Germany AND Italy? So the HRE?Nope! Your original guess was much closer. Just off by one word.

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Anno Obumbratio: A 16th Century Alternate History

- Thread starter DrakeRlugia

- Start date

Threadmarks

View all 53 threadmarks

Reader mode

Reader mode

Recent threadmarks

Chapter 40. Memoriae Sacrum Addenum: Additional AI Portraits / Images Chapter 41. Rogues of Italy Chapter 42. The Imperial Division Chapter 43. The Council of Lucerne Chapter 44. The Fürstenkrieg — The Italian War of 1555-1562; Part 1. Chapter 45. An English Rose (With Thorns) Addendum: Dynastic Trees (Updated to 1559)You are the closest. My lips are sealed. 😉Germany AND Italy? So the HRE?

I'm gonna guess some sort of centralized HRE or at least, a HRE where the majority of the estates follow the Emperor and may or may not have Denmark in the lot tooYou are the closest. My lips are sealed. 😉

Burgundian Italy!😉Germany or Italy.

Chapter 38. The Bruderkrieg / War of the League of Mühlhausen

Chapter 38. The Bruderkrieg / War of the League of Mühlhausen

1545-1548; Germany.

“Thus, we shall judge the emperor in this case, not to be the emperor, but a soldier and mercenary of the Pope.”

— Martin Luther

Musical Accompaniment: Vecchie Letrose

Map of the Holy Roman Empire, 1547.

The seeds for the War of the League of Mühlhausen, better known as the Bruderkrieg in German, were laid in the aftermath of the Italian War of 1542-44 through the Treaty of Compiègne. Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor, had conceded to the Protestants on some matters to prosecute the war, but many were fearful of his true intentions in the aftermath. Soon after the end of the war, Charles entered negotiations with Pope Gelasius III to open a general church council in Bologna (which received tepid support from François), along with a secret promise to provide funding should war break out against the Protestants. In the east, Charles negotiated a truce with the Ottomans. The Truce of Adrianople forced Charles and his son Maximilian to recognize Ottoman control over Hungary. In return, they were allowed to retain western and northern districts in Hungary that had rallied to Elisabeth of Bohemia—in exchange for a yearly payment of ƒ30,000. This breathing room also allowed Charles to reaffirm his ties to Catholic princes within the empire: the Duchy of Saxony, once held by the steadfastly Protestant Heinrich the Pious, had been succeeded in 1541 by his sole surviving son, Severin—who had been reared as a Catholic at the imperial court. In 1545, Severin married Anna Gennara of Savoy, the emperor’s niece. Martin Luther, a man in failing health, was the sole glue that held the Protestant camp together.

Luther, who had begun suffering from ill health in the 1530s, passed away in February 1546. He was interned in the Schlosskirche in Wittenberg at the front of the pulpit. With his death, the last restraint upon the Protestant Princes was lifted: no longer would they need to listen to Luther’s moral and legal reasons to avoid war with the emperor, nor his entreaties that they should resist his demands. For the League of Mühlhausen, they saw a dangerous foe in the emperor, a man who had never kept his word to them. They had no interest in attending the new Papal council that would soon open. Rather than be caught unaware, members of the League agreed to meet at Saalfeld in July 1546 to decide how they would respond militarily to the emperor. “The emperor has greater resources, that is true,” Philip of Hesse argued before the meeting of the princes. “But we are of quicker wit… we can mobilize our forces quicker than the emperor can raise his. We must strike—deal a preventative blow before he can quash us beneath his feet.” At Saalfeld, the Protestants decided that the emperor must be struck down as quickly as possible. They relied upon Luther’s idea of a Beerwolf—that the emperor had violated the political contract between himself and the princes, giving them the right to take military action. The spark that lit the fires of war began in Hesse when Protestant troops occupied the city of Gersfeld—a Catholic city attached to the territories of the Princely Abbey of Fulda. “They wasted little time in pillaging the city,” one historian wrote of the early days of the conflict. “They looted the homes of the residents, but their greatest travesty was Gerfeld’s church… the troops stripped it of its Catholic ornaments. Afterward, they hosted a bonfire, forcing the citizenry to watch as the so-called relics of idolatry were burnt.”

News of this atrocity soon reached the emperor, who had taken up residence once more in Brussels. He conferred with his counsellors, who at this epoch included Nicholas Perrenot, Arianitto Comène—known also as Arianitto Cominato—Viglius van Ayatta, and Louis of Praet. The imperial council urged a proactive response to the crisis, believing that this represented a chance for Charles to deal a militant blow against the Protestant Princes. “His Majesty has decided to place an imperial ban upon the league,” Empress Renée wrote in a letter to her confidant, Michelle Saubonne. “He intends to march against them… I am twisted in knots… a traitor to my faith if I am silent, a traitor to my husband if I speak. I must suffer in silence and hope for better days.” Renée and Charles’ relations had cooled down by the 1540s following the birth of their last child. There were tensions from their clashing personalities and Renée’s growing faith, which she kept a secret. In 1545, the Inquisitor General of the Low Countries, Ruard Tapper, questioned several of her servants. Several of Renée’s French servants were found to possess Protestant tracts and were proclaimed guilty of heresy. Tapper, a lenient man who believed that spiritual issues needed spiritual solutions, imposed penances upon those guilty. Clément Marot, Renée’s secretary, formally abjured his Protestant faith—but died shortly after, some believed from shock. The scandal forced Charles to intervene. He banished Anne’s French servants, who were ordered to return to France despite Renée’s fierce protestations. When Charles ordered Renée’s own chambers searched, it was discovered that she used a secret compartment within one of her chests to hide not only Protestant tracts but letters that she had received from Jean Calvin and Philip Melanchthon, which made clear her steadfast faith. “We shall deal with this matter in due course,” Charles allegedly uttered coldly to Renée when her secret was discovered. Charles sternly ordered Renée to retire to Mechelen, where she was given the former residence of Margaret of York, the Hof van York. Renée was also forbidden to take the children: Charles retained custody of their three daughters, Anne, Adélaïde, and Michèle, as well as their two sons, Charles, and Jean. This meant an effective end to their relationship and marriage; never again would Charles and Renée live under the same roof. For now, the emperor had a greater focus than his heretic wife—he commanded none to speak of it.

Severinus/Severin, Duke of Saxony; AI Generated.

Charles brought together an army of some 50,000 men—this included not only 25,000 Germans but some 15,000 troops from the Low Countries, and some 15,000 men loaned to him: comprised of 10,000 English troops under the personal command of King John. Prince Ferdinand promised some 5,000 men—remnants of the force that had invaded Naples, but their arrival was uncertain. Charles’ son also pledged to provide some 13,000 troops from Bohemia if needed. In July 1546, Charles formally placed both Philip of Hesse and Johann Friedrich of Saxony under an imperial ban, relating to their actions in Wölfenbuttel, where they had deposed the duke, Heinrich V. Charles was able to gather his army with relatively little trouble at Leuven. The emperor was aided in this by Duke Severin of Saxony, who used the support of Maximilian in Bohemia to initiate an invasion of the Electorate of Saxony in October 1546. “I have given the duke all the aid that he desires,” Maximilian wrote in a letter to his father. “The diet has not exactly been as liberal with funding as I have hoped—but we shall render all the aid he needs to succeed.” Johann Friedrich was soon forced to abandon his position in Hesse to return to Saxony, where he succeeded in liberating his territories. By the fall, Johann Friedrich launched a counterattack into the Albertine Saxon lands held by Duke Severin and the adjacent lands within the Kingdom of Bohemia. As the weather turned colder and snow coated the empire, campaigning stopped for the year. Charles wintered in Mainz with his nephew John. “There is naught but ice and snow everywhere we look,” John wrote in a letter to Mary. “We have been in Mainz for nearly a fortnight now, and a terrible storm rolled through overnight. The city is covered in snow, a frozen idol awaiting the warmth of spring. Continue to care for yourself and our children; I was most gladdened to hear in your last letter that little York and Somerset continue to thrive, and that Isabella has recovered from her fever.”

