I definitely agree it won't be a cake walk and the Spanish are still likely to support their cousins in what manner they can but I think it would be slightly easier for France as Spain still has their own issues to worry about outside of always helping out their Austrian cousins, so France can make some better inroads into the Netherlands hereI don't think the separation of the two branches necessarily means that France is just going to have easy pickings of the Netherlands. Their foreign policy is likely to still be dictated by fears of Habsburg encirclement, and the two branches are likely to continue to work together in areas of mutual interest, of which containing France will probably be of a primary interest. A strong France is a threat to Spain just as much as it is to the Empire. There's a long storied history of Franco-Spanish conflict, long before the Italian Wars, and that rivalry is certain to remain. I think the ATL Spanish kings will certainly have a different policy from the OTL Spanish Habsburgs, who saw themselves as the defenders of Catholicism, but you could see the ATL Spanish kings cloak their policy in similar religious views.

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Anno Obumbratio: A 16th Century Alternate History

- Thread starter DrakeRlugia

- Start date

Threadmarks

View all 53 threadmarks

Reader mode

Reader mode

Recent threadmarks

Chapter 40. Memoriae Sacrum Addenum: Additional AI Portraits / Images Chapter 41. Rogues of Italy Chapter 42. The Imperial Division Chapter 43. The Council of Lucerne Chapter 44. The Fürstenkrieg — The Italian War of 1555-1562; Part 1. Chapter 45. An English Rose (With Thorns) Addendum: Dynastic Trees (Updated to 1559)

Addendum: Dynastic Trees

Here are the family trees, as requested. I plan on doing more, there are some royal families I haven't touched, such as the Vasas, and perhaps the Rurikids. I also would like to do the major German dynasties at some point (Hohenzollern of Brandenburg, Wittelsbach, Wettin) as well as the major Italian dynasties, and the French Bourbons. I suppose there's a few spoilers in here, but nothing major that won't be covered in due time. This isn't totally complete or updated for the current period, but for the most part will show everyone what is going on.

Anno Obumbratio — Dynastic Trees

Dynastic Trees from the 16th Century

Abbreviations Guide:

M. = Married; Multiple marriages equal m1, m2, m3 depending on number of marriages.

B. = Betrothed

Ann. = Annulled

Div. = Divorced

Ilg. = Illegitimate issue

Major Royal Houses—

House of Tudor (England):

House of Lorraine (Lorraine):

Anno Obumbratio — Dynastic Trees

Dynastic Trees from the 16th Century

Abbreviations Guide:

M. = Married; Multiple marriages equal m1, m2, m3 depending on number of marriages.

B. = Betrothed

Ann. = Annulled

Div. = Divorced

Ilg. = Illegitimate issue

Major Royal Houses—

House of Tudor (England):

- Henry VII, King of England (1457 – 1509) m. Elizabeth of York (1466 – 1503); Had Issue.

- Arthur, Prince of Wales (1486 – 1502); m. Catherine of Aragon (1485 –); No Issue.

- Margaret (1489 —); m. James IV, King of Scots (1473 – 1513)

- Henry VIII, King of England (1491 – 1513) m. Catherine of Aragon(1485 –); Had Issue.

- Mary, Queen of England (1513 —) b. John of Denmark (1518 –)

- Mary (1496 –); m. Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor (1500 —); Had Issue.

- Maximilian I, Holy Roman Emperor (1459 – 1519) m1. Mary of Burgundy, Duchess of Burgundy (1457 – 1482); Had Issue. m2. Anne of Brittany, Duchess of Brittany (1477 – 1514) ann. 1492; m3. Bianca Maria Sforza(1472 – 1510); No Issue.

- Philip I, King of Castile & Duke of Burgundy (1478 – 1506) m. Joanna of Castile, Queen of Castile & Aragon (1479 –); Had Issue.

- Eleanor (1498 —) m1. Louis XII, King of France (1462 – 1515); No Issue. m2. John of Portugal, Crown Prince of Portugal (1502 –)

- Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor (1500 –) m. Mary of England(1496 – ); Had Issue.

- Philip (1517 – 1521); Died Young.

- Isabella (1521 –)

- Maria (1522 –)

- Elisabeth (1524); Stillborn.

- Maximilian (1527 –)

- [Ilg.] Joanna (1522 –) with Johanna Maria van der Gheynst.

- Isabella (1501 –) m. Christian II, King of Denmark & Norway (1481 –)

- Ferdinand, Prince of Asturias (1503 –) m. Isabella of Portugal (1503 –)

- Mary (1505 –) m. Louis II of Hungary, King of Bohemia & Hungary (1506 –)

- Catherine (1507 –) m. Charles III of Savoy, Duke of Savoy (1486 –)

- Margaret, Governor of the Low Countries (1480 —) m1. John of Aragon, Prince of Asturias & Girona (1478 – 1497); No Issue. m2. Philibert II, Duke of Savoy (1480 – 1504); No Issue.

- Louis XII, King of France (1462 – 1515) m1. Joan of France (1464 – 1505); ann. 1498—No Issue; m2. Anne of Brittany, Duchess of Brittany (1477 – 1514); Had Issue. m3. Eleanor of Austria(1498 —); No Issue.

- Claude, Duchess of Brittany (1499 – 1522); m. Francis, King of France (1494 —); Had Issue.

- Renée (1510 —)

- Charles of Orléans, Count of Angoulême (1459 – 1496); m. Louise of Savoy(1476 —); Had Issue.

- Marguerite (1492 —); m. Charles IV, Duke of Alençon (1489 –); No Issue.

- François, King of France (1494 –) m1. Claude of France, Duchess of Brittany (1499 – 1522); Had Issue. m2. Beatrice of Portugal(1504 –)

- Louise (1515 –)

- Charlotte (1516 –)

- Madeleine (1517 – 1518); Died Young.

- Anne (1518 –)

- François (1519 –)

- Charles (1520 – 1529); Died Young.

- Victoire (1521 –)

- Louis (1522 –)

- [Ilg.] Elisabeth (1527 –) with Anne de Boullan.

- René of Alençon, Duke of Alençon (1454 – 1492) m1. Marguerite of Harcourt (14?? – 14??); No Issue. m2. Marguerite of Lorraine (1463 – 1521); Had Issue.

- M2. Charles IV, Duke of Alençon (1489 –) m. Marguerite of Angoulême (1492 –); No Issue.

- M2. Françoise (1490 –) m1. François of Orléans, Duke of Longueville (1478 – 1512); m2. Charles of Bourbon, Count of Vendôme (1489 –)

- M2. Anne (1492 –) m. William IX Palaeologus, Marquis of Montferrat (1486 – 1518)

- Catherine of Navarre, Queen of Navarre (1468 – 1517) m. Jean III, King of Navarre(1469 – 1516); Had Issue.

- Anne (1492 –)

- Magdalena (1494 – 1504); Died Young.

- Catherine, Abbess of the Trinity at Caen (1495 –); Unmarried.

- Joan (1496); Died Young.

- Quiteria, Abbess of Montvilliers (1499 –); Unmarried.

- Andrew Phoebus (1501 – 1503); Died Young.

- Henri II, King of Navarre (1503 –)

- Buenaventura (1505 – 1510); Died Young.

- Martin (1506 – 1512); Died Young.

- François (1508 – 1512); Died Young.

- Charles (1510 –)

- Isabella (1513 –)

- Manuel, King of Portugal (1469 – 1521) m1. Isabella of Aragon, Princess of Asturias (1470 – 1498); Had Issue. m2. Maria of Aragon (1500 – 1517); Had Issue.

- M1. Miguel, Prince of Asturias and Portugal (1498 – 1500); Died Young.

- M2. João, King of Portugal (1502 –); m. Eleanor of Austria (1498 –)

- Maria (1521 –)

- Carlos (1522 –)

- Afonso (1524 – 1526); Died Young.

- Isabel (1526); Died Young.

- Manuel (1527); Died Young.

- Joanna (1528 – 1533); Died Young.

- Beatriz (1530 –)

- M2. Isabel (1503 –) m. Ferdinand of Spain, Prince of Asturias (1503 –)

- M2. Beatriz (1504 –) m. François of France (1494 –)

- M2. Luís, Duke of Beja (1506 –)

- M2. Fernando, Duke of Guarda (1507 –)

- M2. Afonso, Bishop of Guarda (1509 –)

- M2. Enrique (1512 –)

- M2. Maria (1513); Died Young.

- M2. Duarte (1515 –)

- M2. António (1516); Died Young.

- Christian I, King of Denmark (1426 – 1481) m. Dorothea of Brandenburg (1430 – 1495); Had Issue.

