whole of the empire? Questions put towards the Protestant party included a mix of theological questions regarding their confessions which had been published at Regensburg, as well as political questions. Both sides were ordered to consider what had been put before them and to render answers before the emperor in a year. This marked a failure in the Synod of Trier as a vehicle for reconciliation between the Catholics and Protestants, but it transformed into one of imperial reform, which sought to reshape the emperor’s authority over the Catholic church within the whole of the empire.

It was while at Trier that Charles received news from Hungary, that the Turkish army under the command of the sultan was preparing to attack the remaining rebel strongholds within Hungary—Vasvár, Óvár, and Sopron—all of which would open the pathway into the empire through Austria. While the border had been reinforced in the year previously, it would matter little against the full might of the Ottoman Empire. With the Synod devolving into open dysfunction, Charles focused on the troubles that might soon visit the border. An agreement with the diet held the year previously allowed Charles to order a muster of the

Reichsarmee, with the troops to be deployed into Austria. The diet had also agreed to a levying of the

Türkenhilfe to provide the emperor with funds needed to defend the empire. They extended to Charles twenty-four Roman months’ worth of revenue—a sum totaling nearly ƒ2,000,000. Charles also endeavored to gain support from the Electors—both Louis V, Count Palatine of the Rhine, and Joachim II Hektor, the Elector of Brandenburg pledged support for the emperor’s defensive plans, while the Elector of Saxony remained aloof. Further support came from princes in the southern frontier, such as the Duke of Bavaria. By May 1533, the Turks had annihilated the rebel troops in Hungary and had seized the Hungarian fortifications that lay along the border.

“Messengers have brought us news of your victory,” Queen Anna of Hungary wrote in a love note to John Zápolya.

“We are gladdened that you are safe—but even more gladdened that those who oppose you have been crushed underfoot. The princesses, your daughters[1] are beyond thrilled—Anna and Mary both beg of stories of your travels—and Mary begs that you might consider her request for an Arabian horse… it is all she can think of since she saw the sultan’s mount. Little Catherine has been unwell, but little Elizabeth is well; I am in good spirits too, for I am enceinte once again. I hope and pray that I might give you the son that you so desperately desire… be sure that your kingdom is in the safest hands whilst you go abroad—and I shall protect it with my life.” Anna would give birth to her fifth child in November of 1533—another daughter, named

Helena.

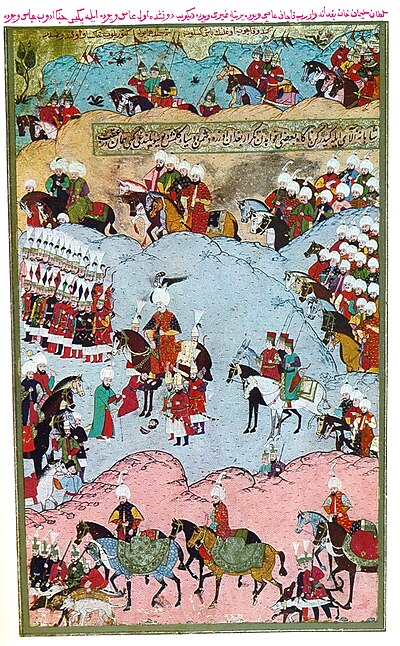

Suleiman, having crushed the Hungarian rebels, was now prepared fully to march on Germany—with Vienna, which served as a gateway upon the Danube River, as his goal. His army still numbered some 105,000 men—and included some 12,000 cavalrymen under the personal command of John Zápolya. The army remained remarkably well-provisioned thanks to Hungarian support, though rumors swirled of food shortages even in Hungary’s most prosperous region. In the southern counties, Slavonic peasants were stirred up by Marko Ševic, a Serbian military officer, who led a group of peasant rabble in a campaign of ravishment and plunder along the Ottoman-Hungarian border, targeting the lords and

aghas upon both sides of the border. The summer of 1533 proved hotter and drier than in the year before, impacting the growing season.

“The growing season of 1533 was particularly trying for our peasantry,” one magnate wrote in a letter to his grandson many years later, detailing the issues on their estate.