Campaigning resumed in early 1547. Charles was able to capture several Lutheran imperial cities, such as Frankfurt. Some princes that supported the League of Mühlhausen, such as Duke Ulrich of Württemberg and Friedrich II, the Count Palatine of the Rhine, chose to submit to the emperor rather than fight. Imperial forces moved quickly into the domains of Philip of Hesse, where the Hessian troops were dealt a brutal blow at the Battle of Gießen. “Gießen marked a drastic change in the ambitions of Philip of Hesse,” one 18th-century historian wrote in his treatise about the Bruderskrieg. “Imperial troops had rapidly overrun his domains, and the landgrave had no choice but to throw himself before the emperor. Emperor Charles V granted the rebel an interview near Laubach; he begged plainly for mercy: that his domains were to remain intact and that he should be freed. The emperor thought differently and ordered the landgrave to be closely confined. He was eventually transferred to the citadel near Namur, where he would await his fate…” The collapse of the Hessian forces dealt a significant blow to Johann Friedrich’s position and the League’s. “Johann Friedrich hoped vainly that the Bohemian Protestants might rise up and aid his cause,” another historian wrote. “He discovered quickly that the Bohemians, with their rights protected and affirmed under their new king, had no interest in joining a rebel movement that was fast losing steam.” By April 1547, imperial troops had reached Saxony—joined by men from the Duke of Severin’s army. Johann Friedrich’s troops came to rest Köttlitz—he had divided his army, with a significant amount dispatched to prevent Bohemian soldiers from joining the imperial army. He had also expended an incredible amount of manpower to garrison cities and towns in southern Saxony—leaving only a small number of troops to cover the Elbe River, which he considered too significant for the imperial army to cross.

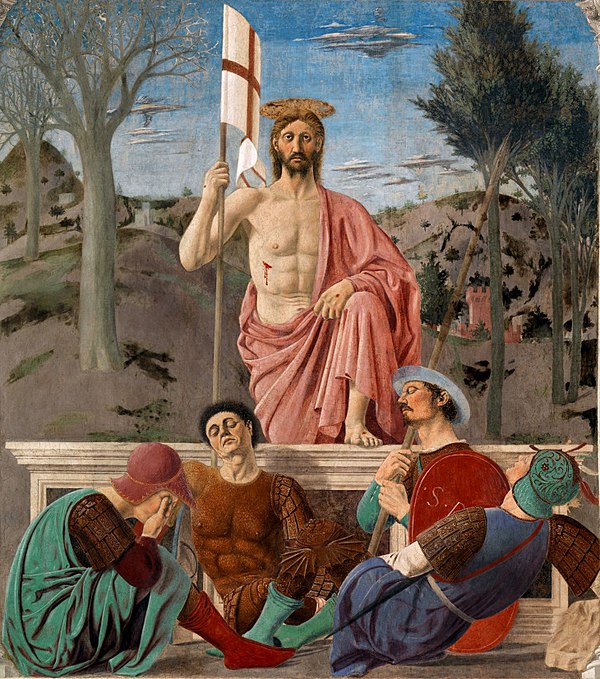

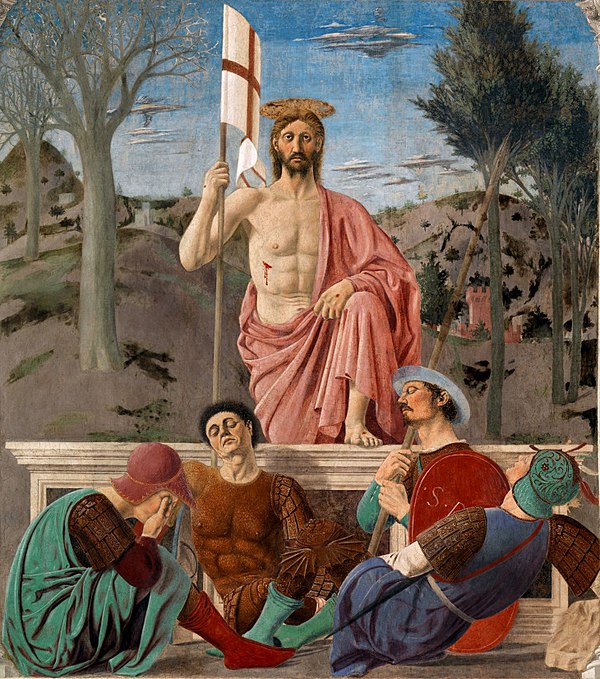

Mercy after the Battle of Gießen, Engraving.

Charles first reached the Elbe River on the evening of May 4, 1547. Many of his generals, such as the Prince of Orange, cautioned the emperor against engaging Saxon troops on the other side. On the other hand, John, the King of England, argued that he needed to take drastic action to take the Saxons by surprise. The following day, several members of the advance guard of the imperial army looked for a way to cross the Elbe. “The guards along the Elbe proved a thorn in the emperor’s side—should they be alerted or know of the imperial crossing; all advantage would be lost.” In the twilight of the following day, before the sun had risen, the emperor ordered part of the imperial advance guard to advance to find a way to cross. Small groups of troops swam across the river, taking the Saxon guards by surprise under the cover of darkness. Meanwhile, John used the help of a local farmer to find a place within the river that would allow the whole army to ford through the river—while English longbowmen, in one of the final battles they participated in, helped prevent the destruction of a pontoon bridge. This allowed the imperial cavalry to pass safely across to the shore. The entire army finished its crossing by late afternoon—with Johann Friedrich completely unaware.

The Battle of Köttlitz broke out on the evening of May 5, 1547. Of Charles’ entire army, he possessed some 25,000 men—including his Burgundian and German levies, English troops under John, and a small contingent of Hungarian cavalry sent by Maximilian that had bypassed the Saxon guards. Johann Friedrich’s army of 11,000 consisted primarily of peasant levies, but they were prepared to stand their ground and fight for their faith. Charles suffered an attack of gout on the day of battle—he was carried to the battlefield in a litter but extorted his troops: “We fight for the true faith—our holy mother church!” The first cavalry assaults were led by King John of England—including his English cavalry and the Hungarian sortie the emperor had placed under his command. “John II of England rode forth gloriously,” Charles Wriothesley wrote in his chronicle. “A ghost has risen from Thérouanne; the young king continued where his predecessor had started. The Hungarians failed in the first charge, and the young king was nearly hit—a stray shot merely grazing his ear. The king commanded the right flank, comprised of the finest English cavalry… a second charge against the Protestant’s weaker flank helped the king deliver victory—and the field, to the emperor. Cries of ‘For St. George! For England!’ mingled with those praising the emperor in French and German amongst sundry other tongues…” The battle proved a complete rout—the enemy troops were scattered into the woodworks, and Johann Friedrich, the Elector of Saxony, was soon taken prisoner, having been wounded in the face. When news of his victory was delivered to the emperor, he had only one thing to say: “Je suis venu, j’ai vu, Dieu a vaincu.” John and his English forces would depart from Germany following this final victory—returning home to England by the end of 1547.

Imprisoned, Johann Friedrich was now at the emperor’s mercy. Condemned in a court-martial, the elector was sentenced to death. Johann’s wife, Sybille of Cleves, still held Wittenberg and was prepared to defend the city to her last breath. As the imperial army was prepared to lay siege to the Saxon capital, Johann Friedrich was offered an option to receive a reprieve. Johann Friedrich signed the Capitulation of Wittenburg in June 1547—resigning the electoral dignity to Duke Severin of Saxony as well as a significant portion of his territories, leaving Johann with only a piece of the Ernestine lands around Gotha, Weimar, and Coburg. In signing the agreement, Johann Friedrich’s punishment was commuted to a life sentence, and he to be imprisoned in Namur alongside Philip of Hesse. “Wittenberg, the cradle of the Reformation, fell easily enough in the hands of the imperial forces.” Andreas Chyträus wrote of the fall of Wittenburg. “Duke Severin of Saxony was formally granted the electoral dignity at Wittenberg Castle, and a celebratory Catholic mass was held shortly after that—perhaps the first in twenty years in Wittenberg.” Saxony’s realignment meant that one more secular elector joined the Catholic camp—leaving the Count Palatine as the sole Protestant. The fall of Wittenberg into the hands of the Catholic party was a profound shock that caused many reformers to lament. The Prince of Orange, one of the emperor’s imperial commanders, suggested Martin Luther be disinterred from his resting place in the Schlosskirche. However, Charles dissuaded him: “He is dead; there is no reason to disturb him now.”

Emperor Charles V at Köttlitz; Titian, painted c. 1548.