- John, King of Denmark(1455 – 1513)

- Christian II, King of Denmark (1481 –) m. Isabella of Austria (1501 – 1526); Had Issue.

- John (1518 –) b. Mary Tudor, Queen of England (1513 –)

- Philip (1519); Died Young.

- Maximilian (1519); Died Young.

- Dorothea (1520 –)

- Christina (1521 –)

- Christian II, King of Denmark (1481 –) m. Isabella of Austria (1501 – 1526); Had Issue.

- Margaret (1456 – 1486) m. James III of Scotland, King of Scots (1452 – 1488)

- Frederick I, King of Denmark (1471 – 1533) m1. Anna of Brandenburg (1487 – 1514); Had Issue. m2. Sophia of Pomerania (1498 –); Had Issue.

- M1. Christian (1503 –)

- M1. Dorothea (1504 –)

- M2. Elizabeth (1520 –)

- M2. John (1523 –)

- M2. Adolf (1525 – 1527); Died Young.

- M2. Anna (1527 –)

- John, King of Denmark(1455 – 1513)

- Vladislaus II, King of Bohemia & Hungary (1456 – 1516) m1. Barbara of Brandenburg (1464 – 1515); div. 1490 ann. 1500; No Issue. m2. Beatrice of Naples (1457 – 1507); ann. 1500; No Issue. m3. Anne of Foix-Candale(1484 – 1506); Had Issue.

- M3. Anne (1503 –) m. John Zápolya, King of Hungary (1487 –)

- M3. Louis II, King of Bohemia & Hungary (1506 – 1526) m. Mary of Austria (1505 –); Had Issue.

- Elizabeth, Queen of Bohemia (1525 –)

- Sigismund, King of Poland & Grand Duke of Lithuania (1467 –) m. Barbara Zápolya (1495 –); Had Issue.

- Hedwig (1513 –)

- Sigismund (1515 –)

- Alexander (1516 – )

- Anna (1520 –)

- Sophia (1523 –)

- Casimir (1527); Died Young.

House of Lorraine (Lorraine):

- René II, Duke of Lorraine (1451 – 1508); m. Philippa of Guelders(1464 –); Had Issue.

- Antoine, Duke of Lorraine (1489 – 1515) m. Renée of Bourbon (1494 –); No Issue.

- Claude (1496 – 1515) m. Antoinette of Bourbon(1494 –); Had Issue.

- Marie (1515 –)

- Jean III, Duke of Lorraine (1498 –) m. Maria of Montferrat (1508 –); Had Issue.

- François (1525 –)

- Anne (1526); Died Young.

- Philippe (1528 –)

- Louis, Count of Guise (1500 –)

- François, Count of Vaudémont (1506 –)

Last edited:

Not sure yet! I considered a marriage to Francis after the death of Claude, but considering his bevy of children, there's little need for it. The Valois succession to France and Brittany is secure in his three sons. She may marry into Italy as IOTL, or she could perhaps marry the King of Navarre. The Duke of Alençon is still alive, so if he doesn't die within the next few years, Margaret of Angouleme won't be a suitable bride for Henri II. There was already a pretty big age gap: she was 34 when they married.What are you going to do with Reena of France in this timeline?

Chapter 18. Clash of the Leagues – The War of the League of Valenciennes

Sorry for the delay, everyone. Had another doozy of a chapter.

This one is quite long as well, but hopefully everyone enjoys reading it. Things take some twists as we head into the 1530s, and we say hello to some new characters, and goodbye to some as well.

Chapter 18. Clash of the Leagues – The War of the League of Valenciennes

1526-1530; France, Germany, Hungary, Italy & Poland.

“Love! I who feel you don’t know you at all.

And so can only win the loser’s prize.”

— Ausiàs March, Voyage of Love or Death

Music Accompaniment: Danse Alta

Cambrai Madonna, c. 1350.

The Treaty of Rambouillet which had ended the Italian War of 1521 to 1526 had imposed humiliating terms upon Emperor Charles V—the cession of territories in Italy, Navarre, and within the Low Countries—along with a crippling ransom. Though the emperor had endured the battering of his pride, he was able to end his imprisonment in France with his agreement to the terms—along with handing over his eldest daughter and several nobles as hostages. The holdover ceremony was held at Cambrai with great pomp—with the King of France and Holy Roman Emperor sharing a warm embrace, with François speaking first to the emperor: “Cousin, remember all that I have done for you—as my friend and ally. Let peace reign between our two realms. You have only to sign the terms once more.” Charles V was solemn in his response: “Indeed, my cousin—I shall never forget what you have done.” Empress Mary attended the holdover ceremony, with Princess Isabella in tow—the small, delicate princess dressed in a gown of white etched with golden fleur-de-lys—with a cloak of silver. “Do well and be good, always.” The empress said to her young daughter—attempting to hold back her tears. “Treat the King of France as you would your father; and be kind to the Dauphin. Never forget—you are the descendant of the greatest of kings, that of England and Spain—and of the Caesars, as well. The greatest of blood flows in your veins—be aware of your dignity and never forget it.” Embraced and blessed by the emperor, Princess Isabella was soon embraced by King François—before being handed off to the Governess of the Children of France, Madame de Brissac. This was followed by the handover of the selected nobles.

Charles arrived in Brussels the day after the holdover—where he was greeted by his aunt, Margaret of Austria—as well as his primary councilors: Chancellor Gattinara, Francisco de los Cobos, and Nicolas Perrenot de Grenvelle, among others. It was upon his return that Charles was acquainted with what had transpired in his absence—most importantly the fait accompli regarding Spain and Ferdinand being named as Prince of Asturias. The news shocked the emperor, who denounced the Cortes as a nest of vipers—yet the emperor knew that this was a decision that he would not be able to undo without significant trouble. France remained a vehement enemy—and Charles understood he would need the support of Spain, even if that kingdom seemed to be rapidly slipping from his grasp. One of the emperor’s first letters following his release was written to Ferdinand: “It is your heroic service which helped secure my release in those terrible hours of my French confinement—it is a deed that deserves to be recognized, and there is certainly no greater reward for you than to be named my heir in Spain. As the Cortes has already rendered this gift, I recognize it and confirm it without reservations… you shall continue to be my representative in Spain and govern the kingdom in my absence, which I expect to be for a long time yet.” Rather than fight against the tide in a losing battle, Charles preferred to recognize where things stood; better for the Spanish to rejoice in this choice and be more willing to fight against their common foe than for the emperor to fight against them and endure further issues. This helped to further solidify Ferdinand’s grip on the royal government in Spain—to the benefit of the prince’s political allies, such as the Archbishop of Santiago, Juan Pardo de Tavera.

Ferdinand essentially gained a free hand in dealing with the government of Spain following the emperor’s confirmation of his position as Prince of Asturias. As the emperor retreated from direct decision-making in Spain, the task largely fell to Ferdinand. One of the Prince’s first reforms concerned the Council of Castile—formed in the time of Queen Isabella as an administrative and judicial organ, it had become a hated symbol of the crown’s arbitrary policies during Charles’ earliest years. Ferdinand named the Archbishop of Santiago as president of the council—with the council to focus solely on administrative matters; Judicial issues would instead be handled by an expanded judiciary, centered around the audencias. Castile had two such courts, in Valladolid and Granada—with a new audencia created in Zaragosa to handle judicial cases in Aragon. Further reforms narrowed the purview of the Council of Castile—with the foundation of a Council of Finances to handle the business of the treasury, while the Council of the Indies was created to govern Spain’s burgeoning territories in the Americas and East Indies. It was also at this time that Ferdinand was able to begin to embark on his foreign policy—albeit one still rather tied to the whims and needs of his eldest brother, the emperor. Having heeded the demands of the Cortes to seek out a more beneficial marriage, Ferdinand had terminated his engagement to Anna Jagiellon and now looked towards the kingdom that might be more likely to provide Spain with its next consort: Portugal. “The king and I both look forward to seeing you at Olivença—it has been so long, and how things have changed!” Eleanor of Austria wrote in a letter to her brother ahead of a planned meeting of the Spanish and Portuguese courts at Olivença. “The king’s sisters shall be coming as well, of course—Isabella and Beatriz. They are beautiful—and I believe you will enjoy the company of both.” The courts met at Olivença in May of 1526—the Archbishop of Santiago meeting with his Portuguese counterparts to discuss differences between the two kingdoms—primarily their competing influence in East Asia, centered around the Moluccas Islands. Ferdinand got along well with both Portuguese princesses. “He is a true Spaniard—decorous and courteous, with a dignity that cannot be matched,” one Portuguese courtier wrote in his memoirs. “Last night, he danced with both princesses—yet his eyes always seemed entirely focused upon Princess Isabella—and her eyes upon him.” Was it love at first sight? Perhaps. But it was clear to all involved, most especially Queen Eleanor—that the Prince of Asturias was taken with Princess Isabella, and most assuredly would make her his wife.