“Many of our peasants lost livestock to the royal officials… the most prosperous lost both their oxen and many of their sheep. Some were unable to till their personal plots; others, having lost their sheep, lost valuable income from wool and milk. The heat of the summer proved even more deadly…withering and killing crops that had already struggled to grow in our pitiful spring… even we, ensconced within the manor house could not weather this storm without issue; our debts grew, and we were even forced to seek out a loan from the neighboring estate… your grandmother was even forced to pawn several of her most valuable jewels to a Jewish pawnbroker in Világos… she would never see the jewels again…”

Ottoman painting of Janissary Recruitment.

Turkish troops arrived in Pozsony in June—putting them some eighty miles from Vienna. It was at Pozsony that John Zápolya named his wife, Anna, as

Regent of Hungary in his absence. His council was instructed to obey her as if her commands were spoken by him. Mary of Austria’s

Hofmeister, Wilhelm von Roggendorf was placed in charge of the defense of Vienna by the emperor. Charles left Trier at the beginning of June—leaving Renée in Trier as she was due to give birth at any time. Charles traveled with a sizable retinue from Trier to Regensburg, which would become his base during the Turkish incursion into the empire. By the end of June, Turkish troops had reached the walls of Vienna, and the

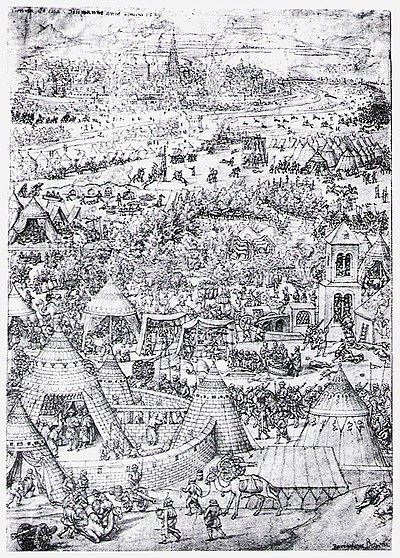

Siege of Vienna began. The great Turkish camp was pitched up outside of the walls of the city, with Suleiman ordering that his foragers despoil the surrounding countryside—both to provide his army with supplies and to deprive supplies to the Viennese. Suleiman soon discovered that the Austrians had acted before him—he found no grain or vegetables, but instead fallow fields where crops had been cut and trampled down—under the orders of Roggendorf, to deprive Suleiman of needed supplies. Though the dry summer weather had allowed Suleiman to bring forth the heavy siege guns that he would need to blast at Vienna’s walls, his army still suffered from several issues—the hot weather meant that water was in short supply, and the heat meant that there was a lack of grazing land for Turkish army’s numerous animals: many horses, oxen, and even camels had perished throughout the hot summer, and the heat had also spoiled supplies.

“Despite the tribulations, spirits remain high among the troops,” Ajas Bey—an Ottoman military officer—wrote in a letter to his favored concubine.

“We shall persevere because we are righteous—Inshallah, our sultan and Caliph shall lead us onward into paradise!” Within days, Suleiman was able to commence the shelling of the city—with the Turkish bombards firing stone and iron projectiles at Vienna’s city walls.

Aside from von Roggendorf, operational command of troops within the city went to Friedrich von Löwenstein—who led the mercenaries hired to reinforce the city. Löwenstein concerned himself with the fortification of the oldest walls of the city, near St. Stephen’s Cathedral. He also blocked off Vienna’s four city gates, and erected earthen bastions as well as a rampart within the city, in hopes of lengthening the siege on the Turkish side. The army of the Holy Roman Empire, the

Reichsarmee had been deployed away from Vienna—at Passau, upon the Danube. Given the numerical superiority of the Turkish forces, the

Reichsarmee was ordered to serve as a last defense, with some troops being dispatched to serve as raiders along the Danube—to attack Turkish supply flotillas carrying needed food, munitions, and other supplies that would be needed in a protracted siege.

“Things are going well enough,” Charles wrote in a letter to his brother, Ferdinand.

“Roggendorf continues to hold the city—he has banded together the citizens, and the reinforcements you sent last year have proven beyond helpful—the Spanish harquebusiers are an excellent shot. I only hope and pray that things continue to hold, and we shall be able to repulse the Turks from our lands.” The Turks having made landfall in Germany helped galvanize the princes in support of the emperor’s endeavor—even the Protestants looked to see the emperor succeed. Martin Luther in this period published

On War Against the Turk. In it, Luther shifted his views from those in 1518, which saw the Turks as a scourge sent by God to deal with sinning Christians—a view shared by others, such as Erasmus. In his new treatise, Luther encouraged Germans and Charles V to resist the Turk and fight against them—though his attacks upon them were still mild, with the treatise referring to the Pope once more as the anti-Christ, while Jews were described as the Devil’s Incarnate. He strongly argued that the war should be seen as a secular one, fought in self-defense, rather than a religious war to gain territory.