The League of Mühlhausen essentially collapsed following Johann Friedrich’s defeat. Some holdouts in northern Germany remained, and imperial troops under the command of Eric II, Prince of Calenberg, were ordered to deal with them. He had support from the Hanseatic City of Lübeck, which contributed significantly to the imperial victory at the Battle of Adendorf, which allowed imperial authority to flourish in northern Germany once Calenberg’s army occupied Bremen. The Bruderkrieg, which had begun with a boom, now ended in a small whimper. The city of Magdeburg, one of the last remaining holdouts against the emperor, conceded to imperial demands and agreed to pay the fines that would be levied against the city. “Charles V emerged victorious from the Bruderkrieg,” one historian would write. “But the Protestant faith was a pandora’s box—twenty years past, it was far too late to push it back into the box. But Charles, often hounded and suffering losses during his time as emperor, had succeeded where his grandfather and forefathers had failed—he had secured a victory over the princes who oft stood in the way of change… giving the emperor a unique chance to secure his position—both for himself and for the House of Habsburg.” Not long after securing his victory over the Protestants, Charles called for an imperial diet to be assembled at Augsburg. Rather than returning to the Low Countries, Charles declared that he would settle in Innsbruck to await the start of the diet. Refurbishments were ordered to the Innsbruck Hofburg.

The Diet of Augsburg opened in 1548—while known in some circles as the Diet of Reforms, others derided it as the Iron Diet due to the tense atmosphere that pervaded inside it—primarily because of the emperor’s military force that controlled the diet from the outside. Aside from Charles, Maximilian and Elisabeth attended the diet, allowing Charles to meet his daughter-in-law for the first time. “His Majesty was the perfect gentleman,” one courtier wrote. “It was as if he was twenty years younger and speaking with his beloved Mary yet again.” The diet opened with routine business: Charles announced plans for Maximilian’s election as King of Romans, with the election to be held in the next year in Frankfurt. From there, Charles asked that his chancellor read his intentions for the diet and the empire: articles that would become known as the Reformatio Imperii. The first options were primarily administration: part one concerned the Reichsregiment, which was to be reformed into the Fürstenregiment, a princely council based in Brussels that would be given some distinct organizational functions for the first time. Compared to the Reichsregiment of Maximilian’s time, the Fürstenregiment was to be dominated by the emperor, who would not only serve as chairman but hold final approval for all decisions made by the Fürstenregiment. Secondly, Charles called for the Geheimer Pfennig to be permanently levied to fund the Fürstenregiment alongside the Kammerzieler, which paid for the Imperial Chamber Court and the Römermonat concerning collections for the imperial army. Like the previously mentioned tax, the imperial treasurer would handle the disbursement of the funds, with collections to be handled through the imperial circles.

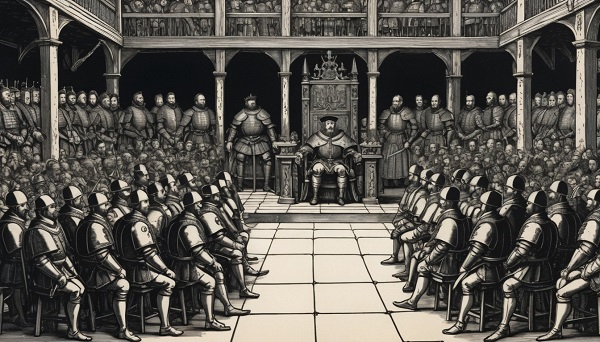

Woodcut of the Diet of Augsburg, 1548—Soldiers stand prepared behind the emperor; AI Generated.

Other reforms were financial—mint regulations to help introduce economic parity between the different parts of Germany, standardize the coinage and help prevent debasement. Expansion of the Imperial postal service was ordered, with additional routes planned throughout Germany to truly connect the imperial capital in Brussels to the rest of the empire. Others were administrative—such as the reorganization of the Burgundian Imperial Circle to include the Duchy of Guelders, the County of Zutphen, and the territories of Utrecht, Groningen, Overjissel, and the County of Drenthe. The whole Burgundian inheritance and its expanded territories would be covered for the first time in one imperial circle. The Low Countries would remain attached to the Imperial Chamber Court’s jurisdiction and pay taxes equivalent to two electorates. Its war taxes would be comparable to three electorates. The final and most important reforms that Charles considered as part of his program concerned the territorial makeup within the empire, but primarily considering his own hereditary domains. The Reformatio Imperii decreed changes in the electoral challenge—Bohemia was to lose its electoral vote within the Electoral College; in exchange, the kingdom’s unique position and connection to the empire would be recognized as an imperial dependency—which came along with freedom from future imperial laws. One attendee wrote: “All waited for bated breath as the archchancellor spoke… his droning voice as he degreed that Bohemia’s vote—already in the hands of the House of Habsburg would instead pass to Burgundy…”

The most significant changes concerned the Burgundian inheritance in the Low Countries. In decreeing the transfer of the Bohemian vote to Burgundy, the Reformatio Imperii revived the use of a title already used by the Holy Roman Emperors—that of the so-called Kingdom of Burgundy, sometimes known as the Kingdom of Arles, that had existed in Provence. This kingdom would be spun off as an electorate, now to contain the Burgundian inheritance in the Low Countries—thus shifting Bohemia’s vote onto Burgundy. As part of the electoral inheritance law, this act helped further centralize the Burgundian Low Countries, ensuring they would remain together and be inherited by a single person. Another section concerned the Privilegium Maius that had allegedly made Austria an Archduchy—with Charles decreeing the children of his line would bear the title of Prince/Princess of Burgundy ahead of that of Archduke/Archduchess of Austria. Other changes concerned territorial adjustments for those of proven loyalty: Saxony, as mentioned, had passed to Severin, who had reduced the former electoral line to a tiny cluster of land. Brandenburg was allowed to absorb several districts within its domains—though not Magdeburg. Other victors were the spiritual electors and certain ecclesiastical principalities—which saw organizations of lands and territories within their favor, to make them stronger redoubts of the Catholic faith—while also increasing imperial power through the Concordat of Aix-la-Chapelle. The last statements concerned religion, and the Archchancellor was apparent as he spoke: “The emperor asks that the Protestants behave quietly and cause no trouble; he is prepared to recognize their married clergy and the laity to receive communion of both kinds. He asks that the Protestants prepare a delegation to attend the Council of Bologna as soon as possible. If reconciliation is not truly possible, then the emperor is willing to be magnanimous in his reforms.” Some could not help but genuinely wonder—what exactly did that mean?

1545-1548; Germany.

“Thus, we shall judge the emperor in this case, not to be the emperor, but a soldier and mercenary of the Pope.”

— Martin Luther

Musical Accompaniment: Vecchie Letrose

Map of the Holy Roman Empire, 1547.

The seeds for the War of the League of Mühlhausen, better known as the Bruderkrieg in German, were laid in the aftermath of the Italian War of 1542-44 through the Treaty of Compiègne. Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor, had conceded to the Protestants on some matters to prosecute the war, but many were fearful of his true intentions in the aftermath. Soon after the end of the war, Charles entered negotiations with Pope Gelasius III to open a general church council in Bologna (which received tepid support from François), along with a secret promise to provide funding should war break out against the Protestants. In the east, Charles negotiated a truce with the Ottomans. The Truce of Adrianople forced Charles and his son Maximilian to recognize Ottoman control over Hungary. In return, they were allowed to retain western and northern districts in Hungary that had rallied to Elisabeth of Bohemia—in exchange for a yearly payment of ƒ30,000. This breathing room also allowed Charles to reaffirm his ties to Catholic princes within the empire: the Duchy of Saxony, once held by the steadfastly Protestant Heinrich the Pious, had been succeeded in 1541 by his sole surviving son, Severin—who had been reared as a Catholic at the imperial court. In 1545, Severin married Anna Gennara of Savoy, the emperor’s niece. Martin Luther, a man in failing health, was the sole glue that held the Protestant camp together.

Luther, who had begun suffering from ill health in the 1530s, passed away in February 1546. He was interned in the Schlosskirche in Wittenberg at the front of the pulpit. With his death, the last restraint upon the Protestant Princes was lifted: no longer would they need to listen to Luther’s moral and legal reasons to avoid war with the emperor, nor his entreaties that they should resist his demands. For the League of Mühlhausen, they saw a dangerous foe in the emperor, a man who had never kept his word to them. They had no interest in attending the new Papal council that would soon open. Rather than be caught unaware, members of the League agreed to meet at Saalfeld in July 1546 to decide how they would respond militarily to the emperor. “The emperor has greater resources, that is true,” Philip of Hesse argued before the meeting of the princes. “But we are of quicker wit… we can mobilize our forces quicker than the emperor can raise his. We must strike—deal a preventative blow before he can quash us beneath his feet.” At Saalfeld, the Protestants decided that the emperor must be struck down as quickly as possible. They relied upon Luther’s idea of a Beerwolf—that the emperor had violated the political contract between himself and the princes, giving them the right to take military action. The spark that lit the fires of war began in Hesse when Protestant troops occupied the city of Gersfeld—a Catholic city attached to the territories of the Princely Abbey of Fulda. “They wasted little time in pillaging the city,” one historian wrote of the early days of the conflict. “They looted the homes of the residents, but their greatest travesty was Gerfeld’s church… the troops stripped it of its Catholic ornaments. Afterward, they hosted a bonfire, forcing the citizenry to watch as the so-called relics of idolatry were burnt.”