The Infantas Isabella & Beatriz of Portugal.

The meeting at Olivença brought about the Treaty of Olivença—in which Spain ceded their interests in the Moluccas to Portugal and recognized that the Spice Islands lay within Portugal’s zone of interest per the Treaty of Torsedillas. The terms of Ferdinand and Isabella’s marriage were also included within the treaty—it was agreed that Isabella’s dowry would be set at 900,000 Cruzados, which would help with Spain’s financial issues stemming from the payment of the emperor’s ransom. Ferdinand wasted little time in obtaining the necessary papal dispensation for the pair to marry—which Pope Pius IV readily provided. Arrangements for the marriage carried throughout 1526, and in January of 1527, Isabella crossed the border into Spain with her suite—comprising of several Portuguese noblemen, including a young man named Ruy Gomez de Silva, who would remain attached in her service for several years. Isabella would be greeted at the border by the Duke of Calabria, the Archbishop of Toledo, and the Duke of Béjar—where she would be escorted to Valladolid. Ferdinand and Isabella would be married on St. Valentine’s Day of 1527. The day was one of great celebration and revelry—celebrated by the Spaniards as the dawn of a new age—a new generation of Catholic Monarchs, a new Ferdinand and Isabella that would one day be their king and queen—and would in due time provide a new line of kings and princes who would bring Spain to the newest heights of glory. Spain’s wishes could be confirmed in 1528—when Isabella gave birth to a healthy son—named Fernando Alonso, in honor of his grandfather, Ferdinand of Aragon—as well as the ancient Kings of Castile, who typically bore the name Alfonso.

Charles dealt with his issues upon his release from France. The Treaty of Rambouillet hung over his head; not only was he required to cede the territory that comprised Isabella’s dowry within four weeks of his release. He was also required to ratify the treaty once more—all while obtaining the agreement of the Cortes of Castile and the Council of Mechelen. Charles had been counseled during his imprisonment that the treaty would hold no weight once he was free—and his council concurred. “This treaty is not worth the parchment it is written upon,” Chancellor Gattinara was recorded as saying in one tenuous council meeting—before setting the treaty ablaze in a nearby fireplace. “It is more kindling than a diplomatic agreement!” To the surprise of no one, Emperor Charles V repudiated the Treaty of Rambouillet in April 1526. Soon after, the treaty was roundly rejected by both the Castilian Cortes and the Council of Mechelen—neither body would countenance the dismemberment of their realms because of the whims of the French. “He is a bastard and a liar,” François exclaimed when he heard of the Holy Roman Emperor’s duplicity. “I have bested him once—and I shall best him again!” While Princess Isabella would remain cossetted in the care of the Governess of the Children of France, the noble hostages handed over by the emperor were transferred to the Bastille, placed into dank cells, and threatened daily with execution for their sovereign’s treachery.

As tensions grew between Charles V and François once more, trouble loomed in Italy, where French troops under Sieur de La Palice had succeeded in capturing great portions of the Kingdom of Naples—including not only the capital of Naples, but Salerno, Potenza, and even Bari—where the Duchess of Bari, Bona Sforza, proved a helpful ally to the French. Bona Sforza’s fortunes were further attached to France when she wed Philippe of Savoy in 1526, brother to Louise of Savoy and a suitor from the Duchess of Bari’s youth. The Duchess of Bari was active in providing aid to the French army in Naples; Sieur de La Palice was granted a loan of 150,000 ducats at ten percent interest—with the loan to be guaranteed by custom duties from the ports of Otranto and Brindisi. The Duchess also readily provided recruits and supplies from her domains—while encouraging neighboring lords and landowners to do the same. Spanish resistance in the Kingdom of Naples was headed by Alfonso d’Ávalos was centered in the southern leg of the kingdom around Reggio, where d’Ávalos received support from the Viceroy of Sicily, the Duke of Monteleone. It was little surprise that the French success in Naples had aroused the unease of the Italian princes who in the aftermath of Lodi sought accommodations with France. Pope Pius IV—hailing from the Colonna family who had a storied association with the Ghibellines, had begun to tire of his alliance with King François and sent secret envoys to treat with the emperor. The Pope made clear his intimations: he was prepared to break away from the French and support a restoration of the Sforza in Milan, in exchange for the concession of Parma and Piacenza. Further support came from other Italian princes, such as the Duke of Modena and Ferrara, and the Marquis of Mantua. Envoys from these states negotiated with the emperor at Valenciennes in May of 1526, bringing about the League of Valenciennes—an offensive alliance aimed at curbing French ambitions in Europe.

François was not idle as the emperor allied against him. He maintained his allies in Italy—primarily the Republic of Florence and Venice, and sought out his alliances abroad, with French envoys being sent to Krakow to treat with the King of Poland. Poland had long wearied of Habsburg ambitions in Central Europe, and the Queen of Poland, Barbara Zápolya—sister to John Zápolya—was known for her open disdain for the Habsburgs. The Treaty of Wawel signed in the autumn of 1526 created not only a Franco-Polish alliance aimed against Emperor Charles V but also arranged for François’ second son, the Duke of Orléans to be betrothed to Princess Anna of Poland. Sigismund also promised to undertake a military expedition against the Holy Roman Emperor in Germany. It was during this period that France attempted to forge its friendly relations with Portugal, perhaps in the hope of weening King João III away from his pro-Habsburg policy. While King João had little interest in arranging an alliance with the French, the Treaty of São Jorge was negotiated in December of 1526—providing for a marriage between François and João’s younger sister, Princess Beatriz—with Beatriz to bring a dowry of some 600,000 Cruzados to France. “Though there was some unease in some quarters regarding Infanta Beatriz’s proposed marriage to King François,” an anonymous courtier wrote in his memoirs. “The Infanta herself was overjoyed—a brilliant and ambitious young woman, she saw great glories in her future position as Queen of France.”

François’ new bride would arrive in France in the summer of 1527—with Beatriz and her trousseau arriving at the port of La Rochelle. She was met at Poitiers by her future Chamberlain, François de la Rouchefoucald, along with members of her French household. The official meeting between Beatriz and King François was at Châtellerault, with one courtier writing: “The Infanta Béatrice was la belle—beautiful! Her eyes were shaped like almonds, with plump lips and a Romanesque nose… every inch a princess, with dignity natural only to the royalty of Iberia. His Majesty was more than joyous when he set eyes upon her. She was certainly prettier than the late queen; more well-read, and well-spoken as well—the king’s equal, rather than his subordinate.” François and Beatriz were married shortly thereafter at Châtellerault; though some believed the new marriage might break the hold in which the king’s maîtresse-en-titre held over him, it was not to be. In September of 1526, Anne had given the king an illegitimate daughter, named Elisabeth, after her mother. Anne’s position became solidified—she was even named one of Beatriz’s ladies-in-waiting. When Beatriz made her official entrance into Paris in 1528, François was seen watching the ceremony with Anne de Boullan by his side—showing himself and his mistress to the Parisian public for several hours, to their acclaim and applause. Afterward, it was said that the queen fumed with rage—she not only quarreled with King François but became so sick from her anger that she was forced to take to her bed, suffering a miscarriage. A Venetian diplomat wrote in the aftermath that: “The Queen shortly before Michaelmas delivered a still-born child of about five months, a daughter. The queen grieves the loss and blames the king; the king in turn blames the queen for her theatrics and has chided her to obey him in all things in the future. His Majesty has not spoken to the queen since—nor has he deigned to visit her bed. His time is spent with his belle anglaise.”

The War of the League of Valenciennes, as it became known, broke out in July of 1526 when imperial troops under Georg von Frundsburg invaded Lombardy. With the majority of the Armée d’Italie campaigning in Naples, imperial troops were able to capture Pavia and establish themselves in Lombardy with ease. At the Battle of Rogoredo, the French garrison of Milan under Teodoro Trivulzi clashed with the imperial army, suffering a grave loss that forced Trivulzi to abandon Milan—heading eastward into Venetian territory. In Spain, troops under the Duke of Najéra battled against the remnants of the Franco-Navarrese expedition which had seen its holdings dwindle; any goodwill that the French had earned in the years previously had quickly evaporated due to the heavy-handed policies of André de Foix—who found his star in rapid descent following the replacement of his sister as the king’s mistress. The absence of Henri II, who remained comfortably in France also did not inspire confidence. Pamplona was subjected to heavy artillery fire under siege, with the fight coming to a head at the Battle of Villava, where Spanish troops proved victorious under Najéra’s command—with André de Foix killed in battle. Despite these first victories, the war was far from over—the German Princes remained constrained from rendering much aid to the emperor, as they dealt with the aftermath of the peasant revolts which had rocked the empire throughout 1524 and 1525.