The siege carried into the autumn. With the surrounding farmland having been spoiled by the Austrians, the Turks were ever more reliant upon forage from further afield—as well as regular supply barges being sent up the Danube from Ottoman territory. Such barges were regularly raided by imperial troops—with some even daring to make surreptitious treks into Vienna to deliver the city's needed supplies.

“His Imperial Majesty requires further supplies,” Ibrahim Pasha, Suleiman’s Grand Vizier wrote in a letter to István Werboczy in August of 1533.

“The city proves a harder nut to crack than anticipated…but the Padishah shall prevail, as Allah wills it!” Werboczy could only forward the letter nervously to Queen Anna, with his postscript added:

“How much more can we be expected to give?” This placed Anna into a difficult situation which would prove to be her political baptism. She sent letters to the Sultan—offering up feminine flatteries while promising supplies as they could be requisitioned. Hungary’s harvest proved to be poor—and many peasants suffered under the weight of previous requisitions. Anna sought aid from her uncle in Poland—dispensing funds from the royal treasury to pay for grain imports—which were distributed to state granaries to aid the suffering peasants, rather than to supply the Turkish army. It was the Queen of Hungary’s quick thinking that kept Hungary from spiraling into further chaos—though the previous requisitions would cause economic issues and food insecurity for several years to come. Though aid was not forthcoming from Hungary, the Turks remained encamped outside Vienna—attacking the city daily with a series of bombardments, with sappers working on constructing tunnels and mines to breach the city walls. Löwenstein sent some of his men on daring raids—this included one raid where his men attempted to destroy several Ottoman mines underneath the city, which failed.

Fall of Vienna, c. 1533.

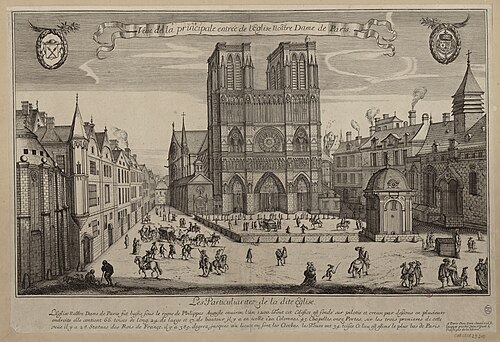

Vienna finally fell before the Ottoman troops on October 9, 1533—with Löwenstein perishing in the final assault. Wilhelm von Roggendorf was able to withdraw from the city before its collapse—along with some 3000 of the troops that had been sent in the previous year to reinforce the city. This included 250 Spanish harquebusiers under the command of Luis de Ávalos—the sole survivors of the Spanish contingent. As Roggendorf and his troops retreated towards Passau, they exacted a final revenge upon the Turkish troops—igniting a gunpowder magazine in their retreat. The explosion killed some thirty people—all civilians—and damaged the Hofburg.

“The Turks and the Hungarians indulged in an orgy after the fall of the city,” Eva Farissol—a Viennese Jewess—wrote in a private journal many years later.

“Women were torn from their homes and despoiled; the prettiest were left untouched. They were paraded before the sultan, who held court in the carnage of the Hofburg atop his golden throne. He gifted these women to his most valiant officers—who took them as slaves and concubines. The eagle atop the Stephansdom, a symbol of the emperor and his house was shorn from the cathedral and replaced with a crescent… transformed into a mosque. A muezzin was appointed into the south tower to lead the call to prayer, who sounded out across Vienna, a mournful dirge in the days following the sack…” Euphoric in his victory, Suleiman began to draw up plans for the unfinished northern tower of St. Stephen’s Cathedral to be transformed into a minaret.

“This city shall be the gem of our empire in the heart of Europe—Constantinople upon the Danube,” Suleiman declared proudly.

“The city of our forefathers has fallen,” Charles wrote in a letter to Ferdinand—undated, but probably written several days following the collapse of Vienna.