News of this atrocity soon reached the emperor, who had taken up residence once more in Brussels. He conferred with his counsellors, who at this epoch included Nicholas Perrenot, Arianitto Comène—known also as Arianitto Cominato—Viglius van Ayatta, and Louis of Praet. The imperial council urged a proactive response to the crisis, believing that this represented a chance for Charles to deal a militant blow against the Protestant Princes. “His Majesty has decided to place an imperial ban upon the league,” Empress Renée wrote in a letter to her confidant, Michelle Saubonne. “He intends to march against them… I am twisted in knots… a traitor to my faith if I am silent, a traitor to my husband if I speak. I must suffer in silence and hope for better days.” Renée and Charles’ relations had cooled down by the 1540s following the birth of their last child. There were tensions from their clashing personalities and Renée’s growing faith, which she kept a secret. In 1545, the Inquisitor General of the Low Countries, Ruard Tapper, questioned several of her servants. Several of Renée’s French servants were found to possess Protestant tracts and were proclaimed guilty of heresy. Tapper, a lenient man who believed that spiritual issues needed spiritual solutions, imposed penances upon those guilty. Clément Marot, Renée’s secretary, formally abjured his Protestant faith—but died shortly after, some believed from shock. The scandal forced Charles to intervene. He banished Anne’s French servants, who were ordered to return to France despite Renée’s fierce protestations. When Charles ordered Renée’s own chambers searched, it was discovered that she used a secret compartment within one of her chests to hide not only Protestant tracts but letters that she had received from Jean Calvin and Philip Melanchthon, which made clear her steadfast faith. “We shall deal with this matter in due course,” Charles allegedly uttered coldly to Renée when her secret was discovered. Charles sternly ordered Renée to retire to Mechelen, where she was given the former residence of Margaret of York, the Hof van York. Renée was also forbidden to take the children: Charles retained custody of their three daughters, Anne, Adélaïde, and Michèle, as well as their two sons, Charles, and Jean. This meant an effective end to their relationship and marriage; never again would Charles and Renée live under the same roof. For now, the emperor had a greater focus than his heretic wife—he commanded none to speak of it.

Severinus/Severin, Duke of Saxony; AI Generated.

Charles brought together an army of some 50,000 men—this included not only 25,000 Germans but some 15,000 troops from the Low Countries, and some 15,000 men loaned to him: comprised of 10,000 English troops under the personal command of King John. Prince Ferdinand promised some 5,000 men—remnants of the force that had invaded Naples, but their arrival was uncertain. Charles’ son also pledged to provide some 13,000 troops from Bohemia if needed. In July 1546, Charles formally placed both Philip of Hesse and Johann Friedrich of Saxony under an imperial ban, relating to their actions in Wölfenbuttel, where they had deposed the duke, Heinrich V. Charles was able to gather his army with relatively little trouble at Leuven. The emperor was aided in this by Duke Severin of Saxony, who used the support of Maximilian in Bohemia to initiate an invasion of the Electorate of Saxony in October 1546. “I have given the duke all the aid that he desires,” Maximilian wrote in a letter to his father. “The diet has not exactly been as liberal with funding as I have hoped—but we shall render all the aid he needs to succeed.” Johann Friedrich was soon forced to abandon his position in Hesse to return to Saxony, where he succeeded in liberating his territories. By the fall, Johann Friedrich launched a counterattack into the Albertine Saxon lands held by Duke Severin and the adjacent lands within the Kingdom of Bohemia. As the weather turned colder and snow coated the empire, campaigning stopped for the year. Charles wintered in Mainz with his nephew John. “There is naught but ice and snow everywhere we look,” John wrote in a letter to Mary. “We have been in Mainz for nearly a fortnight now, and a terrible storm rolled through overnight. The city is covered in snow, a frozen idol awaiting the warmth of spring. Continue to care for yourself and our children; I was most gladdened to hear in your last letter that little York and Somerset continue to thrive, and that Isabella has recovered from her fever.”

Campaigning resumed in early 1547. Charles was able to capture several Lutheran imperial cities, such as Frankfurt. Some princes that supported the League of Mühlhausen, such as Duke Ulrich of Württemberg and Friedrich II, the Count Palatine of the Rhine, chose to submit to the emperor rather than fight. Imperial forces moved quickly into the domains of Philip of Hesse, where the Hessian troops were dealt a brutal blow at the Battle of Gießen. “Gießen marked a drastic change in the ambitions of Philip of Hesse,” one 18th-century historian wrote in his treatise about the Bruderskrieg. “Imperial troops had rapidly overrun his domains, and the landgrave had no choice but to throw himself before the emperor. Emperor Charles V granted the rebel an interview near Laubach; he begged plainly for mercy: that his domains were to remain intact and that he should be freed. The emperor thought differently and ordered the landgrave to be closely confined. He was eventually transferred to the citadel near Namur, where he would await his fate…” The collapse of the Hessian forces dealt a significant blow to Johann Friedrich’s position and the League’s. “Johann Friedrich hoped vainly that the Bohemian Protestants might rise up and aid his cause,” another historian wrote. “He discovered quickly that the Bohemians, with their rights protected and affirmed under their new king, had no interest in joining a rebel movement that was fast losing steam.” By April 1547, imperial troops had reached Saxony—joined by men from the Duke of Severin’s army. Johann Friedrich’s troops came to rest Köttlitz—he had divided his army, with a significant amount dispatched to prevent Bohemian soldiers from joining the imperial army. He had also expended an incredible amount of manpower to garrison cities and towns in southern Saxony—leaving only a small number of troops to cover the Elbe River, which he considered too significant for the imperial army to cross.

Mercy after the Battle of Gießen, Engraving.

Charles first reached the Elbe River on the evening of May 4, 1547. Many of his generals, such as the Prince of Orange, cautioned the emperor against engaging Saxon troops on the other side. On the other hand, John, the King of England, argued that he needed to take drastic action to take the Saxons by surprise. The following day, several members of the advance guard of the imperial army looked for a way to cross the Elbe. “The guards along the Elbe proved a thorn in the emperor’s side—should they be alerted or know of the imperial crossing; all advantage would be lost.” In the twilight of the following day, before the sun had risen, the emperor ordered part of the imperial advance guard to advance to find a way to cross. Small groups of troops swam across the river, taking the Saxon guards by surprise under the cover of darkness. Meanwhile, John used the help of a local farmer to find a place within the river that would allow the whole army to ford through the river—while English longbowmen, in one of the final battles they participated in, helped prevent the destruction of a pontoon bridge. This allowed the imperial cavalry to pass safely across to the shore. The entire army finished its crossing by late afternoon—with Johann Friedrich completely unaware.

The Battle of Köttlitz broke out on the evening of May 5, 1547. Of Charles’ entire army, he possessed some 25,000 men—including his Burgundian and German levies, English troops under John, and a small contingent of Hungarian cavalry sent by Maximilian that had bypassed the Saxon guards. Johann Friedrich’s army of 11,000 consisted primarily of peasant levies, but they were prepared to stand their ground and fight for their faith. Charles suffered an attack of gout on the day of battle—he was carried to the battlefield in a litter but extorted his troops: “We fight for the true faith—our holy mother church!” The first cavalry assaults were led by King John of England—including his English cavalry and the Hungarian sortie the emperor had placed under his command. “John II of England rode forth gloriously,” Charles Wriothesley wrote in his chronicle. “A ghost has risen from Thérouanne; the young king continued where his predecessor had started. The Hungarians failed in the first charge, and the young king was nearly hit—a stray shot merely grazing his ear. The king commanded the right flank, comprised of the finest English cavalry… a second charge against the Protestant’s weaker flank helped the king deliver victory—and the field, to the emperor. Cries of ‘For St. George! For England!’ mingled with those praising the emperor in French and German amongst sundry other tongues…” The battle proved a complete rout—the enemy troops were scattered into the woodworks, and Johann Friedrich, the Elector of Saxony, was soon taken prisoner, having been wounded in the face. When news of his victory was delivered to the emperor, he had only one thing to say: “Je suis venu, j’ai vu, Dieu a vaincu.” John and his English forces would depart from Germany following this final victory—returning home to England by the end of 1547.