Throughout the winter of 1526, King Sigismund of Poland convened the Polish Sejm to obtain financing for the royal army. Taxes were introduced in the royal lands to pay for the coming campaign season, and the Sejm also authorized the king to mobilize the szlatcha into providing forces for the Polish army through the pospolite ruszenie. Sigismund also called upon his newest vassal, Albert—the former Grand Master of the Teutonic Order, now Duke of Prussia—who agreed to provide military support to the King of Poland. The Polish army crossed the frontiers of the empire in the spring of 1527—the city of Küstrin was occupied, and the Neumark and parts of Pomerania were ravaged harshly by Polish troops. The Duke of Prussia was especially noted for his fierceness, with a local burgher writing: “The Preußen were vicious, their zeal focused on the Romanish churches and monasteries… the charterhouse at Frankfurt an der Oder was brutally set ablaze by Duke Albert, the House of God reduced to cinders and ash as the Polish soldiers looked away…” Joachim, the Elector of Brandenburg was shocked by the Polish intrusion into his domains—he called up his levies to prevent the Poles from pressing further into domains—writing helplessly to the emperor in search of his aid. The Diet of Wetzlar was held in 1527—which Charles V attended, in conjunction with the Papal Nuncio, Lorenzo Campeggio. The continued growth of the reform movement—along with the failures of the Edict of Worms meant that new faith continued to spread, and some princes, such as Philip of Hesse and Elector John of Saxony confirmed their faith for the first time. The Diet pressed not only for the authorization of the Imperial Army to deal with the Polish invasion but also addressed the growing religious crisis: while prominent Protestant princes attempted to bring about a suspension of the Edict of Worms, a majority vote of the princes instead reconfirmed the edict: “Heresy and rebellion shall be put down,” the chancellor read aloud to the assembled diet. “And the Edict of Worms shall be enforced under the penalty of the imperial ban. All decisions and discussions regarding the religious question and future settlement shall be postponed until a General Council can be called.” Though the Diet of Wetzlar closed without issues, it created a bridge between the Catholics and Protestants that would not be easily resolved—Protestant opposition to the emperor’s policies would continue to grow.

Charles III, Duke of Bourbon and Constable of France.

Aside from the imperial campaign in Italy, the winter of 1526 had seen the emperor also put together an army in the Low Countries, which was placed under the command of Heinrich V of Brunswick-Wolfenbüttel, the Duke of Brunswick-Lüneburg. François was not restless throughout the winter either—he spent the early months of 1527 drawing together an army in Paris under the command of his brother-in-law, the Duke of Alençon—a major snub to the Duke of Bourbon, who had requested command of the army as Constable of France. Even the Duke of Alençon dying from a burst belly shortly after taking command of the army did not see the army go to Bourbon. The growing tension between François and the Duke of Bourbon represented a final breach in their relationship. Bourbon retired to his estates near Moulins—where he wrote a scathing letter to one of his close associates: “I can bear no further attacks from His Majesty; his esteem for me has slackened, and he no longer favors me as he had on the onset of his reign. He is dominated by that bitch he calls a mother—his favor is now saved for those who are most in awe of him—not by those who can do the job best. So long as they both live, I shall never know any rest.” Little surprise that this unfortunate memorandum fell directly into the hands of the king—who ordered that Bourbon be arrested for plotting the king’s death and be kept closely confined at Moulins. Rather than submit to such indignities, the Duke of Bourbon instead chose to flee. Aided by a close circle of sympathizers, the Duke of Bourbon arrived untouched in Besançon in Franch-Comté, where he penned a letter to the emperor: “I look to you, and only you as a solution to my current issues. I offer my sword in your service.” Such news was favorably received by Charles V—who granted him an army of some 10,000—comprised of Burgundian infantry and knights, and some 5000 German landsknechts. While the French army fought back imperial forces under the Duke of Brunswick-Lüneburg at the Battle of Crépy, the Duke of Bourbon was ordered to march into Italy to support the imperial forces under Georg von Frundsburg—now in full control of Milan and pressing south towards the Republic of Florence.

1528 saw a further shift in alliances. Charles V attempted—to little avail—to persuade his aunt, Catherine of Aragon, to reaffirm her alliance with Spain and the Empire. Though the Queen Regent of England remained sympathetic to the cause of her nephew, she was constrained by political issues—not her conscience. Archbishop William Warham, Lord Chancellor for over two decades had been replaced by Bishop John Fisher, renowned for his attacks against Luther. Under Fisher, Parliament was pressed to pass the Heresy Act of 1527, which strengthened existing heresy laws passed by Richard II and Henry V by allowing sentences to be passed against Lutherans—including burnings. Fisher was vehement against an offensive alliance aimed at France—counseling that England’s treasury remained in a poor state—while reminding the queen firmly that her nephew had yet to repay a single farthing from the various loans that he had taken out from England previously. Though Catherine greatly desired to aid her nephew, she was forced to temporize—and maintained England’s neutrality in the growing conflict. In Italy, the imperial army, now supported by the Duke of Bourbon, made the march upon Florence, which agitated the anti-Medicean factions. They revolted against Cardinal Giulio de Medici, forcing both the cardinal and young Lorenzo de Medici to seek refuge in Romagna. The Medici ouster did not radically alter the politics of Florence; the newly declared Republic was hostile against the approaching imperial army, and the gates were locked as they approached. If Florence was to be dealt with, the city would need to be taken.

In Naples, the remaining troops under Alfonso d’Ávalos surrendered following a fierce fight at the Battle of Luzzi, where despite their loss, the Spanish succeeded in inflicting significant losses among the Armée d’Italie. The former Viceroy of Naples would be confined at Castel Nuovo, held under strict guard. “The once grand viceroy was treated as a vanquished dog—he was paraded into Naples in chains,” wrote an anonymous French officer in a letter to his wife. “The Neapolitan miserabili jeered at the Spaniard—pelting him with stones and rotten eggs. Louis, the Count of Guise sat at the head of procession, even ahead of the Sieur de La Palice… almost like a conqueror… cheered on as a young hero…” While the defeat of the remnants of the Spanish army in Naples gave Sieur de La Palice needed breath, the French troops remained in a dire situation, trapped in Naples following Pope Pius IV’s realignment with the empire. Leaving a garrison of troops in Naples under the Viscount of Lautrec, the French army was prepared to go north—not only to deal with the Papacy but to provide relief to their Florentine allies. Charles V gained further allies when Charles III, the Duke of Savoy signed onto the League of Valenciennes through the Treaty of Chieri. Aside from an alignment with the emperor, Charles V also promised territorial concessions—offering the duke the Lordship of Asti, as a dowry for the duke’s wife, who happened to be the emperor’s sister, Catherine of Austria. Savoyard troops as well as mercenary troops under Fabrizio Maramaldo began the Siege of Asti, pounding the French holding in Piedmont with excessive artillery fire. In Rome, Pope Pius IV was struck down in May of 1527 with an attack of the flux. Forced to take to his bed, the papal administration fell into confusion, with intrigues breaking out between the rival factions. On May 30th of 1527—Pope Pius IV died, leaving the Papacy vacant and throwing the situation into the Papal States into further turmoil.

Calling of the Apostles, Domenico Ghirlandaio, c. 1483.

The Papal Conclave of 1527 was one of the most contentious in papal history—held amid open conflict between the King of France and the Holy Roman Emperor, both of whom hoped to influence the outcome of the election. Divisions among the College of Cardinals had also increased during Pius IV’s tenure, resulting in the creation of three disparate factions: the pro-French, the pro-Imperial, and the pro-Italians. The Conclave opened towards the end of June; neither the pro-French nor the pro-Imperial factions possessed the necessary numbers for a candidate of their liking to prevail. Little surprise that two compromise candidates appeared among the papabile—Cardinal Alessandro Farnese, the last cardinal named by Alexander VI, and Cardinal Giovanni Piccolomini, nephew of Pope Pius III. On July 10th, 1527, Cardinal Giovanni Piccolomini commanded the votes needed to become Pope—taking the name Pius V in honor of his uncle. Pope Pius V did not drastically step away from the foreign policy favored by his predecessor—and in the meantime, maintained his alliance with the emperor through the League of Valenciennes.