“The Reichsarmee remains in strong shape, and some 15,000 men have joined us here in Regensburg. I am resolved to march and meet this threat—this scourge of man and the Christendom can go no further.” Charles’ main concerns were for his family: he wrote firstly to Renée, ensconced at Trier with their newborn daughter, Anne. He requested that she return to the Low Countries—and invested her as

regent of the Low Countries as he had the Empress Mary. To his sister, Mary, his tone was more urgent:

“I gravely fear the Turks' next move. I doubt they will attempt to breach the mountains of Moravia or Bohemia—but you can never be sure. Be safe and remember that I am and will always remain your loving brother.” Mary herself was resolved that neither she nor her daughter would flee from Bohemia:

“We were chased from Hungary—but we shall never be chased from Bohemia. Elisabeth is the queen, and the queen must stay. And I? I shall only leave this country in a coffin, and nothing else.” Still, seeking a more defensive position, Mary and Elisabeth departed Prague for Teplitz, where they took up residence in the fortified keep that had been built by Johanna Rozmitál, George Podiebrad’s wife and queen. It was at Teplitz where Mary—as well as Elisabeth, publicly took communion in the Protestant form for the first time. Mary was also reunited with her former chaplain—Matthias Dévai Biro—who in 1527 had left her service to study under Luther at Wittenburg. Now a Protestant minister, Mary gladly accepted him back into her service, naming him as her chaplain and banishing the Catholic remnants of her religious household. The little queen’s household was not spared either, with Mary replacing her daughter’s tutor with a German theologian from Breslau, Ambrosius Moibanus.

Charles’ letters soon reached Ferdinand in Spain—where the years since his installation as Prince of Asturias and the effective Viceroy of Spain had proceeded with peace and prosperity for plenty. Spanish explorers and conquistadors continued to explore the lands beyond the Ocean Sea—one conquistador, Francisco Pizarro had led an expedition into what became known as Peru, leading his Spanish troops—as well as his Indian allies to victory against the Incan Empire at the

Battle of Huancabamba. The Incan Emperor, or

Sapa Inca Huásar who had recently triumphed[2] over his brother was captured by Spanish troops—along with his treasure train—which measured one room full of gold, and two full of silver. Despite this, Huásar and his honor guard were tortured, and Huásar was executed with a garrotte. The capital of the Incan Empire, Cuzco, fell soon after—and another native empire and its treasures fell into Spanish hands. A younger brother of Huásar, Manco, was installed as Sapa Inca—his court an empty vanity, with effective control passing into the hands of the Spanish. Huásar’s wife, Chiqui was taken as a concubine by Francisco Pizarro—and many other Incan princesses, priestesses, and noblewomen found themselves likewise abducted and despoiled by their Spanish conquerors. Ferdinand continued to work closely with his councils and the Cortes, establishing beneficial relationships with both. Many of Charles’ former Spanish advisors, such as Francisco de los Cobos had left the service of the emperor to serve the Prince of Asturias instead—as the 1530s progressed, Ferdinand’s authority became more solidified. In his martial life, the Prince of Asturias was blessed—he was devoted to his wife, the Portuguese Infanta Isabella of Portugal, and she had born him a child nearly every year. By 1533, they had five children:

Fernando Alonso (b. 1528),

Maria (b. 1529),

Isabella (b. 1530; d. 1531),

Manuel (b. 1531), and

Juan (b. 1533). Ferdinand’s marriage had been fruitful—and the Spanish line of the Habsburgs was secure.

Portrait of Huascar, c. 17th Century

Ferdinand was determined to render his brother whatever aid he could offer in his present situation—was it not the right thing to do? Though Ferdinand had reached his present position because of his hard work and ambition, it would have all been for naught had Charles not recognized that he was the correct person to govern Spain in his absence. How easy it might have been for Charles to send him elsewhere or refuse to name him as his heir—but he had. And for now, at least, Charles remained King of Spain and needed succor. Ferdinand summoned a meeting of the Cortes at

Aranjuez, with the deputies meeting at one of the local churches—with Ferdinand requesting funds from the Cortes to fund an expedition into Germany—which he planned to lead personally. Compared to Charles’ often antagonistic relationship with the Cortes of Castile, Ferdinand’s relationship proved more fruitful and productive. Aside from furnishing Ferdinand with a subsidy of 200,000 ducats, they agreed to levy the

Cruzada—an extraordinary tax that was raised in times of war. Ferdinand was prepared to furnish a troop of some 12,000 men which included not only harquebusiers but some of the first

tercio units within the Spanish army, armed with pikes and guns.