Imprisoned, Johann Friedrich was now at the emperor’s mercy. Condemned in a court-martial, the elector was sentenced to death. Johann’s wife, Sybille of Cleves, still held Wittenberg and was prepared to defend the city to her last breath. As the imperial army was prepared to lay siege to the Saxon capital, Johann Friedrich was offered an option to receive a reprieve. Johann Friedrich signed the Capitulation of Wittenburg in June 1547—resigning the electoral dignity to Duke Severin of Saxony as well as a significant portion of his territories, leaving Johann with only a piece of the Ernestine lands around Gotha, Weimar, and Coburg. In signing the agreement, Johann Friedrich’s punishment was commuted to a life sentence, and he to be imprisoned in Namur alongside Philip of Hesse. “Wittenberg, the cradle of the Reformation, fell easily enough in the hands of the imperial forces.” Andreas Chyträus wrote of the fall of Wittenburg. “Duke Severin of Saxony was formally granted the electoral dignity at Wittenberg Castle, and a celebratory Catholic mass was held shortly after that—perhaps the first in twenty years in Wittenberg.” Saxony’s realignment meant that one more secular elector joined the Catholic camp—leaving the Count Palatine as the sole Protestant. The fall of Wittenberg into the hands of the Catholic party was a profound shock that caused many reformers to lament. The Prince of Orange, one of the emperor’s imperial commanders, suggested Martin Luther be disinterred from his resting place in the Schlosskirche. However, Charles dissuaded him: “He is dead; there is no reason to disturb him now.”

Emperor Charles V at Köttlitz; Titian, painted c. 1548.

The League of Mühlhausen essentially collapsed following Johann Friedrich’s defeat. Some holdouts in northern Germany remained, and imperial troops under the command of Eric II, Prince of Calenberg, were ordered to deal with them. He had support from the Hanseatic City of Lübeck, which contributed significantly to the imperial victory at the Battle of Adendorf, which allowed imperial authority to flourish in northern Germany once Calenberg’s army occupied Bremen. The Bruderkrieg, which had begun with a boom, now ended in a small whimper. The city of Magdeburg, one of the last remaining holdouts against the emperor, conceded to imperial demands and agreed to pay the fines that would be levied against the city. “Charles V emerged victorious from the Bruderkrieg,” one historian would write. “But the Protestant faith was a pandora’s box—twenty years past, it was far too late to push it back into the box. But Charles, often hounded and suffering losses during his time as emperor, had succeeded where his grandfather and forefathers had failed—he had secured a victory over the princes who oft stood in the way of change… giving the emperor a unique chance to secure his position—both for himself and for the House of Habsburg.” Not long after securing his victory over the Protestants, Charles called for an imperial diet to be assembled at Augsburg. Rather than returning to the Low Countries, Charles declared that he would settle in Innsbruck to await the start of the diet. Refurbishments were ordered to the Innsbruck Hofburg.

The Diet of Augsburg opened in 1548—while known in some circles as the Diet of Reforms, others derided it as the Iron Diet due to the tense atmosphere that pervaded inside it—primarily because of the emperor’s military force that controlled the diet from the outside. Aside from Charles, Maximilian and Elisabeth attended the diet, allowing Charles to meet his daughter-in-law for the first time. “His Majesty was the perfect gentleman,” one courtier wrote. “It was as if he was twenty years younger and speaking with his beloved Mary yet again.” The diet opened with routine business: Charles announced plans for Maximilian’s election as King of Romans, with the election to be held in the next year in Frankfurt. From there, Charles asked that his chancellor read his intentions for the diet and the empire: articles that would become known as the Reformatio Imperii. The first options were primarily administration: part one concerned the Reichsregiment, which was to be reformed into the Fürstenregiment, a princely council based in Brussels that would be given some distinct organizational functions for the first time. Compared to the Reichsregiment of Maximilian’s time, the Fürstenregiment was to be dominated by the emperor, who would not only serve as chairman but hold final approval for all decisions made by the Fürstenregiment. Secondly, Charles called for the Geheimer Pfennig to be permanently levied to fund the Fürstenregiment alongside the Kammerzieler, which paid for the Imperial Chamber Court and the Römermonat concerning collections for the imperial army. Like the previously mentioned tax, the imperial treasurer would handle the disbursement of the funds, with collections to be handled through the imperial circles.

Woodcut of the Diet of Augsburg, 1548—Soldiers stand prepared behind the emperor; AI Generated.

Other reforms were financial—mint regulations to help introduce economic parity between the different parts of Germany, standardize the coinage and help prevent debasement. Expansion of the Imperial postal service was ordered, with additional routes planned throughout Germany to truly connect the imperial capital in Brussels to the rest of the empire. Others were administrative—such as the reorganization of the Burgundian Imperial Circle to include the Duchy of Guelders, the County of Zutphen, and the territories of Utrecht, Groningen, Overjissel, and the County of Drenthe. The whole Burgundian inheritance and its expanded territories would be covered for the first time in one imperial circle. The Low Countries would remain attached to the Imperial Chamber Court’s jurisdiction and pay taxes equivalent to two electorates. Its war taxes would be comparable to three electorates. The final and most important reforms that Charles considered as part of his program concerned the territorial makeup within the empire, but primarily considering his own hereditary domains. The Reformatio Imperii decreed changes in the electoral challenge—Bohemia was to lose its electoral vote within the Electoral College; in exchange, the kingdom’s unique position and connection to the empire would be recognized as an imperial dependency—which came along with freedom from future imperial laws. One attendee wrote: “All waited for bated breath as the archchancellor spoke… his droning voice as he degreed that Bohemia’s vote—already in the hands of the House of Habsburg would instead pass to Burgundy…”

The most significant changes concerned the Burgundian inheritance in the Low Countries. In decreeing the transfer of the Bohemian vote to Burgundy, the Reformatio Imperii revived the use of a title already used by the Holy Roman Emperors—that of the so-called Kingdom of Burgundy, sometimes known as the Kingdom of Arles, that had existed in Provence. This kingdom would be spun off as an electorate, now to contain the Burgundian inheritance in the Low Countries—thus shifting Bohemia’s vote onto Burgundy. As part of the electoral inheritance law, this act helped further centralize the Burgundian Low Countries, ensuring they would remain together and be inherited by a single person. Another section concerned the Privilegium Maius that had allegedly made Austria an Archduchy—with Charles decreeing the children of his line would bear the title of Prince/Princess of Burgundy ahead of that of Archduke/Archduchess of Austria. Other changes concerned territorial adjustments for those of proven loyalty: Saxony, as mentioned, had passed to Severin, who had reduced the former electoral line to a tiny cluster of land. Brandenburg was allowed to absorb several districts within its domains—though not Magdeburg. Other victors were the spiritual electors and certain ecclesiastical principalities—which saw organizations of lands and territories within their favor, to make them stronger redoubts of the Catholic faith—while also increasing imperial power through the Concordat of Aix-la-Chapelle. The last statements concerned religion, and the Archchancellor was apparent as he spoke: “The emperor asks that the Protestants behave quietly and cause no trouble; he is prepared to recognize their married clergy and the laity to receive communion of both kinds. He asks that the Protestants prepare a delegation to attend the Council of Bologna as soon as possible. If reconciliation is not truly possible, then the emperor is willing to be magnanimous in his reforms.” Some could not help but genuinely wonder—what exactly did that mean?

Last edited:

mickeymouse

Donor

You CANNOT scare me like that, omg… John 😭the young king was nearly hit—a stray shot merely grazing his ear.

Wonderful chapter as always! 🤍

A German being elected king of the Romans (the Romans overthrew their last king) in Frankfurt, a German city.Charles announced plans for Maximilian’s election as King of Romans, with the election to be held in the next year in Frankfurt.

How bizarre

Augustus would be turning in his grave.

Thats the HRE for yaA German being elected king of the Romans (the Romans overthrew their last king) in Frankfurt, a German city.

How bizarre

Augustus would be turning in his grave.

Interesting, a Burgundy that becomes more centralized and the new true realm of Habsburg power as well as the Imperial reforms planting the seeds for more centralization in the future, the reaching out to the Protestants is interesting: they have been defeated military but haven't been broken and continue to spread, so the Emperor is likely just reaching out in order to avoid something like OTL 30 Years War from developing.

You go Charles! And I'm so pleased with John and his military prowess and that he and Mary has three sons now!!!