Bourbon’s defection to the imperial side led to François naming the Duke of Bourbon as a traitor, and his lands and holdings were confiscated. The duke’s son—François, the Count of Clermont was allowed to maintain the bulk of the Bourbon holdings, which he had inherited from his mother. Clermont was placed into the care of Louise of Savoy as a royal ward. As the situation continued to unfold in Italy, with the Duke of Savoy leading the siege of Asti, François prepared for a fresh campaign in Italy in 1529—wanting to send further troops into the peninsula to aid his ailing armies in southern Italy. The situation in Navarre continued to be advantageous to the Spanish troops under the Duke of Najéra; with the end of the Siege of Pamplona in 1527, the French had lost control of Upper Navarre—with the remnants of the expedition fleeing beyond the Pyrenees to Pau. Ferdinand ordered the summoning of the Cortes of Navarre at Olite, where their obeisance to Charles V as King of Navarre was reconfirmed. Ferdinand was prepared to deal with an even hand with the Navarrese—while some of the worst offenders who had supported the French invasion were sentenced to death, many more were able to escape relatively unscathed—with punishments ranging from the seizure of lands and estates to heavy fines. Ferdinand also confirmed Navarre’s traditional fueros—in a simplified law set known as the Fuero Reducido. Despite this, François was still eager to expand his alliances abroad; in 1528, he concluded the Treaty of Fontainebleau with King John Zápolya in Hungary. The new Hungarian king was promised financial and other material support in dealing with the Ottomans; in return, Zápolya was to undertake an invasion of Austria and provide Hungarian troops for the French in Italy.

The war rapidly began to heat up outside the environs of Italy. Hungary, flush with French money soon began to raid across the border into Austria in 1529—while King John Zápolya sent his main army into Moravia in Bohemia—he attempted to spook the Bohemian nobility who had in the year previously elected the Princess Elizabeth—daughter and heir of Louis II of Hungary—as Queen of Bohemia, with her mother, the Queen Dowager of Hungary as her regent. Jan Pernstejn commanded the Bohemian army to victory at the Battle of Eibenschütz against Zápolya’s army—ensuring that Elizabeth would remain Queen of Bohemia. Charles V provided his sister not only with troops from the Imperial Army—but urged her to counterattack as soon as possible. Within the empire, growing unease among the Protestant princes led to the formation of the League of Zwickau—a defensive league spearheaded by the Landgrave of Hesse and the Elector of Saxony. Though the league would falter within the year due to a lack of religious and military influence, it would help contribute provisions and funds to both Bohemia as well as to Pomerania—helping contribute to the defense at the Siege of Stettin. “The Poles had pressed through the Neumark like butter,” a German writer of the period wrote. “But squabbles between the Duke of Prussia and the Szlachta commanders meant that there could be no agreement. The Duke of Prussia chose to raid Brandenburg from the Neumark, while the Polish army attempted to take Stettin—a complete failure, as the port remained well provisioned from the sea. The Polish army melted away like dust—its numbers reduced by disease and sickness.” Following the failure at Stettin, the disintegrated Polish army would abandon its positions and return to Polish territory. The Duke of Prussia remained encamped within the Neumark for several more months—the Battle of Lebus proved indecisive for both Brandenburg and Prussia—the Duke of Prussia agreed to vacate the Neumark after extracting a payment of some 15,000 ducats from the Elector; the city of Schwiebus was also forced to offer up some 5000 ducats to avoid being sacked by the Prussian troops as well—a sum that was raised by the burghers of the city.

Siege of Florence, 1529.

France now had raised two armies alongside the Armée d’Italie—an army stationed in northern France, which had dealt with the incursions of the emperor’s Burgundian troops, where they clashed along the border, where the French laid siege to Arras in their invasion of Artois. The imperial troops in the Netherlands had not only to contend with the French but also with Charles II, the Duke of Guelders, who was invited into Utrecht by the Bishop, Henry of the Palatinate. The citizens of Overjissel requested imperial support against the Duke of Guelders, which the emperor granted—on the provision that they should recognize him as their lord, which was agreed upon. A detachment of troops under Georg Schenck von Toutenburg easily chased the Guelders troops out of Utrecht, where they had overstayed their welcome; while the order was restored, the emperor demanded that the whole of the Bishopric of Utrecht’s temporal territories—Utrecht as well as Overjissel should be handed over to him. The Bishop of Utrecht swore fealty to Charles V, and Pius V would sanction the transfer of territory, which ended Utrecht’s position as a temporal bishopric. The troops of the Duchy of Guelders were led by Maarten van Rossum, who in the aftermath of the fall of Utrecht led a daring raid upon The Hague, which ended in it being sacked. Toutenburg in return ravaged the southern portions of Guelders, laying waste to Tiel and Wageningen. Charles II of Guelders was forced to accept peace through the Treaty of Dorecht—the emperor acknowledged Charles II’s control over Guelders, Groningen, and Drente, but as imperial fiefdoms. Duke Charles II, having no legitimate heir of his own, was also forced to accept Charles V as his heir.

The southern French army was built up around Lyons and was soon ordered to invade the Duchy of Savoy—under the command of François of Bourbon, Count of Saint-Pol. Georges Boullan, brother to the king’s mistress led the cavalry in a stunning charge at the Battle of Fossano, ensuring victory over the minuscule Savoyard army. France soon received reinforcements in Savoy from the Marquis of Saluzzo as well as the Marquis of Montferrat—both French allies who provided much-needed munitions and supplies. France soon occupied the whole Duchy of Savoy—lifting the siege at Asti and forcing Charles III to flee into exile—where he and his wife would find refuge in Brussels. Imperial troops fared better at Florence, where the Siege of Florence ended with imperial troops occupying the city. Bourbon ordered the hanging of Francesco Ferruccio, commander of the republican troops—while the imperial army indulged in an orgy of violence, theft, and murder—perhaps urged on by financial issues that plagued the army. Charles V was pleased with the news coming from Florence—and wrote to Cardinal Giulio de Medici: “Florence has fallen, and so have the republican partisans. They have been dealt with; I know that which you desire for your grandnephew; should you desire to cease clinging to French skirts, I would be willing to return Florence into the hands of the Medici family—for a suitable ransom.”

Pius V was also forced to face the first difficult situation in his pontificate. While he had maintained his alliance with the emperor, he had not been active in aiding the League of Valenciennes. With the French Armee d’Italie converging on Rome in 1529, Pius V knew that he stood alone. Imperial forces occupying Florence were still too far away—and would likely be forced into open battle against the French army that had smashed into Savoy. Pius V had inherited a pitiful treasury, and his predecessor had even resorted to the creation of four cardinals to come up with funds to pay for Rome’s defense. As the French army approached from the south, it numbered some 22,000 men. As the French army approached, Pius V decided that his safest bet was to send envoys to meet with the French commander. Sieur de La Palice met with the papal envoys outside the city walls—with French artillery already set up for a possible barrage should negotiations fare poorly. La Palice was willing to negotiate openly with the new pontiff, knowing that his political views were starkly different from the pro-Ghibelline Pius IV. France’s main terms for Pius V were simple: a separate peace between the Pope and France, with the French army allowed open access through the Papal States—as well as rights for French vessels at the Papal port of Civitavecchia. The Pope would also agree to pay some 400,000 ducats to the French army. A bolder demand came from a retinue of Neapolitan nobles, headed by Giovanni Caracciolo, the Prince of Melfi, and Andrea Acquavita, the Duke of Atri: they demanded that Pius V grant the throne of Naples—not to François of France, but to Louis, the Count of Guise—brother to the Duke of Lorraine, who family had inherited the Angevin claim to Naples. When Pius V received the terms offered, he was nearly bowed over: “Our Eternal City has been given another reprieve.” Rather than subject Rome to artillery fire and a fight it could not possibly win, he decided that the best possible situation was for the Papacy to accept the terms offered by the French.