“His Majesty, the emperor, but more importantly, the King of Spain requires dire assistance to turn the tide against the Turkish hordes,” Ferdinand thundered in a speech before his troops in Barcelona in December of 1533.

“In us runs the blood of conquerors, of valiant Christian heroes—it is we who repulsed the Moslems from Granada, the Jewel of Spain. It is our fathers and grandfathers who expulsed Boabdil from Granada, sending him weeping as he crossed the seas into Africa. So too, shall we send Suleiman weeping… away from Vienna and away from Europe!”

Aside from direct military support, Ferdinand directed the Spanish navy to harass Turkish shipping and to clamp down on the Ottoman corsairs, such as Heyreddin Barbarossa who acted with impunity in the Mediterranean. The Spanish navy collaborated in this matter with the Knights of St. John—who had been granted the Ionian Islands as a new base by the Republic of Venice, in exchange for an annual tribute. The Knights of St. John would in due time become colloquially known as the

Knights of Corfu—named after the largest island as well as the largest city, which would become their new capital. Ferdinand and Spanish reinforcements would land in Trieste in April of 1534—by that time, the Turkish troops were once more on the move, having spent a harsh winter in Vienna—where sickness and deprivation had sapped and weakened the Turkish army. Aside from the troops, the animals suffered as well:

“Our supply trains have been in disarray throughout the winter,” Qarajaoglu Beg, an Ottoman officer wrote in a desperate letter to his father.

“The freezing weather has caused the Danube to freeze over in various places… everything must be carried overland. Supplies either arrive late or not at all, for the Germans continue to plunder what they can. Many animals have been slaughtered for their meat, while others have sickened from a lack of fodder. Even among the Siphais, many of them have been forced to cull their mounts due to the need…” As the winter ended and the campaign season of 1534 began, the Turkish army remained in Vienna as it awaited further supplies—detachments were sent out to forage, and raiders attacked Korneuburg and Laxenburg.

Charles in March of 1534 left his position at Regensburg for Passau, where his troops were grouped with the

Reichsarmee as well as Roggendorf’s troops—numbering some 34,000 men all.

“We are preparing to make our stand near Krems, along the Danube,” Charles wrote to Ferdinand in the spring of 1534.

“We shall await your arrival… Godspeed that your journey is without issue, and you and your men will arrive safely.” As Charles set out for Krems, Ferdinand and his troops set sail from Barcelona—they would arrive at Trieste in early May—detained for a period at Messina due to an outbreak of scurvy.

“We had little time to rest upon our arrival in Trieste,” Baltasar de Mondrágon, a Spanish soldier wrote in his memoirs.

“Our march through Carinola and Styria was arduous—I prayed daily to the Virgin Mary for deliverance, that our mission might not be in vain…” It was only in May, when rumors reached Vienna that the emperor had raised a relief force to recapture Vienna that Suleiman ordered the army mustered. The great Turkish army that had invaded Europe two years previously was in poor shape: many of the cavalrymen were lacking horses and were a desperate need of draft animals. Even Zápolya’s cavalrymen had not escaped unscathed—he’d lost nearly 5000 men—and 3000 of those to disease alone. Though Suleiman had plundered the Hofburg’s treasury, with many items sent south during the previous winter, the lack of draft animals and the need to march meant that much more of the Turks’ intended plunder was abandoned.

Among the abandoned plunder was an item of particular importance that John Zápolya managed to send back to his wife in Hungary—the Reliquary Cross that had been made for Louis I of Hungary in the 1370s—said to include pieces of the True Cross.

“I send this back to you,” Zápolya wrote in a letter to Queen Anna.

“Not because it is an object of religious devotion (you know I care not for such trifles) but because it is an important piece of our heritage. Your heritage—it belongs in Buda, not in Vienna.” Anna had the relic displayed before the court during a court sermon, which was given by János Sylvester, a recent graduate from Wittenburg.

“See the false idol before you,” Sylvester thundered from his pulpit, where he pointed dramatically at the relic.