Damn. A rough end to that marriage. A shame that Charles found out about her inclinations. At least he and Renee did their duty in the bedroom. Both the Spanish line and the Austrian line seems pretty secure for nowWhen Charles ordered Renée’s own chambers searched, it was discovered that she used a secret compartment within one of her chests to hide not only Protestant tracts but letters that she had received from Jean Calvin and Philip Melanchthon, which made clear her steadfast faith. “We shall deal with this matter in due course,” Charles allegedly uttered coldly to Renée when her secret was discovered. Charles sternly ordered Renée to retire to Mechelen, where she was given the former residence of Margaret of York, the Hof van York. Renée was also forbidden to take the children: Charles retained custody of their three daughters, Anne, Adélaïde, and Michèle, as well as their two sons, Charles, and Jean. This meant an effective end to their relationship and marriage; never again would Charles and Renée live under the same roof. For now, the emperor had a greater focus than his heretic wife—he commanded none to speak of it.

John and Mary have been busy too! Henry VIII could never. We need names for the sons! Henry for the oldest ofc, but I can’t remember for the othersCharles wintered in Mainz with his nephew John. “There is naught but ice and snow everywhere we look,” John wrote in a letter to Mary. “We have been in Mainz for nearly a fortnight now, and a terrible storm rolled through overnight. The city is covered in snow, a frozen idol awaiting the warmth of spring. Continue to care for yourself and our children; I was most gladdened to hear in your last letter that little York and Somerset continue to thrive, and that Isabella has recovered from her fever.”

Once again, Henry VIII could never. And this battle will for sure be used as a PoD in this universe’s alt-history.“John II of England rode forth gloriously,” Charles Wriothesley wrote in his chronicle. “A ghost has risen from Thérouanne; the young king continued where his predecessor had started. The Hungarians failed in the first charge, and the young king was nearly hit—a stray shot merely grazing his ear. The king commanded the right flank, comprised of the finest English cavalry… a second charge against the Protestant’s weaker flank helped the king deliver victory—and the field, to the emperor. Cries of ‘For St. George! For England!’ mingled with those praising the emperor in French and German amongst sundry other tongues…”

Roar, Caesar!When news of his victory was delivered to the emperor, he had only one thing to say: “Je suis venu, j’ai vu, Dieu a vaincu.”

So, Saxony falls to a Catholic line again 150 years early! This is pretty huge, since only the Palatinate and Brandenburg are Protestant electors now. Severin will likely also be succesful in turning his realm back to Catholicism“Duke Severin of Saxony was formally granted the electoral dignity at Wittenberg Castle, and a celebratory Catholic mass was held shortly after that—perhaps the first in twenty years in Wittenberg.” Saxony’s realignment meant that one more secular elector joined the Catholic camp—leaving the Count Palatine as the sole Protestant. The fall of Wittenberg into the hands of the Catholic party was a profound shock that caused many reformers to lament.

🥹Aside from Charles, Maximilian and Elisabeth attended the diet, allowing Charles to meet his daughter-in-law for the first time. “His Majesty was the perfect gentleman,” one courtier wrote. “It was as if he was twenty years younger and speaking with his beloved Mary yet again.”

The Reformatio Imperii decreed changes in the electoral challenge—Bohemia was to lose its electoral vote within the Electoral College; in exchange, the kingdom’s unique position and connection to the empire would be recognized as an imperial dependency—which came along with freedom from future imperial laws. One attendee wrote: “All waited for bated breath as the archchancellor spoke… his droning voice as he degreed that Bohemia’s vote—already in the hands of the House of Habsburg would instead pass to Burgundy…”

Oh, Bohemia must be fuming here. They have been stripped of a lot of their Imperial influence it seems. At least, it won’t matter too much in the long term, since their kingdom would be under the Habsburgs anyways, but still… that’s gotta stingThe most significant changes concerned the Burgundian inheritance in the Low Countries. In decreeing the transfer of the Bohemian vote to Burgundy, the Reformatio Imperii revived the use of a title already used by the Holy Roman Emperors—that of the so-called Kingdom of Burgundy, sometimes known as the Kingdom of Arles, that had existed in Provence. This kingdom would be spun off as an electorate, now to contain the Burgundian inheritance in the Low Countries—thus shifting Bohemia’s vote onto Burgundy. As part of the electoral inheritance law, this act helped further centralize the Burgundian Low Countries, ensuring they would remain together and be inherited by a single person. Another section concerned the Privilegium Maius that had allegedly made Austria an Archduchy—with Charles decreeing the children of his line would bear the title of Prince/Princess of Burgundy ahead of that of Archduke/Archduchess of Austria.

So the Habsburgs will now be known as “of Burgundy”? That’s an interesting change and both signals their main powerbase (not Vienna or Prague ttl!) and is a thorn in the Eye for France. Will younger sons get parts of Austria and Bohemia here as their territories then? Since it seems they’ll get no part of the Burgundian realm.

This is a big Protestant screw! The only realms not under Catholic rule is Sweden (who might return to the fold as they almost did otl) and then some smaller Imperial nations, most prominently the Palatinate and Brandenburg. It’ll be very interesting if the Emperors can turn back the clock and heal the Church somehow (although they’d probably still have to make concessions)

Great update, Finally a win for Austria in the Bruderkreig! Clearly the only way to win is to start 300 years early!

Classy Karl giving God the glory for his victory then not dis-interring Martin Luther, true knight. Its great seeing him with Max and Elizabeth.

Transferring Bohemia's vote to Burgundy/Low Countries/"Arles" seems odd. . . why not add another, like in Hannovers case? Was it to avoid being seen as "packing" the Electorate with Habsburg votes? I think, besides the Bohemia/Burgundy vote transfer, that this is a very plausible 16th cent. Imperial Reform following a Imperial victory. I would like to see more of the HRE admin side of things, is there a perpetual diet setup any where and did Karl manage to "adjust" the Reichskammergericht court that Maximillian had foisted on him in 1495?

My 2 cents on the council would be to try and accomodate the protestants desire to have the council in Germany or maybe in Burgundy not Italy, to avoid that appearance of bias, maybe Mainz, Trier or Cologne, or maybe a lesser bishopric like maybe Trent?

Also, good job finally actually including the Burgundian inheritance into the Empire, now do so with Italy!

Classy Karl giving God the glory for his victory then not dis-interring Martin Luther, true knight. Its great seeing him with Max and Elizabeth.

Transferring Bohemia's vote to Burgundy/Low Countries/"Arles" seems odd. . . why not add another, like in Hannovers case? Was it to avoid being seen as "packing" the Electorate with Habsburg votes? I think, besides the Bohemia/Burgundy vote transfer, that this is a very plausible 16th cent. Imperial Reform following a Imperial victory. I would like to see more of the HRE admin side of things, is there a perpetual diet setup any where and did Karl manage to "adjust" the Reichskammergericht court that Maximillian had foisted on him in 1495?

My 2 cents on the council would be to try and accomodate the protestants desire to have the council in Germany or maybe in Burgundy not Italy, to avoid that appearance of bias, maybe Mainz, Trier or Cologne, or maybe a lesser bishopric like maybe Trent?

Also, good job finally actually including the Burgundian inheritance into the Empire, now do so with Italy!

Quick Question: is this supposed to be Charles' son Max or is there another Max I forgot?Maximilian’s son also pledged to provide some 13,000 troops from Bohemia if needed.

I am once again surprised that the habsburgs are basing their main court in Brussels - a court in Vienna means the emperors main focus is fighting the Turks. A court in Brussels means the emperors main focus is… what exactly? Fighting the French? Are we entirely certain Charles has given up on Ducal burgundy?

Actually, not at all. Their new status exempts them from imperial legislation, which will give them a measure of autonomy (perhaps more than they'd had previously). In terms of their religious reforms and legislation, this will essentially protect the Bohemian Hussite Church and it's reforms. Given that the kings of Bohemia in the last century or so were primarily foreign princes and sometimes emperors themselves, it'll give the kingdom some measure of autonomy. That's an even better plus when Maximilian eventually becomes emperor, since Bohemia will no doubt have a governor.Oh, Bohemia must be fuming here. They have been stripped of a lot of their Imperial influence it seems. At least, it won’t matter too much in the long term, since their kingdom would be under the Habsburgs anyways, but still… that’s gotta sting

Brandenburg is technically still Catholic too. Joachim II Hektor was a slow adapter. The Prussian / Polish invasion in the 1520s perhaps caused some reaction against the Lutherans, but it's still likely still spreading. Joachim likely won't formally abjure until Charles is dead. He has a Catholic wife, but she's an Italian princess: no large relatives there, unlike Sigismund the Old IOTL. But yes, the plan is for for Severin to reintroduce Catholicism into the cradle of the Reformation.So, Saxony falls to a Catholic line again 150 years early! This is pretty huge, since only the Palatinate and Brandenburg are Protestant electors now. Severin will likely also be succesful in turning his realm back to Catholicism

Charles is the Duke of York, Edward is the Duke of Somerset.John and Mary have been busy too! Henry VIII could never. We need names for the sons! Henry for the oldest ofc, but I can’t remember for the others

They'll likely be known as the Maison d'Autriche still, much as the Spanish like was the Casa de Austria. But like the Spanish line where their titles of Infante/Infanta of Spain held importance, the title of Prince / Princess of Burgundy will come before all the numerous other titles. This essentially resigns the title of Archduke/Archduchess into the greater titulary and it won't become widespread as it was IOTL.So the Habsburgs will now be known as “of Burgundy”? That’s an interesting change and both signals their main powerbase (not Vienna or Prague ttl!) and is a thorn in the Eye for France. Will younger sons get parts of Austria and Bohemia here as their territories then? Since it seems they’ll get no part of the Burgundian realm.