The French entrance into Rome was arranged for April 15th of 1529—and much like the French entry into Rome in 1494, it did not occur without incident, and emotions ran high among the Roman populace. “The French entered the city through the Porta Latina, proceeding onto the Via Appia.” an anonymous writer of the period wrote. “The Roman populace watched from their rooftops and balconies, their faces sullen and withdrawn. The great artillery wagons were lumbered slowly through the street—eventually being set up in the Capitoline Hill, as well as in the Vatican—turned against the city in an ominous threat. A deputation of senators and princes met the French commanders—less as equals, and more as slaves. Pro-Imperial cardinals and nobles were targeted—their palazzo looted, and treasures loaded into the French baggage train.” Discontent among the Roman militia simmered and was harshly put down by the French troops. It was then that Pius V had invited a nest of vipers into his capital—though the French were passing through, they would pass through as conquerors, not as friends. Both the Sieur de La Palice and the Count of Guise were received lavishly at the Apostolic Palace, where they received an audience with Pius V. Both men were allowed to kiss the papal ring, and Louis, the Count of Guise was especially honored—given all the trappings and reception due a king—even a king who might not have been crowned yet. Discussions were held regarding the terms discussed by both parties—culminating in the signing of the Treaty of Frascati. This marked an end to Papal participation in the League of Valenciennes and ensured that the Armée d’Italie would have free passage through the Papal States. It was after the signing of the treaty that Pius V met with the Neapolitan deputation in person—they once more reiterated their request directly to the Pope. “We ask to be freed from Spanish bondage, and from the dominion of King Charles,” said the elderly Duke of Atri. “I have labored since the time of King Ferrante to be free from Aragonese tyranny; we who beseech you are devoted Guelphs and partisans of the House of Anjou. The crown by rights belongs to Louis, the Count of Guise—he is an heir to the heritage of King René, and rightful king of Naples and Sicily.” Pius V had his reservations—and asked to meet briefly with his curia before rendering a decision the next morning. The Curia had their reservations—but agreed that given that French troops had effectively occupied Rome, it would be better to accede to the request of the Neapolitan baronage, which seemed to have official backing from the Sieur de La Palice. Should the French continue to hold in Italy, Pius V would gain a powerful friend; if the French faltered and the emperor became the dominant force in Italy, it would be easy enough to reverse course—it was agreed that the Pope should swear secretly before signing any treaty concerning Naples that he had been forced to act under duress.

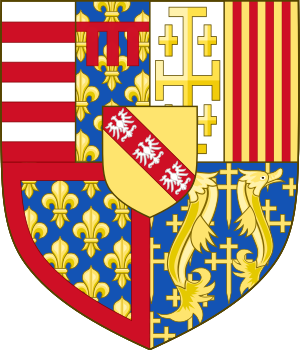

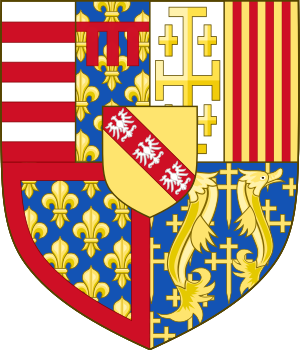

Coat of Arms used by Jean, Duke of Lorraine.

They would be adopted by Louis IV of Naples, as well.

The next morning, Pius V agreed that the crown of Naples and Sicily should pass from Emperor Charles V into the hands of Louis of Lorraine. The Treaty of Benevento, as it would called, was signed between Louis, the Count of Guise—who became known as Louis IV of Naples[2], the Pope, and the Sieur de La Palice on behalf of France. Louis IV was recognized as the King of Naples and Sicily—with France promising to aid in the eventual conquest of Sicily, which remained in Spanish hands. It also laid out what would be due to the Pope through the Chinèa—the annual tribute paid by the Kings of Naples to the Pope, with Louis IV agreeing that the tribute would be paid yearly on June 29th—including not only the traditional white horse but 10,000 ducats. The Treaty also laid out terms for Naples's relationship with France—Louis IV agreed that French troops would be garrisoned in several places within the kingdom, such as Aquila, Bari, Gaeta, Naples, Taranto, and Reggio, among others—with costs to be borne by Naples. French vessels would also be granted access to Neapolitan ports and a perpetual alliance between France and Naples would also be signed. Louis IV would be crowned King of Naples by Pius V in St. Peters Basilica—a sumptuous ceremony attended by the crème of the Roman nobility, as well as the Neapolitan deputation. When news reached François of Louis’ coronation, he was the first to pen him a letter of support: “I salute you—no longer as a cousin, but as a brother. Remember all that France has done for you—and will continue to do for the glory of Naples and your crown.”

Now, the War of the League of Valenciennes entered its last stages. Though Emperor Charles V was outraged by the betrayal of Pius V and the handover of Naples, his main army in Italy remained constrained facing down the French army that had invaded Savoy. The emperor was also facing severe financial issues—the payment of his ransom had weighed heavily upon his finances, and the imperial troops in Italy had not been paid in several months—leading to simmering discontent. Spain, too, suffered from financial problems—with Ferdinand being forced to earmark significant sums to pay for his armies. His primary focus had been on Navarre—and he spent significant sums maintaining the Duke of Nájera’s army, as well as subsidizing the Viceroy of Sicily. Ferdinand’s focus remained on Spain’s primary fronts—and not upon the other areas where the emperor needed assistance. The lack of battles after Florence had sapped the imperial army of discipline, and payment for the mercenary troops had fallen into significant arrears. While Georg von Frundsburg attempted to restore order in the Italian army, his inability to do so struck the old commander so terribly that he suffered a stroke—he sickened and died soon after. The Imperial camp was made at Carpiano, where the final battle of the war would occur—the Battle of Carpiano, named not as a skirmish between the French and the Emperor, but because of an internal breakdown of the Imperial Army, with the mercenary troops turning against their captains. With the death of Frundsburg, command fell to the Duke of Bourbon, who was felled in battle by his men—allegedly shot at point-blank range. With the revolt of the mercenaries and common troops, the imperial army melted away, and when the news reached the emperor, it was said that he wept, for he knew that the war was then lost.

Charles soon reached out to François to offer terms of peace, and it was arranged for the peace conference to be held in Longwy in the Duchy of Lorraine. Though François and Charles were both in attendance, negotiations were primarily conducted through the two most important women in both men’s lives—Louise of Savoy for François, and Empress Mary for Charles V—both men refusing to be in a room with one another. Though the Imperial army had suffered grave losses in Italy, the Burgundian troops had held their own against the French—denying François a victory in an area that was sorely needed. The Treaty of Longwy became known as the Paix des Madames or Madam’s Peace. It was agreed that the Dauphin’s betrothal to Princess Isabella would remain—though François was forced to agree that the emperor should be allowed to maintain Artois and Franche-Comté until the date of their marriage—to be agreed upon during later discussions. It was also agreed that Princess Isabella would remain in French custody, while the emperor be allowed to redeem the nobles who had been taken as French hostages for a sum of one million écus. More crushing were the terms in Italy: not only was France to retain Milan, where authority had all but collapsed following the army revolt at Carpiano, but Charles V was forced to accept the loss of Naples—with Louis IV recognized as king. In turn, the Spanish holdings in Sicily were confirmed, with Louis IV waiving all rights to the Sicilian throne: once more dividing the two territories into separate kingdoms. Separate articles concerned Florence—which was to be returned to Cardinal Giulio de Medici as regent for Lorenzo III. Aside from accepting a French garrison in Florence, it was agreed that the Republic of Florence should be abolished; in its place, Pope Pius V agreed that young Lorenzo should be the first Duke of Florence—effectively transforming the republic into a hereditary monarchy. This represented the high point of French influence in Italy since the time of Charles VIII—for the first time since the earliest days of the Italian Wars, France now held influence throughout the peninsula, from Milan down to Naples—now headed by a monarch from a French leaning dynasty who had, in essence, chained his new kingdom to France’s whims. While it would remain to be seen how things would hold, François had come through victorious, and the emperor further battered.

Death of the Virgin, Caravaggio.

The Treaty of Longwy was finalized in August. At a final banquet that celebrated the peace treaty, Empress Mary reported feeling ill—and begged leave from her husband to retire, who readily granted it. “Her Majesty was not herself that last night,” Anne de Croÿ, Empress Mary’s primary lady-in-waiting wrote in a private letter. “She had always been quite delicate, exhausted by the trials she had endured… she collapsed in her suite, and the imperial doctors were summoned to her bedside, where she was feverish and nearly incoherent. The doctors gave her a pill called archanum with opium, pearls, and musk, as well as a draught of nightshade and hebane to calm her nerves and allow her to rest. Yet for all the medicine the doctor provided, it did not help. The empress suffered a terrible fit, coughing up blood and unable to speak. It was agreed that the emperor should be called, as well as the priests…” Torn away from the banquet, Charles V was summoned to his wife’s bedside—where the household almoner was already performing last rites for the empress. Charles took Mary’s hand—its thread of life becoming rapidly weaker. “I know that I have not been the most perfect husband,” the emperor was recorded as saying. “But know that you have always been a perfect wife—and one could ask for none better than you. I ask that you forgive my transgressions.” Though some said the empress was already unconscious when the emperor arrived, others said that she heard every word, and spoke her own. “For your transgressions, you are forgiven—and have always been forgiven,” Mary was recorded as saying. “I thank Your Majesty for his kindness, but I know I have given you troubles and piques that I know well. It pains me to leave you and our children—but I am weary, and it is my time to go. Ensure that Isabella reaches her destiny as Queen of France; be kind to Marie—she is quiet and dutiful and will need your attention… ensure that she has a brilliant match. And Maximilian—my little prince; he is your heir, and he must live! Take the greatest care of him and educate him well—he must be as great an emperor as his father and forefathers. And be kind to your nephew, John—I have done better for him than I could any son of mine… he will be the next King of England. I ask that you keep peace with my homeland and ensure this marriage comes to pass. Do not grieve my lord, for I am okay—I can rest easy, knowing that I will see our dearest Philip once again. For my sake, remember—you are still young, and need further issue. I beseech you—remarry as soon as you can.”