“Catholics truly believe that such trinkets will offer them a way into the afterlife—that they must languish in purgatory until they are worthy! Faith and faith alone are what matters—Christ, our God and Lord died for our sins, and was risen again for our justification.” Before the whole of the court, Sylvester smashed the reliquary—pointing to the pieces of wood scattered amongst the broken crystal and gilt.

“These are no pieces from the cross of Our Lord—merely cuttings from a branch—and more proof of the lies of the false church and their false prophets!” Sylvester's speech was highly appreciated—and marked the beginning of Hungary’s shift towards the Protestant faith.

Suleiman in Austria, c. 1534.

By early May, Ferdinand and his relief force reached Krems, where they were able to rendezvous with Charles’ troops. The combined forces at Krems numbered nearly 46,000 men—along with some 120 artillery pieces. Charles ordered the army encamped outside of Krems, and scouts sent out by an imperial commander, Johann Katzianer soon reported that the Turks were encamped near Tulln, some forty miles from Krems. In a war council before Charles and Ferdinand, two different viewpoints were argued: some, such as Katzianer, argued that their position should be improved at Krems and they pursued a defensive war against the Turks. Others, such as Roggendorf, argued that the Turkish army had suffered grave losses since their capture of Vienna—and each mile took them further away from Turkish territory, making the resupply of the army ever more difficult. Roggendorf argued that their best bet was a surprise offensive against the Turks—if they were successful, they would be able to give the Turks not only the black eye that they deserved but earn a vital victory for the emperor and the empire, too. Ferdinand deferred to Charles, telling the emperor that:

“You are in command here—and it is your word that is law. If you believe the defense shall lead us to victory, then let us defend Krems with every drop of blood. However, if you firmly believe our path is through the offensive, then let us march.” It was an easy choice for the emperor: the Turks had already marched a mile too far into his dominions. He would take the war to them, and he would succeed.

The imperial army came upon the Turkish troops near the hamlet of Grafenwörth on May 27th, 1534. The

Battle of Grafenwörth, as it became known, broke out in the early morning hours when the imperial army set upon the Turks as they were breaking down their camp, taking them by complete surprise. The Turkish cavalry was demoralized and many of them without mounts, were unable to effectively counter the imperial cavalry charge, which opened the battle.

“The imperial cavalry charge cut through the Moslems like butter—their sabers creating a sea of red upon the early morning soil,” an imperial soldier wrote in his journals.

“The Turks were disorganized… while the Hungarian cavalry attempted to counter against our attack, they soon met the volley of the imperial artillery, which added skin, bone, and viscera to the growing pools of blood…” Grafenwörth lasted only two hours, with Sultan Suleiman, with his army in poor shape, chose to withdraw his troops from the field. The imperial army suffered only 2000 casualties—with Sultan Suleiman losing some 6000 men, with another 3000 taken hostage. John Zápolya’s troops suffered most heavily—over half of his cavalrymen were lost in battle, and a further 1500 were captured in battle. While Grafenwörth was no huge turning point in Ottoman ambitions in Europe—their losses in battle had been minimal—it represented an important propaganda victory for Christian Europe: the Turks were not unstoppable, and their offense into Europe could be contained.

Following the defeat at Grafenwörth, the Turkish army retreated through Vienna into Hungary—the Turkish army in tatters as it did so.

“When the Padishah retreated to Buda following the retreat from Grafenwörth, his mood was dark and foul… he was curt with King of Hungary—and short. He demanded ƒ60,000 from the Hungarian treasury in exchange—the annual tribute which was owed for the past two previous years,” a historian of the period wrote.

“The Hungarian treasury, impoverished by its previous support of the Sultan was in little position to pay what was owed, with King John offering ƒ15,000 immediately with the promises of more. This did not please the Sultan, who reportedly told the king ‘If I cannot be given what I am owed, then it must be taken.’ The Padishah left Buda soon after—but only with the 15,000 which King John could pay.” Suleiman soon made good upon his promise to Zápolya—he introduced Turkish troops into Hungary, who occupied Osijek, Pétérvárad, and Temesvár, as well as several other Hungarian fortifications along the border. Aside from this, Suleiman ordered a janissary regiment garrisoned in Buda Castle—ostensibly this was a gift from the Sultan for the protection of an esteemed ally and friend—but in reality, all knew it was meant to keep Hungary and its king in line.

[1] Made some changes to the names I proposed previously.

[2] IOTL, Huásar was killed by Atahualpa.