This is a big Protestant screw! The only realms not under Catholic rule is Sweden (who might return to the fold as they almost did otl) and then some smaller Imperial nations, most prominently the Palatinate and Brandenburg. It’ll be very interesting if the Emperors can turn back the clock and heal the Church somehow (although they’d probably still have to make concessions)

They will probably get pieces of the Low Countries, much as later cadets got parts of Austria. Electorates mandate primogeniture (as did Austria's status) but cadets could still be granted territories. It just wouldn't be spun off as independent entities.

I think healing the church is a step too far at this point. There certainly remain many realms within Germany that have Protestant Princes, even if the Reformation as such has mainly been confined there without spreading too far outside of it. I do have some plans for the Council of Bologna, and eventual new Pope that will decide the direction of how things are patched up or dealt with, so to speak. Even with a military victory, there will need to be some discussions on their vital differences.

The Electoral College almost always had an odd number of members, except for the brief period in the 18th century when Bavaria and the Palatinate were united, and later when Napoleon added extra electors. In the case of adding Burgundy, it would've necessitated adding another elector, plus providing them a position in the Imperial household. Not that this is out of the question later on, but given the authority and powers that the Golden Bull bestows upon electorates, IMO it makes little sense for the emperor to confer that honor when he's seeking to limit authority of the princes. There's also the fact that giving his house two votes would've likely provoked a tumult even amongst those princes and electors who are allies of the emperor... for now, better to transfer the vote. Typically when a house possessed two votes (the Wittelsbachs when they inherited the Palatinate comes to mind) they were only allowed to exercise one.Transferring Bohemia's vote to Burgundy/Low Countries/"Arles" seems odd. . . why not add another, like in Hannovers case? Was it to avoid being seen as "packing" the Electorate with Habsburg votes? I think, besides the Bohemia/Burgundy vote transfer, that this is a very plausible 16th cent. Imperial Reform following a Imperial victory. I would like to see more of the HRE admin side of things, is there a perpetual diet setup any where and did Karl manage to "adjust" the Reichskammergericht court that Maximillian had foisted on him in 1495?

At this point there is no perpetual diet: mainly because the 16th century courts are still highly iterant, so the diet moving about isn't too much trouble... though it's possible that we'll see diets more based in the areas closer to the Low Countries, Frankfurt, Aachen, ect. Augsburg and Nuremburg will likely get shafted in this arrangement.

The Reichskammergericht still exists. The Aulic Council does as well, though the Aulic Council has been moved to Brussels. It's likely there there will be further reforms to the Reichskammergericht in due time to ensure the emperor has more say over it's function and it will probably in due course end up in Brussels too.

That is a typo. Charles' son promised the troops.Quick Question: is this supposed to be Charles' son Max or is there another Max I forgot?

To be fair, Vienna isn't exactly a city that has held high importance in some time. Friedrich III lost the city to the Hungarians, and primarily reigned from Linz, while Maximilian had a fairly movable court that was based in numerous areas. He didn't stay in Vienna very often either, and his court was based in Innsbruck. Vienna was a fairly small city, of about ~20,000 people circa 1500. Combine that with Ferdinand staying in Spain, the Turkish invasion in the 1530s, the city is likely just now recovering. Charles has always been based out of Brussels ITTL, there would be no reason for him to make that change when he has a son in Bohemia watching over the frontier. With Bohemia secure and changes over the empire, it's hard to say, I think a good argument can be made for Brussels as a capital, especially with the close diplomatic connections it has to England and the remainder of Western Europe compared to being based on the Danube.I am once again surprised that the habsburgs are basing their main court in Brussels - a court in Vienna means the emperors main focus is fighting the Turks. A court in Brussels means the emperors main focus is… what exactly? Fighting the French? Are we entirely certain Charles has given up on Ducal burgundy?

Last edited:

To me such a centrally placed capital in Western Europe seems to indicate that the emperors are going for less of a defender of the frontier of Christendom vibe and more a lord of Christendom vibe.With Bohemia secure and changes over the empire, it's hard to say, I think a good argument can be made for Brussels as a capital, especially with the close diplomatic connections it has to England and the remainder of Western Europe compared to being based on the Danube.

Also it’ll be interesting to see whether the language border in the Low Countries shifts towards French, given that there’s now a centralised government which is primarily francophone in the area- conditions seem right for much of the Dutch upper and middle class to assimilate within a few centuries.

Last edited:

I could definitely see that. I think the main issue is how Maximilian's reign unfolds when he succeeds his father, given that he's the one who holds Bohemia and those pieces of Hungary.To me such a centrally placed capital in Western Europe seems to indicate that the emperors are going for less of a defender of the frontier of Christendom vibe and more a lord of Christendom vibe.

Also it’ll be interesting to see whether the language border in the Low Countries shifts towards French, given that there’s now a centralised government which is primarily francophone in the area- conditions seem right for much of the Dutch upper and middle class to assimilate within a few centuries.

French is already the language of the upper classes in the area of what is now Belgium. We also know that the Burgundian Habsburgs are primarily French language speaking and French cultured. Brussels was also a fairly Dutch speaking city at this point in time: the Francophone influences didn't come into play until the 19th-20th centuries, when they went into overdrive. I suppose there is the possibility of French to expand further, but it also relies on conditions where France remains the language of these Habsburgs. I think conditions are equally ripe for an eventual patriotic rejection in favor of Dutch or German (though they will likely know how to speak both). Dutch will certainly have some interesting effects in remaining attached to the empire: it's already got some good connections to German, and could end up further Germanized.

Chapter 39. Vivat Regina

All I can say about this chapter is that a lot of ya'll are about to be real mad at me. I dedicate this chapter to @mickeymouse who served as my very secret keeper. She knew about this chapter + outcome for several months... I had this planned about twenty chapters ago. I apologize to those I might have gassed up and misled, but hope that you remain entertained and keep reading!

Chapter 39. Vivat Regina

1545-1549; England.

“In a world of kings, I stood tall as a queen.”

— Queen Mary of England

Musical Accompaniment: Purge Me, O Lord

Henry VII and his family; c. 1505.

England, at the end of 1544, stood at the edge of greatness—the injuries of her previous conflict against France had been healed, and England had come out on top with their reconquest of Boulogne. Combined with the revision of Imperial territory, the Pale of Calais is now greatly enlarged. Mary and John stood among Europe’s most remarkable monarchs, perhaps not as their equals but as something close enough. England through the 1540s had seen various periods of Mary reigning on her own, as John dealt with problems abroad—in 1542-1543, he spent time abroad dealing with troubles in Schleswig-Holstein, while later campaigns in 1547-1548 would take him into Germany to campaign against the Protestants alongside the emperor. Because of this, Mary spent significant periods reigning without her husband. Though John would leave an indelible mark upon England, Mary would be remembered for her strength and determination as a queen regnant in a world dominated by men. “Queen Mary is often remembered for her varied life,” Évelyne Esquiros, a feminist author in the 1950s, wrote. “But it must be remembered that when she reigned, women were little better than chattel—and often without a voice. In England, she shattered that domain, and though she adhered to the gender ideals of her time and era, in others, she was a trendsetter—a woman who refused to be cowed and fought to be recognized for what she was: England’s first queen regnant. She is a true chameleon—conservative historians have often used her position as a wife and mother to view her merely through that lens, preferring to focus on John II and his reign as king. Historians of a liberal bent are beginning to discover just how often she could cloak herself in stereotypical positions as a wife and mother to advance her own power…”

John returned to England towards the end of 1544, following the end of the Italian War of 1544. After a brief visitation of the Pale of Calais, he landed in Dover, where he was greeted by his household suite—including his secretary Johan von Weze, who in 1540 had been named Bishop of Hereford. John wasted little time traveling from Dover to meet Mary at Richmond Palace, where the court was wintering. Mary’s favored residence, Greenwich, was by the 1540s undergoing significant renovations—and construction had also begun in London north of Westminster, where plans had been laid for a new royal palace alongside the Thames, known as St. Sylvester’s Palace, dedicated to Saint Sylvester, whose saint day fell upon Mary’s birthday—December 31. “The queen was most pleased to see the king’s return,” Catherine Devereaux, née Blount, wrote in a letter to her brother, Christopher Blount. “Relief and love mingled upon her façade… perhaps also with envy.” Once again, John could aid his wife in the heavy task of governance—which meant the diminishment of Mary’s position, even if only slightly. In John’s absence, there were changes to the Privy Council: Mary had replaced the Bishop of Ely as Lord Chancellor in favor of a secular lord, Ralph Neville, the Earl of Westmorland. The Bishop of London, Edmund Bonner, was named Lord Privy Seal. Elevations had been made for William Paget and Stephen Gardinier, who, alongside their positions as clerks, were given the title of Secretaries of State, with other duties.