On August 11th, 1529—Empress Mary passed from this world. Her last words rang hollow to the emperor—though their marriage had not been passionate, he had been fond of her: she had proved herself a diligent consort and had served during his troubles where no one else might have. How could he dare to think of remarriage when her corpse was not yet cold? Yet when news reached the French camp, the cogs of King François were already beginning to turn. How else could he bind the emperor closer to his person and ensure that peace might endure? “It is simple: Madame Renée,” an anonymous French courtier wrote. “The king’s mother suggested that the emperor might be bound closer to France through a marriage to Princess Renée, the sole remaining daughter of Louis XII; with the betrothal to be contingent upon the signing of the Treaty of Longwy—with an adequate time before the marriage.”

When Empress Mary’s body was cut open to remove her heart, a large black lump was discovered deep within the tissue of her breast. When the surgeons pierced it, a dark liquid spewed forth—noxious and vile. Her heart was in terrible condition, blackened in several spots, as was her liver. While some whispered of poison, others saw a weary woman, run down by a decade of misery and sickness who had simply collapsed. Empress Mary’s funeral cortege was magnificent—and the empress herself would be laid to rest in the Cathedral of Saint Michael and Saint Gudula; her will, aside from releasing the funds to assist in paying for her tomb and effigy, also allocated funds to pay for a cenotaph dedicated to Prince Philip. Her will left most of her estate to her husband, Charles V. Bequests were made not only to her daughters and her son but to Prince John of Denmark, who was to receive 15,000 ducats, while Queen Mary of England was granted several pieces of jewelry which Mary had brought with her from England. A small sum of 5000 ducats was also granted to Charles Brandon, who had been made the Viscount of Strêye, to discharge debts he had incurred in service to the Empress. Mary’s will also decreed that her heart should be buried separately from her body in the Church of the Lady, where both Charles the Bold and Mary the Rich had been laid to rest.

[1] Clement VII granted Naples and Sicily to Louis IOTL, during the League of Cognac. Due to the situation here, I don’t find such an offer from the baronage to be farfetched.

[2] Louis III was the brother of René d’Anjou—he was never effectively king, but recognized as such for a brief period in 1419; given the Angevin heritage, I figure Louis will take IV as his numeral.

This one is quite long as well, but hopefully everyone enjoys reading it. Things take some twists as we head into the 1530s, and we say hello to some new characters, and goodbye to some as well.

Chapter 18. Clash of the Leagues – The War of the League of Valenciennes

1526-1530; France, Germany, Hungary, Italy & Poland.

“Love! I who feel you don’t know you at all.

And so can only win the loser’s prize.”

— Ausiàs March, Voyage of Love or Death

Music Accompaniment: Danse Alta

Cambrai Madonna, c. 1350.

The Treaty of Rambouillet which had ended the Italian War of 1521 to 1526 had imposed humiliating terms upon Emperor Charles V—the cession of territories in Italy, Navarre, and within the Low Countries—along with a crippling ransom. Though the emperor had endured the battering of his pride, he was able to end his imprisonment in France with his agreement to the terms—along with handing over his eldest daughter and several nobles as hostages. The holdover ceremony was held at Cambrai with great pomp—with the King of France and Holy Roman Emperor sharing a warm embrace, with François speaking first to the emperor: “Cousin, remember all that I have done for you—as my friend and ally. Let peace reign between our two realms. You have only to sign the terms once more.” Charles V was solemn in his response: “Indeed, my cousin—I shall never forget what you have done.” Empress Mary attended the holdover ceremony, with Princess Isabella in tow—the small, delicate princess dressed in a gown of white etched with golden fleur-de-lys—with a cloak of silver. “Do well and be good, always.” The empress said to her young daughter—attempting to hold back her tears. “Treat the King of France as you would your father; and be kind to the Dauphin. Never forget—you are the descendant of the greatest of kings, that of England and Spain—and of the Caesars, as well. The greatest of blood flows in your veins—be aware of your dignity and never forget it.” Embraced and blessed by the emperor, Princess Isabella was soon embraced by King François—before being handed off to the Governess of the Children of France, Madame de Brissac. This was followed by the handover of the selected nobles.

Charles arrived in Brussels the day after the holdover—where he was greeted by his aunt, Margaret of Austria—as well as his primary councilors: Chancellor Gattinara, Francisco de los Cobos, and Nicolas Perrenot de Grenvelle, among others. It was upon his return that Charles was acquainted with what had transpired in his absence—most importantly the fait accompli regarding Spain and Ferdinand being named as Prince of Asturias. The news shocked the emperor, who denounced the Cortes as a nest of vipers—yet the emperor knew that this was a decision that he would not be able to undo without significant trouble. France remained a vehement enemy—and Charles understood he would need the support of Spain, even if that kingdom seemed to be rapidly slipping from his grasp. One of the emperor’s first letters following his release was written to Ferdinand: “It is your heroic service which helped secure my release in those terrible hours of my French confinement—it is a deed that deserves to be recognized, and there is certainly no greater reward for you than to be named my heir in Spain. As the Cortes has already rendered this gift, I recognize it and confirm it without reservations… you shall continue to be my representative in Spain and govern the kingdom in my absence, which I expect to be for a long time yet.” Rather than fight against the tide in a losing battle, Charles preferred to recognize where things stood; better for the Spanish to rejoice in this choice and be more willing to fight against their common foe than for the emperor to fight against them and endure further issues. This helped to further solidify Ferdinand’s grip on the royal government in Spain—to the benefit of the prince’s political allies, such as the Archbishop of Santiago, Juan Pardo de Tavera.

Ferdinand essentially gained a free hand in dealing with the government of Spain following the emperor’s confirmation of his position as Prince of Asturias. As the emperor retreated from direct decision-making in Spain, the task largely fell to Ferdinand. One of the Prince’s first reforms concerned the Council of Castile—formed in the time of Queen Isabella as an administrative and judicial organ, it had become a hated symbol of the crown’s arbitrary policies during Charles’ earliest years. Ferdinand named the Archbishop of Santiago as president of the council—with the council to focus solely on administrative matters; Judicial issues would instead be handled by an expanded judiciary, centered around the audencias. Castile had two such courts, in Valladolid and Granada—with a new audencia created in Zaragosa to handle judicial cases in Aragon. Further reforms narrowed the purview of the Council of Castile—with the foundation of a Council of Finances to handle the business of the treasury, while the Council of the Indies was created to govern Spain’s burgeoning territories in the Americas and East Indies. It was also at this time that Ferdinand was able to begin to embark on his foreign policy—albeit one still rather tied to the whims and needs of his eldest brother, the emperor. Having heeded the demands of the Cortes to seek out a more beneficial marriage, Ferdinand had terminated his engagement to Anna Jagiellon and now looked towards the kingdom that might be more likely to provide Spain with its next consort: Portugal. “The king and I both look forward to seeing you at Olivença—it has been so long, and how things have changed!” Eleanor of Austria wrote in a letter to her brother ahead of a planned meeting of the Spanish and Portuguese courts at Olivença. “The king’s sisters shall be coming as well, of course—Isabella and Beatriz. They are beautiful—and I believe you will enjoy the company of both.” The courts met at Olivença in May of 1526—the Archbishop of Santiago meeting with his Portuguese counterparts to discuss differences between the two kingdoms—primarily their competing influence in East Asia, centered around the Moluccas Islands. Ferdinand got along well with both Portuguese princesses. “He is a true Spaniard—decorous and courteous, with a dignity that cannot be matched,” one Portuguese courtier wrote in his memoirs. “Last night, he danced with both princesses—yet his eyes always seemed entirely focused upon Princess Isabella—and her eyes upon him.” Was it love at first sight? Perhaps. But it was clear to all involved, most especially Queen Eleanor—that the Prince of Asturias was taken with Princess Isabella, and most assuredly would make her his wife.

The Infantas Isabella & Beatriz of Portugal.

The meeting at Olivença brought about the Treaty of Olivença—in which Spain ceded their interests in the Moluccas to Portugal and recognized that the Spice Islands lay within Portugal’s zone of interest per the Treaty of Torsedillas. The terms of Ferdinand and Isabella’s marriage were also included within the treaty—it was agreed that Isabella’s dowry would be set at 900,000 Cruzados, which would help with Spain’s financial issues stemming from the payment of the emperor’s ransom. Ferdinand wasted little time in obtaining the necessary papal dispensation for the pair to marry—which Pope Pius IV readily provided. Arrangements for the marriage carried throughout 1526, and in January of 1527, Isabella crossed the border into Spain with her suite—comprising of several Portuguese noblemen, including a young man named Ruy Gomez de Silva, who would remain attached in her service for several years. Isabella would be greeted at the border by the Duke of Calabria, the Archbishop of Toledo, and the Duke of Béjar—where she would be escorted to Valladolid. Ferdinand and Isabella would be married on St. Valentine’s Day of 1527. The day was one of great celebration and revelry—celebrated by the Spaniards as the dawn of a new age—a new generation of Catholic Monarchs, a new Ferdinand and Isabella that would one day be their king and queen—and would in due time provide a new line of kings and princes who would bring Spain to the newest heights of glory. Spain’s wishes could be confirmed in 1528—when Isabella gave birth to a healthy son—named Fernando Alonso, in honor of his grandfather, Ferdinand of Aragon—as well as the ancient Kings of Castile, who typically bore the name Alfonso.

Charles dealt with his issues upon his release from France. The Treaty of Rambouillet hung over his head; not only was he required to cede the territory that comprised Isabella’s dowry within four weeks of his release. He was also required to ratify the treaty once more—all while obtaining the agreement of the Cortes of Castile and the Council of Mechelen. Charles had been counseled during his imprisonment that the treaty would hold no weight once he was free—and his council concurred. “This treaty is not worth the parchment it is written upon,” Chancellor Gattinara was recorded as saying in one tenuous council meeting—before setting the treaty ablaze in a nearby fireplace. “It is more kindling than a diplomatic agreement!” To the surprise of no one, Emperor Charles V repudiated the Treaty of Rambouillet in April 1526. Soon after, the treaty was roundly rejected by both the Castilian Cortes and the Council of Mechelen—neither body would countenance the dismemberment of their realms because of the whims of the French. “He is a bastard and a liar,” François exclaimed when he heard of the Holy Roman Emperor’s duplicity. “I have bested him once—and I shall best him again!” While Princess Isabella would remain cossetted in the care of the Governess of the Children of France, the noble hostages handed over by the emperor were transferred to the Bastille, placed into dank cells, and threatened daily with execution for their sovereign’s treachery.

As tensions grew between Charles V and François once more, trouble loomed in Italy, where French troops under Sieur de La Palice had succeeded in capturing great portions of the Kingdom of Naples—including not only the capital of Naples, but Salerno, Potenza, and even Bari—where the Duchess of Bari, Bona Sforza, proved a helpful ally to the French. Bona Sforza’s fortunes were further attached to France when she wed Philippe of Savoy in 1526, brother to Louise of Savoy and a suitor from the Duchess of Bari’s youth. The Duchess of Bari was active in providing aid to the French army in Naples; Sieur de La Palice was granted a loan of 150,000 ducats at ten percent interest—with the loan to be guaranteed by custom duties from the ports of Otranto and Brindisi. The Duchess also readily provided recruits and supplies from her domains—while encouraging neighboring lords and landowners to do the same. Spanish resistance in the Kingdom of Naples was headed by Alfonso d’Ávalos was centered in the southern leg of the kingdom around Reggio, where d’Ávalos received support from the Viceroy of Sicily, the Duke of Monteleone. It was little surprise that the French success in Naples had aroused the unease of the Italian princes who in the aftermath of Lodi sought accommodations with France. Pope Pius IV—hailing from the Colonna family who had a storied association with the Ghibellines, had begun to tire of his alliance with King François and sent secret envoys to treat with the emperor. The Pope made clear his intimations: he was prepared to break away from the French and support a restoration of the Sforza in Milan, in exchange for the concession of Parma and Piacenza. Further support came from other Italian princes, such as the Duke of Modena and Ferrara, and the Marquis of Mantua. Envoys from these states negotiated with the emperor at Valenciennes in May of 1526, bringing about the League of Valenciennes—an offensive alliance aimed at curbing French ambitions in Europe.

François was not idle as the emperor allied against him. He maintained his allies in Italy—primarily the Republic of Florence and Venice, and sought out his alliances abroad, with French envoys being sent to Krakow to treat with the King of Poland. Poland had long wearied of Habsburg ambitions in Central Europe, and the Queen of Poland, Barbara Zápolya—sister to John Zápolya—was known for her open disdain for the Habsburgs. The Treaty of Wawel signed in the autumn of 1526 created not only a Franco-Polish alliance aimed against Emperor Charles V but also arranged for François’ second son, the Duke of Orléans to be betrothed to Princess Anna of Poland. Sigismund also promised to undertake a military expedition against the Holy Roman Emperor in Germany. It was during this period that France attempted to forge its friendly relations with Portugal, perhaps in the hope of weening King João III away from his pro-Habsburg policy. While King João had little interest in arranging an alliance with the French, the Treaty of São Jorge was negotiated in December of 1526—providing for a marriage between François and João’s younger sister, Princess Beatriz—with Beatriz to bring a dowry of some 600,000 Cruzados to France. “Though there was some unease in some quarters regarding Infanta Beatriz’s proposed marriage to King François,” an anonymous courtier wrote in his memoirs. “The Infanta herself was overjoyed—a brilliant and ambitious young woman, she saw great glories in her future position as Queen of France.”

François’ new bride would arrive in France in the summer of 1527—with Beatriz and her trousseau arriving at the port of La Rochelle. She was met at Poitiers by her future Chamberlain, François de la Rouchefoucald, along with members of her French household. The official meeting between Beatriz and King François was at Châtellerault, with one courtier writing: “The Infanta Béatrice was la belle—beautiful! Her eyes were shaped like almonds, with plump lips and a Romanesque nose… every inch a princess, with dignity natural only to the royalty of Iberia. His Majesty was more than joyous when he set eyes upon her. She was certainly prettier than the late queen; more well-read, and well-spoken as well—the king’s equal, rather than his subordinate.” François and Beatriz were married shortly thereafter at Châtellerault; though some believed the new marriage might break the hold in which the king’s maîtresse-en-titre held over him, it was not to be. In September of 1526, Anne had given the king an illegitimate daughter, named Elisabeth, after her mother. Anne’s position became solidified—she was even named one of Beatriz’s ladies-in-waiting. When Beatriz made her official entrance into Paris in 1528, François was seen watching the ceremony with Anne de Boullan by his side—showing himself and his mistress to the Parisian public for several hours, to their acclaim and applause. Afterward, it was said that the queen fumed with rage—she not only quarreled with King François but became so sick from her anger that she was forced to take to her bed, suffering a miscarriage. A Venetian diplomat wrote in the aftermath that: “The Queen shortly before Michaelmas delivered a still-born child of about five months, a daughter. The queen grieves the loss and blames the king; the king in turn blames the queen for her theatrics and has chided her to obey him in all things in the future. His Majesty has not spoken to the queen since—nor has he deigned to visit her bed. His time is spent with his belle anglaise.”

The War of the League of Valenciennes, as it became known, broke out in July of 1526 when imperial troops under Georg von Frundsburg invaded Lombardy. With the majority of the Armée d’Italie campaigning in Naples, imperial troops were able to capture Pavia and establish themselves in Lombardy with ease. At the Battle of Rogoredo, the French garrison of Milan under Teodoro Trivulzi clashed with the imperial army, suffering a grave loss that forced Trivulzi to abandon Milan—heading eastward into Venetian territory. In Spain, troops under the Duke of Najéra battled against the remnants of the Franco-Navarrese expedition which had seen its holdings dwindle; any goodwill that the French had earned in the years previously had quickly evaporated due to the heavy-handed policies of André de Foix—who found his star in rapid descent following the replacement of his sister as the king’s mistress. The absence of Henri II, who remained comfortably in France also did not inspire confidence. Pamplona was subjected to heavy artillery fire under siege, with the fight coming to a head at the Battle of Villava, where Spanish troops proved victorious under Najéra’s command—with André de Foix killed in battle. Despite these first victories, the war was far from over—the German Princes remained constrained from rendering much aid to the emperor, as they dealt with the aftermath of the peasant revolts which had rocked the empire throughout 1524 and 1525.