Among new laws passed upon John’s return was the Statute of Calais, which in 1545 made provisions for the Pale of Calais to send representatives to parliament for the first time. The first representative would be nominated by the royal deputy in Calais, while the second would be chosen by the Mayor of Calais and his council. Given the nebulous situation regarding the towns of Gravelines, Dunkirk, and Boulogne, they were not included in the statute. Still, John’s interests remained primarily in military (and naval) matters. By 1545, the navy consisted of some 40 ships—and John eagerly responded to the program suggested by the Marquess of Exeter. He ordered some 30 new ships to augment England’s naval defenses, a mix of smaller vessels, with 10 new ships to be galleons—purpose-built warships. In military matters, John campaigned for the Militia Act of 1545, which would be passed by parliament. This ended England’s quasi-feudal system that had hereto been used for national defense. The Militia Act codified the position of Lord Lieutenant in England’s counties, which would take over the sheriff’s former military functions.

King John's entrance into Calais, c. 1545.

The act covered musters and the maintenance of horses and armor. No longer would soldiers or noblemen be granted indentures to raise soldiers, and the commissions of array were also rendered obsolete. The Militia Act empowered those in parishes who owned property valued at £1 per annum to be liable for militia service: they were required to own arms for training purposes. They were required to report to sporadic militia training. During the war, random drawings were to be utilized to decide who would be drawn up for militia service, with militia regiments known as Bands placed together in tercio formations. Uniforms and weaponry would be provided by the state. John’s Militia Act created a regulated force of the country’s prosperous freeholders that could serve as reservist forces quickly armed and put into the field—useful for domestic and foreign issues. The Militia Act also included a religious focus—rolls were only drawn from the official and recognized Catholic parishes and rendering the holding of arms by Protestants illegal—an underground faith that was nevertheless gaining steady popularity in urban areas. “Military matters have always reigned supreme in the king’s mind,” Baron Paget wrote in a letter to his counterpart, the Bishop of Winchester. “To him, they are of paramount concern—for the true vitality of the kingdom. It goes hand in hand with the queen’s designs—they must work in common, not in opposition.”

It was also no surprise that the king’s return meant expanding the royal family. In August 1545, Mary gave birth to her second son, Charles. Named in honor of Charles V, the young prince was christened and soon named Duke of York—though his official recognition would come when he was older. After Charles, another son quickly followed in November 1546—named Edward in honor of Edward IV, who was named Duke of Somerset. “From a sprig, a whole flower has flourished,” one English poet wrote in the 1540s in honor of the birth of the Duke of Somerset. “Leaves of white and red, melded into one—mixed with Danish blue.” For the first time since 1509, the English royal line stood secure—not only had the queen done her duty in replenishing her fragile line, but she had provided England with three sons—three young boys who would become young men in due course. Mary arranged for the royal nursery to be placed principally at Woodstock, with a secondary residence to be established at Eltham. Significant improvements were carried out at Woodstock, and both the queens paid keen attention to their children and how they were educated. Mary, the eldest royal princess, was given her household when she was six in 1541. Mary initially wished to provide the governess position to the Countess of Salisbury. Still, she declined on the grounds of ill health—suggesting that the position should be given to her daughter, Ursula Stafford. When Catherine (b. 1538) turned six, she was appointed her governess: Elizabeth Courtenay, the Marchioness of Exeter. Still, the education of Mary and John’s eldest son, Henry, was paramount. Henry formally passed out of the care of women shortly after his sixth birthday when the Count of Surrey was appointed governor of his household. Henry’s first tutors were Owen Oglethorpe, President of Magdalene College, along with an Italian tutor, Jacopo Bonfadio.

Though the Prince of Wales was growing older, a more paramount concern once more drew John out of the kingdom. “I am preparing to undertake a campaign that has been in my designs since that vile monk first opposed me,” Charles V wrote in a letter to John in 1545. “I am asking for your aid and assistance—and hoping that you, as the Most Pious King of England, will aid me in excising this disease that has too long rotted my dominions.” Compared to distaste for an imperial alliance against the French, this idea appealed to John—to prove his worth as a Catholic monarch against the Protestant heresies that still festered in Europe. “The queen has lately been greatly agitated,” Frances Howard, the Countess of Surrey, wrote to the Countess of Arundel—Anne Fitzalan. “None can truly provide a balm in these situations except for you. She does not say it but longs for your return to court.” While Mary did not disagree with the emperor’s request or John’s desire to aid him, she sought that England have some material gain—even for a religious undertaking. “I know of your wishes best, as you know mine best,” a letter from Mary to John began—one of the few letters between the two preserved. “There is no doubt that I fear for your person… but we both know that we cannot solely render our aid on the cause of our faith or familial connections. Too often, my beloved mother sought to do the same, and you know where it has gotten us… as my lord husband and sovereign of this kingdom, you are fit to do as you please; I merely ask that you consider the funding of this undertaking—ask that in return, the emperor make good on some of his promises.” While John’s reply was not preserved, reports of the Exchequer from the period note a payment of £50,000 into the treasury from the emperor—the first installment of his £300,000 debt which he owed.

Palace of Saint Sylvester, 19th c. Watercolor; AI Generated.

Though John received assurances from the emperor that he would be more than willing to ensure that the English troops would have their needed supplies, John would still need the necessary funding to pay his men throughout the campaign. “In his plans for the campaign, there is no doubt that the king perhaps contributed in some form to the financial issues that England would endure in the 1550s,” one economic historian would write. “Others were structural problems that other European monarchies dealt with during this period: obsolete financial systems that could not bring in or generate the income needed to maintain an early modern state.” In this, John was pretty limited in what he could do to raise funds: taxation would require parliamentary support, while the selling of crown lands would require the support of the queen—an idea that she might not endorse. John decided that he would need to raise the funds on his own, turning to members of his household for assistance. They proposed that the king go around the queen and seek help directly from the royal mint. The so-called Mühlhausen Debasement, named for the League of Mühlhausen, showed the issues of two co-sovereigns with equal power. In 1545, John issued a secret decree to the Royal Mint, calling for a temporary debasement of coinage in both weight and fineness—with the saved bullion for John’s eventual campaign in Germany. “The debasement showed what could happen when the two co-monarchs with equal authority had conflicting views,” one historian wrote of the co-monarchy of Mary and John. “They governed well, but their views were not always in alignment. Indeed, they often conflicted. Just as Mary aligned England with the emperor in 1543 over her husband’s objections, John sought to raise funding for his eventual campaign in Germany—and perhaps future campaigns, right under the queen’s nose.” For now, John ordered that the debased coinage be stored at the Jewel Tower in Westminster Palace and not put into active circulation. The crafty trick earned John a profit of £50,000—which he ordered his household treasurer to put towards his future military expenses.

John’s campaign in Germany would last a little over a year—from 1546 to June 1547. By autumn, John and his troops returned to England relatively unscathed—of the 10,000 men that had accompanied him, some 8500 returned to England—more lost to disease and sickness than in battle. “The campaigning in Germany had only invigorated His Majesty to seek further changes to England’s military system,” Baron Paget wrote in a letter to the Bishop of Hereford. “He desires to go beyond the militia act and formally institute a true royal army—not an ad-hoc force raised for campaigns, but a standing army available for any cause, domestic or foreign. A great expense, no doubt—but he hopes that might bring the idea up to the queen first… he is aware of her fondness for you and hopes it may soften her heart towards the idea…”